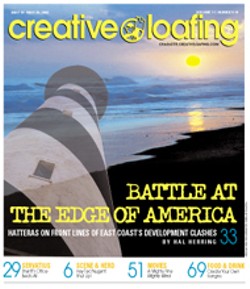

Battle at America's far edge

Hatteras on front lines of East Coast's development clashes

By Hal HerringPage 4 of 7

Hoyle's partner, Skip Dixon, has a local reputation for being an aggressive and successful developer. He's a very plainspoken man who tends to let the chips fall where they may.

"We have a small, vocal group of very nasty people in Hatteras, and we've had a bellyful," Dixon said. "We feel that what we are doing is within our rights, and we aren't going to sell the property, or donate the property to anybody. We've tried to please these people, and there's no way to do that, so fuck "em. I'll eat that property grain by grain before I'm forced by a bunch of obstructionists to do anything that I don't want to do."

Dixon said that, contrary to what some Hatteras residents seem to believe, Sen. Hoyle's political position has actually been a hindrance to the project. "Because of his position, we cannot just go to the agencies ourselves and check on the progress of the permits," Dixon explains. "We have to go through engineers and lawyers, and it takes so much more time. It is extremely frustrating."

Like Sen. Hoyle, Dixon reminds the people opposing his project that the lack of zoning gives him a lot of options. "I can build whatever I want. I can put a crematorium in there, whatever. I can cut that land into 10 lots, build a 10-bedroom house on each one, and put it all on a septic tank, let the wastewater pour right down into the ground. Instead, we've got a multi-family development, with its own wastewater treatment plant. Believe me, if you really care about the environment, you'd support our project, not oppose it."

But the planned wastewater treatment plant worries residents, too. Some of the oldest houses in Hatteras Village have holes drilled in the floors (usually covered by rugs) to drain away floodwaters. According to Ricki Shepherd, the site of the Slash project has been completely flooded by storms six times in the last 12 years. The developers are adding several feet of fill to the area, which will displace some of the floodwaters ("To where?" Shepherd asks, and answers her own question. "Into the rest of the village, that's where.") in future storms. But in the aftermath of Hurricane Emily in 1993, state floodplain maps were revised to place all of Hatteras Village within the 100-year floodplain. A combination of storm surge and rainfall during Emily caused floodwaters that were described as "waist deep" in the village.

"Waist high waves broke through windows and rolled through living rooms," wrote Jay Barnes in his book, North Carolina's Hurricane History. Surveys taken after Emily's storm surge showed floodwaters as high as 6.98 feet.

Joe Lassiter, an environmental engineer hired by Dixon to oversee and develop the treatment plant, says that the planned treatment facility will be built one foot above what is called "the base flood elevation," of 6 feet, as required by law.

Such "package facilities" for wastewater treatment have a mixed reputation. At best, they represent what Rick Scheiber of the North Carolina Division of Water Quality calls "a compliance challenge." That challenge becomes greater, Scheiber says, once the plants become the property of the homeowners. "You need the expertise, and everybody has to contribute the money, to keep these plants operating to standard," he said. "Sometimes the homeowners are able to do that, sometimes they aren't." He adds, "A lot depends on how sensitive your site is, how much land you've got for dispersal, how close to the water it is."

"Did the community a favor"

Initially, the development plans called for dredging a 1500-foot channel through the Slash estuary to permit passage of boats into what the developers call "the marina body."

The public reaction to this proposal was angry and immediate, and was reinforced by written comments from state and federal agencies that cast doubt on the proposal's chances. The developers eliminated that problem by simply dropping the dredging proposal from the project. But both Hoyle and Dixon said they would still build the marina, even though the estuary is only one to three feet deep, and most boats will not be able to enter or leave it.

With the dredging question out of the way, the North Carolina Division of Coastal Management issued a FONSI (finding of no significant impact), allowing the clearing and filling of the property to begin.

According to Doug Huggett of the State Division of Coastal Management, it is not particularly unusual for developers to drop controversial permit requests in order to keep a project moving. "There is nothing to stop them from revisiting this permit later," Huggett said, "and it is very likely that they will."

Latest in Cover

Calendar

-

Queen Charlotte Fair @ Route 29 Pavilion

-

NEW WINDOW GALLERY-Pat Rhea-ACRYLIC PAINTINGS-April 05-30 2024 VALDESE, NC 28690 @ New Window Gallery/Play It Again Records

- Through April 30, 12 p.m.

-

TheDiscountCodes

-

"Blood Residue Analysis of Paleoamerican Stone Tools in the Carolinas" @ Native American Studies Center

- Fri., April 26, 12-1 p.m.

-

Brightfire Music and Arts Festival @ GreenLife Family Farms

-

5 Online Player Communities to Join in Michigan

-

A beginners guide to online sports betting in the US

-

I Changed my Sex. Now What?

Scott Turner Schofield's rapid transit to a new identity