With all due deference to Christopher Columbus' faulty sense of direction and penchant for hasty declarations, the term "Indian" is inaccurate — "Native American" is the better description. "Native American" accounts for who these people are — the ones who were here first and the first Americans. But in deference to Hopalong Cassidy and Roy Rogers, and with a generalized revulsion for the continuing mania for the politically correct, the term Indian will be used in this text.

I recognize my forebears, for good and ill, took possession of this land formerly owned by no one. We knew how to own land. The antiquated and cosmically correct American Indian concept of "ownership of land" roughly parallels current ideas on who "owns" the chilly atmosphere of Neptune — no one owns it, it can't be owned.

But American land can most certainly be owned. European settlers came to occupy the land and, in time, that required liberation of the land from those folks wandering around in the woods. The occupation wasn't planned, only necessary. The occupation was a little disruptive. The natives learned the rules of the occupation and soon realized the rules exempted them from the stage. They were not players, but obstacles to be removed or props to be ignored.

The Native American population did not appreciate that role. With courage, violence, grit, resolve and wit, they have staked a more significant role in our national drama. After 300 years of survival, Native Americans have, in some quarters, begun to blossom and thrive. They are a force still occupied, but no longer relegated to a distant storage room. American Indians are players on the new American Stage, and they are increasingly writing their own scripts. This exhibit showcases where our Native American neighbors are now, who they are, what they look like, and what they, and we, have managed to salvage from our extended visit.

They're everywhere. Look around.

The old woman in the frilly country dress is ageless. She holds her unfinished double weave basket in one hand and rests a fist on her hip. The two deepest wrinkles on her face are her eyes. Her eyes are slitted and slope down on the outer edge, a shape borrowed from her forebears and accentuated from countless days under the sun. A smile is tucked into her closed mouth. Esbee Gibson speaks Choctaw and very little English. She believes the growing demand for Choctaw baskets means that at least part of her culture will survive. Her gaze and her posture say, "I've always been here." Many younger members of different tribes across America wrestle with reasonable identity conflicts. Esbee Gibson does not.

There are few counties in South and North Carolina with no Native Americans. Closest to home in Charlotte are the Catawba Indians, a tribe recently close to dissolution and now thriving with newly recovered land and newfound recognition. More than 40,000 Lumbee Indians live in Robeson County alone, the most populous Native American tribe on the east coast. Counties surrounding Robeson — Scotland, Hoke, Cumberland, Sampson, Bladen and Columbus — are home to thousands more. The Cherokee tribe is concentrated in the far southwest corner of NC, in Swain, Jackson and Graham counties, on the Tennessee border.

Billy Smith's hair is grey and wiry and pulled straight back over his skull and tumbles down over the collar of his great coat. He wears a string tie bound with an onyx and silver clasp. He gives the camera a closed mouth half smile under half lidded eyes inside deep crow's feet reaching to his temples. His are the eyes of a man listening to a fast-talking horse trader. Smile lines etch one cheek.

Billy is a former council member of the Creek tribe. The Alabama Poach Creek tribe received official recognition in 1984 from the Bureau of Indian Affairs, earning access to federal assistance to improve their lot. Roads and sewers, a health clinic and new homes followed recognition and a modest financial settlement. Billy celebrates cautiously, a trait common to many tribesmen wary of the hard fought victories wrestled from the resistant white world. He understands that even progress can dismantle the community. "Hard times held this community together," he stated. "Now we have to find a different kind of glue." The harsh alchemy of poverty and isolation no longer fuse the Creek tribe in Alabama. Prosperity is their new challenge.

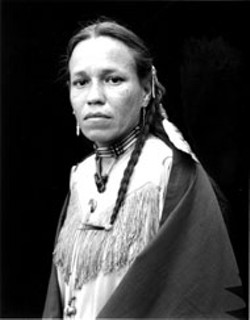

Anna Branham is a teacher and dancer from the Catawba Nation in South Carolina. "My great, great grandmother Sally Gordon spoke only Catawba," she related. "She was one of the last of our people to do so. I want to go out of this world like my great, great grandmother." Anna Branham is the poster woman of this show. She is stoic, proud and resolved, qualities I have long associated with a lifetime infusion of video and photographic images summing up my naive conception of "Indian": Sitting Bull and Tonto and Pocahontas.

Anna Branham has thick black braided hair tied with leather cords, silver earrings and a bead throat collar. She is dressed in a traditional pull over serape, with a V-shaped mantle of strings falling over her buckskinned breastplate. Beads and a single bell dangle from cords pulled through metal buttons from her shoulder and neckline. A feather from her hair disappears behind her shoulder. Her smile line and the turned up edges of her wide mouth upend her stoic gaze into the camera. She has a wide mouth and jaw and a ruddy complexion, her eyes are wide open and slanted down toward the edges of her face over high cheek bones. To my undiscriminating anglo eyes, she is Inuit, Aztec and Cherokee, an amalgamation of culled identities summed to "Indian." She is timeless and classic and indefatigably beautiful.

Gaillard and DeMeritt offer us a glimpse past our own easy and rigid stereotypes. Native Americans are lawyers, students, healers, teachers and artists. They are our neighbors. American Indians suffer the challenges of facing the modern world as do we all, but without the ingrained expectations of entitlement enjoyed by the American first world, and for centuries without the civic presumptions of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.

This show gives us a closer look at one bright thread of our vast cultural tapestry, a bold, abrasive and beautiful thread both disparate and inextricably woven into our collective identity. We can't pull the thread out; we've already tried that. Bleach won't work either. Maybe a little recognition, respect and tolerance might work. Ya think?

The exhibit We're Still Here: American Indians In the South continues through February 13 at the Levine Museum of the New South, 200 E. Seventh St. Call 704-333-1887 for details.

Latest in Feature

More by Scott Lucas

Calendar

-

Derek Hough - Symphony Of Dance @ Ovens Auditorium

-

NEW WINDOW GALLERY-Pat Rhea-ACRYLIC PAINTINGS-April 05-30 2024 VALDESE, NC 28690 @ New Window Gallery/Play It Again Records

- Through April 30, 12 p.m.

-

"Blood Residue Analysis of Paleoamerican Stone Tools in the Carolinas" @ Native American Studies Center

- Fri., April 26, 12-1 p.m.

-

ARTS RENAISSANCE, a GALA supporting the ARTS in South Carolina @ the Columbia Museum of ART

-

The Piano Guys @ Ovens Auditorium

The Piano Guys @ Ovens Auditorium

-

The death of CAST 5

What really happened to Charlotte's beloved experimental theater company?

-

Jessica Moss Makes the Gantt Center a Safe Zone for Local Artists 2

Flipping the script

-

Charlotte ink 7

Behind the pain with a trio of the Queen City's finest tattoo artists