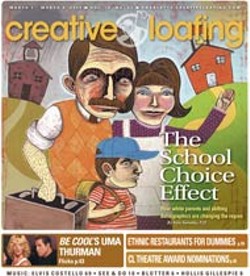

School Choice Consequences

How white parents and shifting demographics are changing the region

To Clark, it was the beginning of a classic spiral he'd seen time and time again in other big urban systems. It had happened in Boston, Cleveland and Detroit. Contrary to popular perceptions of "white flight," Clark knew that white parents didn't have to leave a school system to deal it a crushing blow. Over time, simply not showing up in the first place would do the trick. And that, Clark wrote, was exactly what white parents were doing here.

But Clark's warnings — buried in a report to the court during the 1998 legal battle that ended student school assignment by race — were ultimately lost in an avalanche of legal briefs and scholarly analysis. At the time, white enrollment in CMS was over 50 percent, and the system still had white kids to burn. Urban schools were in shambles, and desperately needed repair. Dealing with concentrations of poverty understandably took precedence over courting suburban parents. That could always be done later.

Problem is, it wasn't. In the process, without ever formally choosing to, the school system contributed to a demographic chain of events that today is radically altering the political and social landscape of Mecklenburg and surrounding counties.

In 2000, just two years after Clark's warning, white student enrollment in CMS dipped slightly below 50 percent for the first time. It was a momentous event that would have sent a chill down the spine of any sociologist or demographer with a school desegregation background. But since we don't have a lot of those around here, the significance was largely lost on local politicians. With almost no fanfare, Charlotte Mecklenburg Schools had hit the tipping point.

Bill McCoy, former director of the UNCC Urban Institute, believes this is the most critical issue the community currently faces, yet no one is leading a charge to deal with it.

"The thing that is missing in this discussion right now is where is the business community on this?" said McCoy. "This is a business town and this school system controversy cannot be a positive factor in terms of business people locating here and people growing businesses here. The business community has to come forward and engage in this discussion and in looking for solutions, because if we continue to go the way we're going, it is going to have a very negative impact on the business community."

"Education sits on top of the economic food chain, and people move to what they perceive to be good education," says Dr. Doug Bachtel, a demographer with the Department of Housing and Consumer Economics at the University of Georgia. "To put your situation in economic development terms, this ain't good."

Bachtel says that middle and upper-middle class parents who move to surrounding counties are often the same types of people who are prone to join PTAs and the Charlotte Chamber of Commerce.

"You begin to lose these folks who can make a difference," explained Bachtel. "That hurts economic development in terms of the labor force and because those are the kinds of people who usually get involved in trying to attract new industry and making their community better. Once that process starts, it is like a snowball and it picks up speed."

The Tipping Point

Since the 1970s, sociologists have been giving people across the country the same test. They hold up flash cards picturing several dozen homes and ask what they'd do if someone of another race bought a home in their neighborhood. Then they add another, and another. For the last few decades, the results have remained largely the same. When African-Americans own 25 percent of the homes nearby, whites begin to get antsy. At 50 percent, a majority of whites say they'd leave or that they wouldn't move into the neighborhood in the first place. For African-Americans, a 50-50 racial mix has been the preferred ideal in this test. But bump their neighborhood up to 75 percent white and they, too, begin to get cold feet.

The same thing applies to schools, say experts.

"Whites will go to schools that are 60 percent white and 40 percent minority," said Clark. "When it gets down below 50-50, they will not go. Whites will just pull out and if new people are moving to the district, they will look at the school structure in the city and say, 'Well, I can live in a neighboring county.'"

Latest in Cover

Calendar

-

NEW WINDOW GALLERY-Pat Rhea-ACRYLIC PAINTINGS-April 05-30 2024 VALDESE, NC 28690 @ New Window Gallery/Play It Again Records

- Through April 30, 12 p.m.

-

TheDiscountCodes

-

"Blood Residue Analysis of Paleoamerican Stone Tools in the Carolinas" @ Native American Studies Center

- Fri., April 26, 12-1 p.m.

-

Brightfire Music and Arts Festival @ GreenLife Family Farms

-

ARTS RENAISSANCE, a GALA supporting the ARTS in South Carolina @ the Columbia Museum of ART

-

5 Online Player Communities to Join in Michigan

-

A beginners guide to online sports betting in the US

-

I Changed my Sex. Now What?

Scott Turner Schofield's rapid transit to a new identity