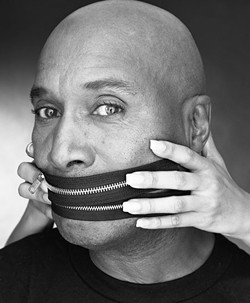

"Humor is powerful. People shouldn't lose it."

Maybe so, but make no mistake: There will be tears Sept. 7, in the McGlohon Theater at the Paul Mooney show. Bright, cleansing tears of hyperventilating laughter. Angry, shocked tears of offense. Maybe the stinging tears of public castigation. It's all part of his duty as one of the nation's last titans of socially critical comedy.

Don't come expecting "black people be like" jokes; you'll get your feelings hurt. Watching Mooney, 73, talk about race is a revelation: scalpel-sharp, freight-train blunt, cold as the icy deep. The fact that he's joined on this tour by Dick Gregory, another legendary comedian who is decades deep in activism, means that Charlotte is up for a special show indeed.

Even if you somehow missed Mooney's sketches "Negrodamus," "Ask a Black Dude" and "Mooney on the Movies" on Chappelle's Show, chances are you caught his humor growing up, on In Living Color or reruns of Sanford and Son and Good Times. His comedy specials The Godfather Of Comedy (2012), It's the End of the World (2010), Know Your History: Jesus Is Black; So Was Cleopatra (2006) and Analyzing White America (2004) solidified his cult following, but Mooney's most popular work came about during his decades-long writing partnership with Richard Pryor. In addition to serving as the head writer for The Richard Pryor Show, where he launched the careers of luminaries like Robin Williams, he helped pen Pryor's classic routines on Bicentennial Nigger and Live on the Sunset Strip albums.

Mooney's brother Rudy Ealy describes him as being "tall as a tree, black as coal and talks more shit than the radio." That may be, but it's clear when Mooney is dissecting the American psyche, every word he speaks is backed with full conviction. Other comedians tell jokes, but Paul Mooney tells the truth — his side of it, at least.

He was born in Shreveport, Louisiana, and his family relocated to California when he was 7, where he was mainly raised by his grandmother. Early on, he discovered a talent for making people laugh, so he did what most young people only threatened to in those days; ran off and joined the circus. That stint as a ringmaster groomed him for a career in showbiz, though he'd already begun writing comedy routines and doing stand-up to pay the bills. While scraping by in a rundown apartment on Sunset Boulevard, he met a young Pryor and that magical thing, chemistry, happened. Together, their writing blossomed into something no one could have predicted. Mooney wrote of that time in his memoir, Black is the New White:

We are the only black guys who can make the scene in Hollywood. We are groundbreakers, accepted at all the clubs, invited to all the parties. When we break into it, Hollywood is still a closed, racist town. The place has never seen anybody like us. We are fearless. We go everywhere. We break down barriers. We still get harassed by bigots and cheated by the system, but it never stops us.

In 1969, Mooney got on TV with Playboy After Dark. Hired as one of the "pretty people" to dance with Playmates and add to the ambiance while host Hugh Hefner talked to celebrities, he forged connections with people in the industry, but with the exception of Pryor had trouble making inroads as a television writer. The more he saw the entrenched racism of Hollywood, the hotter his wit burned. He pushed back, both verbally and in his comedy — and got a surprising response.

"They were in love with me; they couldn't get enough of me," Mooney shares from the road. "White people always have their favorite pet black people, and I had those looks. I could say anything. Black don't crack. I'm glad the Indians invented canoes, because the white folks would've swam to Africa to get to us."

Mooney's riffs are spring-loaded with side eye for American hypocrisy around race, and wholly cathartic when heard. False media representation; the devaluation yet commodification of black style, dance and culture; and especially the half-history taught in schools all come under fire. When he hits on historical subjects, the laughs crackle with pain. Mooney believes Americans in general, and especially whites, don't like looking at our history, because "it's too ugly."

"They used to have us living in their houses and attics," Mooney says about slavery in Know Your History, "but now that we're free they don't want us in the neighborhood. If slavery were reinstated tomorrow, they'd be on their porches with open arms. 'Welcome home!'"

Virgins to a Mooney show should practice fixing their faces and come armed with thick skins; Mooney sometimes picks one to ride.

"They're not really virgins, are they? Everybody is somebody's ho," he says. "They know, white people aren't stupid. We learned [prejudice] from the best. They've got black people who pass for white in their families. They talk to them. They know, they pretend they don't, but they know."

When it comes to black dysfunction, Mooney is a bit more forgiving, but only just.

"A lot of them were frightened, honey. If somebody will lynch you, burn you and hang you from a tree, you wouldn't want to talk about it either. Selective memory goes for all them, black and white."

On Analyzing White America, a white woman in the audience took offense to his act, and he opened up both barrels: "See, I'm just like you. I will sell your babies and go home and sleep like one," he said on the recording.

Harsh words, but when Americans cling to the idea of post-racialism in the face of police brutality and blatant oppression of black citizens, an unvarnished look at our past and present is vital.

Mooney won't disclose the exact topics of the Charlotte show but says current events practically write the routines for him. "I like things that are funny that you can't get away from, that are inescapable. Things that are funny even if you don't think it's funny, or you think you shouldn't laugh," he says.

After more than 40 years of pushing the envelope, Mooney says there is no joke he's ever done that he would take back. Asked if he ever wondered how much this brand of comedy has cost him, or if he thought he might've been bigger if he'd toned himself down, Mooney scoffs.

"Nothing costed me nothing. They have to pay for it. Even if you're an atheist and you don't believe in God, you have to acknowledge it is what it is. There's no escaping it. Everyone pretends, but everyone knows. It's always white power making the rules. Always fighting people; they use fear. It's about property. If they never owned us, we'd be friends."

Speaking of...

Latest in Feature

More by Emiene Wright

Calendar

-

An Evening With Phil Rosenthal Of "Somebody Feed Phil" @ Knight Theater

-

Kountry Wayne: The King Of Hearts Tour @ Ovens Auditorium

-

NEW WINDOW GALLERY-Pat Rhea-ACRYLIC PAINTINGS-April 05-30 2024 VALDESE, NC 28690 @ New Window Gallery/Play It Again Records

- Through April 30, 12 p.m.

-

The Comic Strip (Comedy + Sip & Paint) @ Superstarz

-

Uptown Area: R&B Sip & Paint @ Superstarz

-

Holiday Gift Guide

26 ways to shop local this holiday season

-

Charlotte Film Festival Features Distinct and Different Voices

Diversity and discovery hit the big screen

-

Fall Guide: Upcoming festivals, comedy shows, visual arts events and more