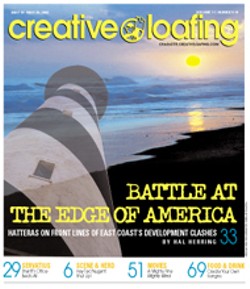

Battle at America's far edge

Hatteras on front lines of East Coast's development clashes

By Hal HerringBut before development is allowed to snuff out the town's identity -- taking with it one of the last remnants of the old America of rugged individualists making a living from their own talents, well out of reach of the corporate world -- there will be a struggle.

The fate of Hatteras Village now seems to hinge on one proposed high-density development of 5.77 acres, situated on a spartina grass estuary known as The Slash, at the north edge of town. Prominent and controversial developer Skip Dixon of Nag's Head, and his partner, NC State Senator David Hoyle of Gastonia, plan to build a 45-unit condominium complex on the site. The Dixon/Hoyle Project, also known as Slash Condominiums, features a 46-slip marina, swimming pool, and its own private "package facility" for treating waste. Residents of Hatteras Village say that the Slash project, coming in the wake of a flood of other very high profile developments by Dixon and other developers, is the straw that broke the camel's back. They're prepared to fight a final battle for their town, and they've met two worthy adversaries in Sen. Hoyle and Mr. Dixon, successful men of business who have clear battle plans of their own.

"We were just living our lives, never realizing that something like this could happen to us," said Ricki Shepherd, who has run the Hatteras Harbor Seafood and Deli for the past two decades, and is current president of the Hatteras Civic Association ("Not a job coveted by anyone," Shepherd notes). "The development here has just been insane. As a community, the Slash Condos project has shown us the line that we have to draw if we're going to survive. This is the final line."

The 10-member Hatteras Civic Association has unanimously condemned the Slash project, perhaps the only time in living memory the Association has been unanimous about anything, Shepherd said.

The Outer Banks has always been a place where the word "unanimous" had no meaning whatsoever, and residents tend to like it that way. It's a measure of the attraction of this harsh and exposed place that the same family names found in the 1850 census -- Midgett, Burrus, Willis, Oden, Ballance, Austin -- crowd the narrow telephone book of 2003. They have been joined, especially in the past 40 years, by others who seek the increasingly rare combination of isolation and the sea -- surfers, working artists, fishermen of various stripes, watermen displaced from coasts destroyed by development, and people who just want to be left alone.

The Outer Banks is still one of the far edges of the world and, like frontiers everywhere, it's inhabited by men and women who value hard work and individual freedom, who are suspicious of government, adamant about private property rights, and reluctant to meddle in other people's business plans. The membership of the Hatteras Civic Association includes descendants of the original settlers -- Bill Ballance, Durwood and Virgil Willis, Jane Oden -- who hold strongly to those values, and who probably would never describe themselves as environmentalists. For a long time the go-your-own way individualism of the Outer Banks, the lack of any unified vision, was a strength, part of the rich culture of the place. Now, a convergence of events has made it an Achilles' heel.

Coastal conservationists say they watched the slowing US economy with optimism at first, hoping it would put the brakes on out of control development in ecologically fragile and very finite places like the Outer Banks. But quite the opposite has occurred. Wary investors have found coastal real estate and low interest rates to be the best antidote to their anxiety. Population growth in Dare County, which includes the Banks, is double the average for North Carolina, which is itself experiencing growth double the national average. The average cost of the homes being built in Dare County -- 1,144 of them in 2002 -- is 50 percent higher than the average for the state. Jan Deblieu, the Cape Hatteras Keeper for the Coastal Federation, and a longtime Outer Banks resident, explains, "When that market started to fall after September 11, we started to see a wave of new development. Now it has built to the point where we're under siege here. There doesn't seem to be any restraint at all." Heaven At A High Price

Life on the Banks, as chronicled by talented historians like David Stick, or by storytellers like Ben MacNeill, who wrote The Hatterasman, or by Ms. Deblieu, who wrote Hatteras Journal in 1987, has always been hardscrabble, a battle for existence in a place where the most violent and the most giving elements of the planet converge.

Latest in Cover

Calendar

-

Wine & Paint @ Blackfinn Ameripub- Ballantyne

-

Face to Face Foundation Gala @ The Revelry North End

-

An Evening With Phil Rosenthal Of "Somebody Feed Phil" @ Knight Theater

-

Kountry Wayne: The King Of Hearts Tour @ Ovens Auditorium

-

Queen Charlotte Fair @ Route 29 Pavilion

-

Navigating the thrilling intersection of sports and betting in North Carolina

-

Canuck in the Queen City 7

A Canadian transplant looks back at her first year as a Charlotte resident

-

Homer's night on the town 41

If you drank a shot with the Knights mascot on Sept. 20, you were basically harboring a fugitive