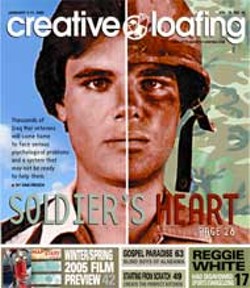

Soldier's Heart

Thousands of Iraq War veterans will come home to face serious psychological problems and a system that may not be ready to help them.

By Dan FroschPage 3 of 6

These same doctors knew they could treat the disorder better than anyone. They have been on the cutting edge of PTSD since its diagnosis was born, from a war whose lessons now seemed distant.

Sergeant Dave Durman did a tour in the Mekong Delta back in 1969. He was 18, and had joined the navy the minute he got his draft notice, even though some of his buddies had already gone and died there. "I think it was because I just really loved the water," Durman says.Durman also loved working on the supply ship where he was stationed and the pulsing adrenaline whenever his unit supported the Marines on missions around the South Vietnamese coast. He loved it all so much that when he came home he stayed in the navy as a salvage diver for nine years and, in 1995, rejoined the military as part of the Virginia National Guard's 1032nd Transportation Company, 10 miles from his home in Kingsport,Tenn.

In February 2003, Durman's unit was sent to Kuwait. He was 52 years old.

Two months later, the 1032nd crossed into Iraq, charged with shipping supplies from the southern city of Talil, 300 miles north to Balad. Other convoys had been attacked on the same route, so Durman and the 19-year-old soldier who rode with him slung their flak jackets protectively over the outside of both truck doors because, Durman says, "you could stab a hole through those doors with a knife."

During one August haul, Durman came upon a group of Iraqi police who had just shot two children for stripping a car on the side of the road. He drove right by their bodies. "We're told not to interfere with domestic affairs," Durman says quietly.

"I didn't want to get personally close to the Iraqis, because I knew we might have to shoot them," he continues. "I'd look into their eyes and they all looked like Gooks."

In September, Durman's unit shipped back to Virginia. It was then the nightmares started, about Iraq, but also things he'd buried -- his abusive childhood, Vietnam.

His girlfriend, Teresa A. McKay, noticed that Durman, once confident and kind, now broke into random sweats and angered easily. He drank too much whiskey and bought a .357 pistol. Their sex life, McKay said, went "190 degrees different."

To McKay, a former nurse who'd worked with homeless Vietnam veterans, Durman's behavior looked disquietingly familiar.

Indeed, Vietnam provides the clinical and historical framework for PTSD and Iraq. Before Vietnam, treatment of a soldier for the psychological effects of battle was not really treatment at all, even though PTSD had long been acknowledged under a variety of names.

In 1871, former Union Army medic J.M. Da Costa wrote about a stress disorder caused by heavy fighting. He called it "Irritable Heart," a name changed shortly thereafter to "Soldier's Heart."

During World War I, according to VA psychiatrist Jonathan Shay, veterans returning home with Soldier's Heart were told by military doctors they had "shell shock," or "combat neurosis."

After World War II, says Shay, when tens of thousands of soldiers were hospitalized with psychiatric problems, doctors diagnosed the majority with paranoid schizophrenia.

"The diagnostic spirit which prevailed was based on Plato's idea that if you had good parentage, good genes, a good education, then no bad things could shake you from the path of virtue," says Shay.

During Vietnam, that Platonic ideal began to shift. In 1970, 20 young vets from the group Vietnam Veterans Against The War (VVAW) asked psychiatrist Robert Jay Lifton to speak with them about the war. The vets didn't trust the VA or the military, but knew they needed to calm the devils they'd brought home.

Lifton, who had studied Hiroshima survivors and been an army psychiatrist, began meeting in New York with the group in what became known as "rap sessions."

He was shocked by the extent of the veterans' traumas.

"These men talked about a particular combat situation that had a level of extremity which was new, even to me," Lifton says.

Prompted by the rap sessions, VVAW opened up dozens of "storefront" counseling centers -- places where Vietnam veterans could speak with other vets about their experiences, a crucial part of treating PTSD.

Still, despite the growing number of vets clearly suffering, the VA wouldn't accept PTSD as a diagnostic entity.

"This was because many of them were talking about atrocities, and that process was associated with a political view of the war," says Lifton.

Latest in Cover

More by Dan Frosch

-

Iraq War Vets Still Underserved

Jul 27, 2005 -

Soldier's Heart II

Mar 9, 2005 -

If Ashcroft Were Uninsured...

Mar 17, 2004 - More »

Calendar

-

NEW WINDOW GALLERY-Pat Rhea-ACRYLIC PAINTINGS-April 05-30 2024 VALDESE, NC 28690 @ New Window Gallery/Play It Again Records

- Through April 30, 12 p.m.

-

TheDiscountCodes

-

"Blood Residue Analysis of Paleoamerican Stone Tools in the Carolinas" @ Native American Studies Center

- Fri., April 26, 12-1 p.m.

-

Brightfire Music and Arts Festival @ GreenLife Family Farms

-

ARTS RENAISSANCE, a GALA supporting the ARTS in South Carolina @ the Columbia Museum of ART

-

5 Online Player Communities to Join in Michigan

-

A beginners guide to online sports betting in the US

-

I Changed my Sex. Now What?

Scott Turner Schofield's rapid transit to a new identity