When I drove my friend Lisa Max Stybor, an artist and design professor from Germany, down to Winthrop University in Rock Hill, SC, last week, I didn't know what to expect from the invitation that took us there.

The invitation for Professor Stybor, a Fulbright alumna, was to speak about painting and teaching design at the resurrected Bauhaus in Dessau (outside Berlin) to students and faculty at Winthrop's School of Visual and Performing Arts. Stybor had been invited by Michael Simpson, a fine painter himself and an adjunct instructor of art at both Winthrop and UNC-Charlotte.

Having met Stybor a few days earlier, Simpson no doubt recognized a fellow artist who loved the natural landscape and was very serious about painting. Stybor had already met several groups of working artists in Charlotte the week before, and she responded favorably to the invitation.

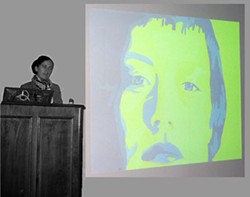

A small band of faculty and students gathered in the converted Carnegie Library building that now houses art department studios, classrooms, a lecture hall and exhibition spaces to listen and look at images as Professor Stybor spoke about her extensive experience teaching at the Dessau Bauhaus -- that famous bastion of Modernism -- now disguised under its new, pedestrian title of Hochschule Anhalt (Anhalt University). Stybor also spoke at length about her own work as a practicing "plein-air" painter, someone who does a lot of her work in-situ, in the open air.

Like me, Stybor must have been disappointed at the small number of people in the audience. But what first appeared to be meager turned out to be attentive.

The German visitor teaches design to architects and engineers, and she began by showing life-sized student drawings in PowerPoint -- so that students could "learn about themselves." She also talked about a tornado and a big fire that influenced her work, and about the five years (1995-2000) when she painted in red only, with oil sticks on paper that measured around 5-1/2 x 6 feet. These paintings on paper, mounted later on canvas, had an intensity that a full color palette would have lost.

Stybor explained to her audience that she guides her students to experience the outdoors, where "the feeling in space corresponds to the feeling in the body." She literally moves the classroom to the landscape "to get a feeling for nature."

As the talk came to a close, a few stayed to ask a question or two of the woman with the foreign accent. It was impossible to tell whether the students, resplendently lazy on that soft, early spring day, really related to the idea of making drawings on site in the extreme landscapes of Iceland, Sicily, Corsica and central Oklahoma. Following Stybor's deeply interesting talk about her teaching and art making, I overheard one student comment to another in the hallway outside the lecture hall, "I did like the red paintings." Maybe this throwaway remark was a compliment; I couldn't tell. Studio art students are often focused entirely on their own work -- it just wasn't the sort of response I was expecting.

There was a tinge of the surreal in our visit to the small South Carolina campus. Maybe the juxtaposition of the docile university ambiance (decidedly American in design and concept), Stybor's discussion of big ideas, the images from Germany and elsewhere, and the pleasant Vietnamese restaurant where we had lunch afterward caused this feeling.

With the ideas and images from old Europe still floating in our minds, we opened the fine old doors, still heavy and correctly weighted, and entered the lobby of a former post office where Michael Simpson has his personal studio. I was visited at once by a whiff of déja vù. It was the kind of old interior from the past that has a "hush," one that seemed to echo from the real materials: real stone -- cool to the touch -- real plaster, real bronze or brass.

Around us were the sturdy remnants of public rooms once rich in ornament. It would be difficult to imagine a less-Bauhaus design than the one we were stepping into, one well worth preserving. This contrast seemed to sum up part of the Bauhaus' appeal and demise, all in one. For a few brief years in pre-Nazi Germany, avant-garde artists and architects sketched, modeled and made visions of the future that were tantalizingly real but out of reach.

With the same kind of intensity that came through in Stybor's talk, artists in the '20s and '30s crafted the way they wanted to change society; the vision was too radical for Hitler, who closed the school with a gesture that eventually repressed all modern art and architecture. But the Bauhaus legacy lives on in almost every American art and architecture school in the work of freshmen students as they explore the language of form, color and space, learning about themselves and refining their sense of space. In their working lives, these future artists and architects will each find their own place in the dialogue between the vision of form and space the Bauhaus legacy offers -- and the cozy conventionality of most of our contemporary surroundings.

Stybor explained her mission succinctly. "I am not interested in reality itself," she said. "I want to open the students to the next step of design; to look around, open their senses. It's important to take a walk in nature to gain understanding and inspiration about the body and the building."

I like to think that the comment I overheard when that guileless student said, "I did like the red paintings," represents more than I originally believed. Maybe he'll remember something about those five years of extensive and intense study into the color red.

For more information on the Bauhaus, go online to www.un-urbanism.de/live/site/wc/index.php and www.bauhaus-dessau.de/en/index.asp.

Lisa Max Stybor, professor of form and design from Anhalt University, Dessau, speaks at Winthrop University

Latest in Visual Arts

More by Linda Luise Brown

-

Turbulent Waters

May 3, 2006 -

SOUP for the Soul

Apr 19, 2006 -

Spring Forward

Apr 5, 2006 - More »

Calendar

-

An Evening With Phil Rosenthal Of "Somebody Feed Phil" @ Knight Theater

-

Kountry Wayne: The King Of Hearts Tour @ Ovens Auditorium

-

NEW WINDOW GALLERY-Pat Rhea-ACRYLIC PAINTINGS-April 05-30 2024 VALDESE, NC 28690 @ New Window Gallery/Play It Again Records

- Through April 30, 12 p.m.

-

Trap & Paint + Karaoke @ Zodiac Bar & Grill

-

LIVE MUSIC FRIDAYS!!! @ Elizabeth Parlour Room

-

Fall Guide: Upcoming festivals, comedy shows, visual arts events and more

-

Failure To Communicate

Worthy play could use more nuance

-

Susan Brenner Examines Upheaval While Celebrating Trees

Chaos and beauty