Perhaps you've come across them in Freedom Park along the Little Sugar Creek Greenway — sinuous, ropey berms, studded with native plants and almost hidden from view in a wet, shaded area. They look like the remains of something from another culture or time, but they are relatively new. And by next year, they will probably be gone.

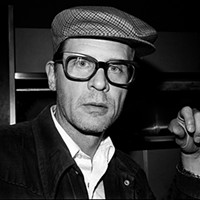

This is the work of Daniel McCormick, an ecological artist who combines the aesthetics of land art and a mission to reclaim threatened watersheds via sculptures that restore eroded stream banks and recharge aquifers. McCormick is now working with McColl Center for Visual Art to implement an environmental artist-in-residence program that mentors others artists to take their work outdoors in ways that enrich both nature and community.

Trained as an architect at UC Berkeley, McCormick also studied ecology and biology as an undergraduate. For his innovative projects, he relies on an array of experts, including Parks & Recreation staffers, stormwater hydrologists, and conservationists. Grant writing and other administrative muscle comes from his partner, artist Mary O'Brien.

When McCormick came to McColl in fall 2009 for a three-month artist's residency, he intended to create a watershed sculpture for the Little Sugar Creek Greenway and then return home to Marin County, Calif. But his project generated so much community engagement — an outpouring of corporate and nonprofit foundation support, plus legions of volunteers eager to get wet and dirty in the name of art — that the Center asked him and O'Brien to help develop the Environmental Artist in Residence (EAIR) program to help artists incorporate environmental remediation into their work.

"They asked us to write a master plan, and we thought that was going to be it," says McCormick. But now he and O'Brien are back for 11 months to implement and manage the program.

Regardless of where he is working — Northern California, the Midwest, our own humid South — McCormick sees water issues that are universal. "We all have the same problem," he says. "The land has been paved too much. We're trying to spread the water in areas where it usually concentrates and allow it to sink into the ground and recharge the aquifers."

EAIR projects will be concentrated along Charlotte's greenways and the Carolina Thread Trail. The inaugural EAIRs are Kathy Bruce, a land-based environmental artist from New York; Bev Nagy, a Charlotte artist whose work has recently evolved from traditional basketry to mixed media works using recycled and found materials; and Tom Thoune, a Charlotte ceramic artist who has long experience with community projects. James Collins, Mecklenburg County's 2010 Urban Conservationist of the Year, is part of the team helping them adapt their work to meet this new challenge, and support is coming from numerous sources, including Foundation for the Carolinas; Blumenthal, John S. and James L. Knight, Duke Energy, Nathan Cummings, and Surdna Foundations; and the RBC Blue Water Project.

Throughout July, Thoune is working along Stewart Creek, in the Lakewood area off Rozzelle's Ferry Road. "Something interesting is happening at Stewart Creek," says McCormick. "The Carolina Thread Trail is just opening that community up."

This marginalized neighborhood at one time boasted a lake and amusement park; in the '30s, it was nicknamed the Coney Island of the South. A Duke Power substation now sits where the lake used to be. The only vestiges of the old Lakewood are some Civil Conservation Corps-style bridges over the creek.

Lakewood is no longer served by a comprehensive school, and it is impinged upon by train tracks, the freeway, and planes flying overhead. But there is growing neighborhood pride: The area now boasts 60 Habitat for Humanity houses, a community development corporation and an active neighborhood association. The community has welcomed the project, the creation of a "green gateway" to the neighborhood that, among other things, will mitigate contaminated stormwater runoff, provide interactive environmental education for neighborhood children, and beautify the neighborhood.

Unlike most other art in the public domain, these watershed projects are ephemeral, designed to break down as aquifers are recharged and native vegetation returns. And when a piece does break down, will another artist come in and do something in its place?

"No," says O'Brien. "It will be the forces of nature doing something in its place."

For more information regarding McCormick and his projects, visit www.danielmccormick.blogspot.com or www.mccollcenter.org.

Latest in Visual Arts

More by Barbara Schreiber

-

The numbers game at CPCC's Ross Gallery

Jul 6, 2012 -

Concurrent Rhythms in a small space

May 25, 2012 -

A nation of Rhythm-A-Ning

Apr 17, 2012 - More »

Calendar

-

WHISKEY TASTING: VIRGINIA HIGHLANDS WHISKY @ Elizabeth Parlour Room

-

NEW WINDOW GALLERY-Pat Rhea-ACRYLIC PAINTINGS-April 05-30 2024 VALDESE, NC 28690 @ New Window Gallery/Play It Again Records

- Through April 30, 12 p.m.

-

An Evening With Phil Rosenthal Of "Somebody Feed Phil" @ Knight Theater

-

Kountry Wayne: The King Of Hearts Tour @ Ovens Auditorium

-

Trap & Paint + Karaoke @ Zodiac Bar & Grill

-

Jessica Moss Makes the Gantt Center a Safe Zone for Local Artists 2

Flipping the script

-

Halo 4 earns critical hallelujahs

Plus, news on Mass Effect Trilogy, LEGO: The Lord of the Rings

-

Shaking it up in The Next Room, or The Vibrator Play 1