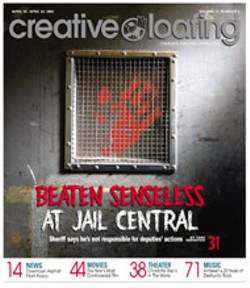

Mecklenburg Jailhouse Blues

Inmate lawsuits allege unprovoked, severe beatings at Jail Central

So far, Sheriff Pendergraph, who was elected by county voters in 1994 and presides over the county's jail system, has appeared to be fairly bulletproof in court, and none of these cases has yet made it to trial. Three of the seven cases against Pendergraph and the deputies allegedly involved in the beatings were filed by inmates acting as their own attorneys who lost quickly after attorneys for the sheriff danced circles around them. A fourth case was dismissed after a Charlotte attorney representing an inmate failed to file court documents in a timely manner. The same judge, US District Court Chief Judge Graham C. Mullen, has dismissed all of the beating cases that have failed to go forward.

But Pendergraph's luck may be running out. Former federal prosecutor Charles Brewer, now an Asheville civil rights attorney, appears to have launched a personal crusade to assure that former Mecklenburg County Jail inmates get their day in court. Brewer is now handling three prisoner-beating cases against Pendergraph's office, including an appeal of a case in which an attorney's error caused a dismissal. All three cases remain open, and he appears to have won an initial victory in one of them, after a judge refused the sheriff's request to dismiss it. Another Charlotte attorney is representing a client in a fourth case in which a judge has ordered a mediated settlement conference.

Brewer declined to publicly comment on these cases for this article.

In most of the beating cases against the sheriff and his deputies, the attorney for Pendergraph has argued that the sheriff shouldn't be held liable for the negligent supervision or training of his employees, or for their actions.

When CL asked Pendergraph in writing if he considered himself to be responsible for the actions of his officers while they were on duty, a spokesperson for the sheriff neglected to answer the question. After we submitted the question in writing to the sheriff a second time, he once again neglected to give us a straight answer.

Instead, spokesperson Julia Rush wrote, "The Sheriff has ultimate responsibility for hiring and firing (when appropriate) all employees of the Mecklenburg County Sheriff's office."

Like Pendergraph, Mecklenburg County, which was also represented by the attorney for the sheriff in these cases, similarly argues that the county bears no liability for the alleged misconduct of the sheriff or his deputies.

So, who's responsible for how inmates are treated at the jail? That will be up to the courts to decide. Because public officials, and in particular sheriffs, have strong legal protection from lawsuits at the state and federal level, winning a case against Pendergraph or his deputies will be difficult at best, regardless of whether the alleged beatings actually took place or not (see accompanying sidebar).

Legal skirmishes aside, the question remains whether the filing of so many similar cases indicates a brutality problem at the jail.

"I would say that that number of cases is pretty unusual," says Amy Fettig, a litigation fellow with the ACLU who represents inmates in abuse cases against prison officials. "It sounds like that's a jail that needs some investigation. The odds of a prisoner being literate enough to file a case and then to actually get it to that stage, [that means] the cases are probably representative of much more. Obviously if they keep getting dismissed and there is some brutality going on there, the sheriff is very confident that he doesn't have to make any changes."

Attorney Jean Snyder, trial counsel with the MacArthur Justice Center at the University of Chicago Law School, also handles inmate abuse cases. Snyder says that in jails with a systematic brutality problem, the cases that get filed are usually the tip of the iceberg because inmates rarely have access to the funds or legal assistance it would take to carry a case forward.

"An inmate has to get a lawyer to be interested in his case," said Snyder. "There isn't necessarily a lot of money to be made, which discourages the suits. They also require enough objective facts that the beating took place and was serious enough for somebody to find the claim credible. Many of these beatings go on in situations where an inmate's claim is not going to be considered credible even if the beating really did go on. They may be alone with the guard, and other guards likely will obey the code of silence and not provide any evidence that the guard did something wrong. Even if somehow there are credible reasons to believe the inmate, then they still have to get to a lawyer."

Despite the fact that Snyder has won suits on behalf of inmates in the past, she describes a sense of futility in trying to protect inmates in abuse-prone jails.

"There's very little sympathy for inmates even when they're in a jail where these aren't people convicted of crimes, these are people awaiting trial," she said. "In a sense, the inmates are sitting ducks for guard abuse because there can be a feeling that "we can beat these guys up, nobody's really going to care.' The issue is if it's a few bad apples who are doing this at a jail, is the sheriff's office really doing what it should to get rid of them?"

Sheriff's spokesperson Julia Rush told us unequivocally, "We don't beat or assault people. We do try to run a professional organization."

The following are the stories told by the inmates who've filed lawsuits against the sheriff, his deputies and, occasionally, against Mecklenburg County and other agencies. We must warn you that some of these beatings were so severe, it may be disturbing to read the accounts.

Dwight Cole was arrested for allegedly assaulting his girlfriend on August 19, 2001. Though the charges were later voluntarily dismissed by the District Attorney's office, he spent three days at Jail Central. According to his suit, his ordeal started in a holding cell in the basement of the jail sometime after 4:30am. The cell contained no toilet, and Cole claims he repeatedly asked security officers if he could use the bathroom because he needed to urinate. After his requests were ignored over the course of several hours by officers who he says laughed at him, Cole became desperate and urinated into the drainage hole in his cell. In response, Cole says, Deputy Sheriffs M.A. Carlson, John S. Malone, John W. Grimes and two other officers burst into his cell and threw him against the wall, after which he was beaten by Carlson and Malone while the other officers held him down. After the beating, he was strapped into a restraining chair and rolled into another holding cell. Cole hadn't had any liquids since 10:30pm the previous day and around 7:30am he began to ask for water. As hours passed and officers ignored his pleas for water -- at one point he says Carlson walked by with a Styrofoam cup marked H2O to taunt him -- he again became desperate. At one point, Cole banged his head against the door, begging for water. After a while, he figured that if he removed his belt and put it around his neck to look as if he was choking himself, someone would have to get him a drink of water. After that, he was taken to Mecklenburg County Mental Health where, he says, Deputy Sheriff Carl Mauldin, who was escorting him, pulled him back from a water fountain as he tried to approach it.

Once in the custody of Mental Health, Cole finally got a drink and explained to the doctor that he wasn't suicidal, but merely needed water. After he was returned to the jail, he was beaten twice more. In one of those incidents, he claims, he was held down by officers who were members of the Direct Action Response team (DART) while DART officer Gregory Griffith put on a black glove and beat him with a closed fist, busting his lips open.

While in jail, Cole claims he wasn't allowed to use a phone and that when he asked a representative from Mental Health who visited him in the afternoon of Aug. 20 why he had not yet been before a judge about bond, she explained that it was because he was on suicide watch. He begged her to help him, and he says she promised she'd see what she could do. Ten hours later, he was finally released.

In legal documents filed by Pendergraph and his detention officers, they deny the majority of Cole's story, including all the parts in which he claimed they did bodily harm to him. In their response, Pendergraph and the officers argue that they can't be sued by Cole because, among other reasons, as government officials, they have immunity against lawsuits like Cole's.

The Cole case is still ongoing. A judge ordered a mediated settlement in January, but the Pendergraph team is holding out for a jury trial.

Robert Foster, according to the lawsuit filed by his attorney, was awaiting trial on various charges including kidnapping and possession of a firearm by a felon in November 2001 when a fight broke out in another nearby cell. Because inmates in his cell were kicking the door and asking what was going on, Foster claims that detention officer Sean Spencer Stewman buzzed him from his plexiglass observation booth to ask which inmates were kicking the door. "You're sitting in the booth, you've got a better view than I do," Foster told him.

Detention officers came into the cell and took away Foster's mattress, a common form of punishment in the Mecklenburg County Jail. Foster, who felt he was unfairly being punished, requested that Stewman give him a grievance form. According to the lawsuit, Foster claims Stewman put on Nike gloves and replied, "I'll give you a grievance form." Foster says that an officer by the last name of Tolman handcuffed him and then stood by as Stewman violently beat and kicked him while he lay incapacitated on the floor. When it was over, Foster lay on the floor in a pool of his own blood, his mouth split open "from an area just below the side of his nose to underneath his chin on the opposite side." He bled from the eyes, mouth and ears due to the beating and severe blows to the back of his head.

An officer later wheeled Foster to the medical unit in a wheelchair where the inside of his mouth, the outside of his lips and his chin were sutured.

Because Stewman wrote him up for allegedly assaulting a prison staff member and other disciplinary problems after the alleged beating, Foster was given 100 days in the Administrative Detention Unit (ADU), where he says he was forbidden to make or receive phone calls or have visitors except his attorney, whom he wasn't permitted to call. Because of this, he was unable to seek outside medical help for his injuries by contacting his family or attorney except via mail.

According to the jail's policy on confining inmates to administrative detention, inmates can have visitation and telephone access unless those privileges are restricted as part of a disciplinary action.

As luck would have it, though, two days after the beating, Foster was due in Lincoln County for a pending traffic case, so Lincoln County deputies arrived at the jail to transport Foster to the Lincoln County Jail.

Because of his physical injuries from the beating, Lincoln County officials took Foster directly to the jail's medical ward. According to the suit, medical records there indicate that Foster had sutures both inside and outside his mouth and that two of his teeth were knocked out.

Foster's parents got involved after a nurse from the Lincoln County Jail called his mother, Carletta Foster, and told her Foster had been assaulted in the Mecklenburg County Jail. His father, Arnold Foster, pleaded with a Lincoln County judge to hold Foster in Lincoln County, but the judge couldn't oblige him because of pending cases in Mecklenburg. Foster's case in Lincoln County was continued because, given the condition of his mouth, he couldn't speak well.

Foster's parents didn't give up. Requests made by both parents to high-ranking officials within the Mecklenburg sheriff's office for information about their son's condition, and for an investigation, resulted in promises of returned phone calls that never came. A letter from Carletta Foster to Sheriff Pendergraph, requesting that he investigate the beating, was answered by Commander Bruce Treadaway. Appropriate action had been taken, Treadaway wrote in his November 27 reply, but due to the North Carolina Privacy Act, we are limited in what we can disclose." The privacy act bars public perusal of government employee personnel records.

Because it was recently filed, Pendergraph has not yet responded to Foster's suit.

Paul Midgett's lawyer didn't elaborate on the fine details of the severe beating Midgett received while incarcerated in the Mecklenburg County Jail in May 2000, but Midgett's criminal file at the courthouse contains several letters from his father, George Midgett that give some idea. After seeing the severity of Paul Midgett's injuries from the beating, George Midgett joined the ranks of other desperate parents who've lobbied the courts and public officials to keep their sons from being transferred back to the Mecklenburg County Jail. George Midgett feared that detention officers at the jail might do his son -- who was a federal prisoner awaiting trial on robbery-related charges -- further harm if he were held there before scheduled court appearances. In a series of memos faxed to his son's attorneys between August and October 2000, George Midgett wrote, "under no circumstances should Paul be held over at the Meck. County Jail because they would probably kill him." In another memo written after it appeared that Midgett would be moved to Charlotte temporarily for a legal proceeding, George Midgett wrote, "This reference to being moved to Charlotte frightens Paul and scares Loretta and me. There is just no way that Paul can be kept, even for a few hours, in either of the two Mecklenburg County Jails. . ."

In their response to the charges made by Midgett in his lawsuit, the attorney representing Pendergraph, Mecklenburg County and the officers Midgett claimed had assaulted him didn't deny that Midgett had been beaten, but argued that "prison officials can't be held liable under for negligent supervision or training of their subordinates" and that the county should be dismissed from the suit "regardless of Plaintiff's allegations since it bears no liability for the alleged misconduct of the sheriff or its deputies."

As they had in several other prisoner-initiated cases against them, Pendergraph's lawyer argued that the sheriff is a state officer rather than a county official and couldn't be sued for constitutional violations because the state and state officials have immunity from such suits.

US District Court Judge Richard Voorhees didn't buy Pendergraph's arguments, and denied both Pendergraph and the county's motion to dismiss the case. The case remains open.

Roger Byrd was a federal prisoner who was transferred to the Mecklenburg County Jail in May 1997 to await re-sentencing. Even though he immediately told prison officials that he had diabetes, which required a special diet and treatment, Byrd says they insisted he didn't have the disease. As Byrd became increasingly ill, he says his pleas for medication to control his glucose level were repeatedly ignored. By the time he called his mother on September 17 to ask her to lobby his jailers for help, he was extremely ill with the symptoms of acute diabetes. Despite her calls to the prison, he received no treatment and, six days later, was taken to Carolinas Medical Center in a near-comatose state and with what he believed to be a temporary loss of vision. Byrd eventually learned that he suffered a permanent loss of vision typical of untreated diabetes that will eventually cause him to become blind, according to the suit. In their response to Byrd's suit, the sheriff's department didn't deny the allegations Byrd made, but said the suit should be dismissed because Byrd waited until 2002 to file the suit and the three-year statute of limitations on suing them had passed.

"(Byrd) knew, even before he was hospitalized on September 23, that he was getting sicker by the day because of the jail's refusal to provide him adequate medical care for his diabetes," the lawyer for the sheriff wrote. "The fact that the loss of vision was not diagnosed as permanent until March of 2000 is of no consequence."

Pendergraph's legal response bears little resemblance to the chronic illness policy directive released by the Mecklenburg County Sheriff's Office in March 1998. According to that policy, those with chronic illnesses, which includes prisoners with diabetes, are supposed to be assessed upon their arrival at the jail. Within 10 days, the inmate is supposed to meet with a physician who has evaluated his tests or lab work to assess his status. After that, their status is supposed to be reviewed "on a continuous basis," or a minimum of every 90 days.

In Byrd's case, US District Court Chief Judge Graham Mullen accepted Pendergraph's argument that the statute of limitations had passed, and dismissed him from the suit.

Willie McKinnon spent two days in the Mecklenburg County Jail in September 2000 after he was charged with misdemeanor assault on a female and communicating threats, charges on which he had not yet been convicted. In his suit, which was written by his attorney, McKinnon describes the same abusive jail policies other inmates have described in at least 10 suits against Pendergraph and his deputies since the mid-1990s. Because, they claim, the jail is kept at a very cold temperature, several inmates have sued the sheriff over the years for what they describe as the jail's policy of "torturing" inmates by forbidding them to use the blanket the prison provides them between the hours of 4am and 9pm.

In the suit McKinnon filed against Pendergraph and nine other sheriff's office employees, McKinnon admits he wrapped himself up in his blanket to keep warm and that he protested when a detention officer, referred to as "John Doe #1," threatened to take his sleeping mat, or mattress, and his blanket, the standard punishment for breaking that rule. When John Doe #1 and a sergeant demanded he turn over the items to them, he refused but said he wouldn't resist their efforts to seize the items.

According to the suit, the two maced and handcuffed him, and after the nurse at the jail refused to treat him, he was taken back to his pod. Soon afterward, five members of the DART team showed up and told him to lie on the floor, place his hands on his head and cross his legs, which he did. He was then beaten and kicked. McKinnon says that after the beating, they dragged him out of his cell, along the floor and over steps and other obstacles to a cell in the Administrative Detention Unit, where they left him in handcuffs. They returned a few minutes later and dragged him to another cell.

McKinnon received medical attention after his beating, including sutures to a gaping laceration to his foot that prevented him from walking. On the way back from the infirmary, the two detention officers who transported him back to his cell deliberately ran his chair into walls, corners and elevator doors.

It's difficult to know who's telling the truth about the rules enforced in the jail. The jail climate control policy that went into effect last April says that the temperature in the jail isn't supposed to get above 85 degrees in the summer or below 68 degrees in the winter. According to temperature data sent to Creative Loafing by sheriff's office spokesperson Julia Rush for two days in February and three days in January of this year, temperatures at the jail ranged from 70 degrees to 74 degrees. Rush says that it's up to the discretion of the pod officer whether inmates can use their blankets between 4am and 9pm. Since September, detention officers have been banned from taking mattresses away from inmates as a form of punishment or without authorization.

If this is the case, one can't help but wonder why so many inmates would go to the trouble of suing the sheriff over the allegedly cold conditions in the jail. If their aim was to strike back at their jailers, why not make up something more substantive? Perhaps those questions will be answered in this case, which is being appealed.

Former inmate Christopher Oxendine, acting as his own attorney, filed a suit against Pendergraph, Sergeant James Elkins and the Mecklenburg County Government. Oxendine says that while he was confined to the jail in November 1999 on stolen vehicle and possession of cocaine charges, Elkins and other officers led him from his housing area into the hall, where he argued with Elkins. Oxendine claims that while he was handcuffed, Elkins grabbed him violently by the pants and collar and threw him into a cell. He claims Elkins removed the handcuffs and said, "I'm going to give you a chance," then hit Oxendine in the mouth and eye with his fists. Oxendine claims he didn't fight or resist while Oxendine beat him. The beating resulted in seven stitches to the left side of Oxendine's mouth, he said. In an answer to Oxendine's suit, Elkins claimed that Oxendine became "increasingly belligerent and verbally abusive while in the hallway and that he repeatedly told Elkins that he knew what time he got off duty and would kill him or have him killed." Elkins claims that Oxendine lunged at him with no provocation and that he defended himself by punching him twice in the face before he could be re-handcuffed.US District Court Chief Judge Graham Mullen dismissed Pendergraph from the suit because Oxendine failed to "allege any personal conduct by Sheriff Pendergraph or that Sergeant Elkins was acting pursuant to a policy or custom of Sheriff Pendergraph." Mullen threw the case against Elkins out after legal papers sent to Oxendine were returned as undeliverable.

David Giovanni Richardson claims a detention officer at the jail by the last name of Darlington slammed him on the floor and rammed his head into a wall after a verbal confrontation between the two on September 29, 2000. "This incident happened because Detention Officer Darlington and I had had words about his trying to disrespect me and other inmates," Richardson wrote in his lawsuit.Less than two weeks later, Richardson claims that Darlington came to his cell when he was asleep.

"I was afraid he was going to assault me again," Richardson wrote. "I jumped back when he flinched at me as if to hit me. I swung at him from reflex. We scuffled for about 20 seconds. His assigned partner Detention Officer Moore came in to assist him and they had me laying on my stomach, not resisting."

Richardson, who was incarcerated at the jail on robbery charges, says other detention officers, including Sergeant James Elkins and a detention officer by the last name of Smith entered the cell and kicked him in the head and the face. When they were through beating him, Smith took him to "medical" for treatment of his two busted lips, swollen nose and chipped tooth.

Because he couldn't afford a lawyer, Richardson represented himself and quickly lost the case. US District Court Chief Judge Graham Mullen dismissed Richardson's case against Darlington and the other officers because Richardson "had not exhausted his administrative remedies," for complaining to jail officials about the alleged beating before filing the case in court.

Immune DeficiencyOld legal quirk may give sheriffs free reinAs inmatesacross the country have learned, successfully suing a public official, and in particular a sheriff, for beatings or other abuse they've suffered in the country's jails is about as easy as running a marathon on one leg. There are often so many legal hurdles to cross before a jury can even hear your case, it almost seems as if it's not worth the effort to sue, no matter how many gory pictures you have of what detention officers did to you.

If the average guy on the street beat someone else senseless for no particular reason and the victim could prove it, the odds are that a jury would award the victim a large sum of money. But when the folks allegedly doing the beating are sheriff's deputies, and when the person to whom they answer is the sheriff, then legally speaking, the rules of the game are completely different.

It all goes back to a concept in English common law called sovereign immunity that essentially says that government officials can't be sued for their actions, no matter how much damage they cause. Because most states, including North Carolina, have statutes that say that the common law is enforced unless changed or abrogated, and because the NC legislature has never passed a law abolishing sovereign immunity, it still applies here.

Further complicating matters are the various shades of sovereign immunity. In one prisoner beating case filed against Pendergraph and his employees, their attorney argued that they are entitled to qualified immunity on the federal claims against them, public official immunity on the state law claims against them, and barred from recovering any damages under state law by sovereign immunity.

Since sovereign and other official types of immunities are afforded to state officials, sheriffs around the country started arguing that they were state officials and thus entitled to immunity from lawsuits related to their professional performances. The issue is still undecided in North Carolina, where some judges have ruled that sheriffs are state officials and others have ruled that they're not.

The US District Court for the District of North Carolina has said that in suits under federal civil law, the county sheriff is a local official who doesn't possess Eleventh Amendment immunity from a suit in federal court. Attorneys for Pendergraph have argued that that decision was invalidated by a subsequent decision by an NC appellate court that a North Carolina sheriff and his deputies function as state officials.

In suits filed by former inmates of Mecklenburg County Jail Central, one judge, Graham Mullen, bought Sheriff Jim Pendergraph's argument that he's a state official and thus is immune from being sued. In another case in which the same legal arguments were made, Judge Richard Voorhees ruled that Pendergraph isn't a state official. To further complicate matters, some judges are accepting the idea that the ruling in an Alabama case called McMillian v. Monroe County, in which the US Supreme Court decided that a local sheriff was a state employee, applies to similar legal questions in North Carolina. Others aren't.

"They are trying to broaden what the Supreme Court has actually said in McMillian and make it a badge of immunity for sheriffs everywhere rather than a very fact-specific, Alabama-specific ruling," said Amy Fettig, a litigation fellow with the ACLU who represents inmates in abuse cases against prison officials.

The question of whether that defense will work in North Carolina will probably have to be settled by higher courts, she said.

Of course, there are ways around immunity, said Jean Snyder, trial counsel with the MacArthur Justice Center at the University of Chicago Law School.

"One is if the inmate alleges a widespread practice or a policy of the sheriff's office," Snyder said. "But the problem with suits against the sheriff is that the sheriff wasn't personally involved in the events."

That essentially forces inmates' attorneys to prove that officials intentionally violated their civil rights, and that they knew they were violating their civil rights while doing it, a legal feat that's very difficult to accomplish.-- Tara Servatius

Latest in Cover

Calendar

-

Queen Charlotte Fair @ Route 29 Pavilion

-

NEW WINDOW GALLERY-Pat Rhea-ACRYLIC PAINTINGS-April 05-30 2024 VALDESE, NC 28690 @ New Window Gallery/Play It Again Records

- Through April 30, 12 p.m.

-

TheDiscountCodes

-

Wine & Paint @ Blackfinn Ameripub- Ballantyne

-

Face to Face Foundation Gala @ The Revelry North End