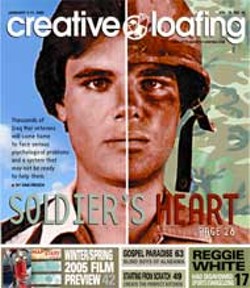

Soldier's Heart

Thousands of Iraq War veterans will come home to face serious psychological problems and a system that may not be ready to help them.

By Dan FroschPage 5 of 6

VA psychologist Scott Murray says many vets won't feel symptoms of PTSD until 15 months from now.

"This early on, PTSD is much higher than anything we've seen in previous conflicts," Murray says. "We anticipate the numbers are only going to keep getting higher."

Psychologist Kaye Baron currently treats some 70 active soldiers and their families in a private practice in Colorado Springs, near Fort Carson. From clinical discussions she's had with soldiers, Baron thinks the PTSD rate could spike as high as 75 percent.

Such a rate, Robert Jay Lifton says, is inexorably tied to the war itself.

"This is a counterinsurgency being fought against an enemy which is hard to identify, and that leads to extraordinary stress," he says.

According to Jonathan Shay, the issue with the most potential for psychological torment is whether soldiers feel they've been led into battle for a noble cause.

Shay, who compared the Vietnam veteran's battle experience to that of Achilles in his book, Achilles in Vietnam: Combat Trauma and The Undoing of Character, wrote how the Greek hero felt betrayed by his arrogant general, Agamemnon, whose disrespect of a priest of Apollo brought down a plague on the Greeks.

"If a soldier has experienced a betrayal of what's right by those in charge, their capacity for social trust can be impaired for the rest of their lives," Shay says.

Indeed, Dave Durman says he first began feeling uncomfortable in Iraq when it became clear there were no WMDs. He says his unit was furious when General Tommy Franks retired mid-war, while the rest of National Guard and Reservists were subject to the Army's "stop-loss" policy, which extends soldiers' deployments.

Walter Padilla and Ron Luker were outraged when they saw Iraqi children playing in human sewage gurgling through the streets while the Army did nothing. "I thought we were here to help these people," Padilla says.

That sense of betrayal translates into what Shay calls "complex PTSD": nightmares, paranoia, violence, self-hatred and a crippling distrust.

Shay, who also compared the Vietnam veteran's homecoming with Odysseus' tortured return to Ithaca in a second book, Odysseus in America: Combat Trauma And The Trials of Homecoming, says that after Vietnam: "Vets were coming home and burning through their social capital. Everything in their life was being destroyed or used up."

Peterson's dream-induced violence, Padilla's bar fights, Durman's drinking, Luker's accusations about his wife are powerful examples of a similar dynamic.

According to the VA, veterans with PTSD are more apt to be jobless, impoverished, homeless, addicted, imprisoned, without a stable family and three times more likely to die before the rest of us.

Many of the soldiers Kaye Baron treats tell her they only want to get far away from their lives at home.

"They just want to go off in the mountains," she says. "And be by themselves."

Since reporting on this story began in October, Joshua Peterson and Dave Durman have started therapy at the VA. They're likely getting some of the most advanced care in the world. They're also lucky. Peterson's mother-in-law knows a VA psychiatrist, and Durman was already enrolled, thanks to his time in the Navy. Meanwhile, Walter Padilla is trying to leave the military and says he'll get help once out. Ron Luker is still in Iraq and Crystal Luker says she'll drag her husband to the VA if she has to.

These soldiers won't be alone. So far, more than 10,000 veterans from Iraq and Afghanistan have sought psychological help from the VA, and there's every indication the numbers will jump significantly.

Despite the challenges these numbers predict, Harold Kudler, co-chair of the VA's PTSD Committee, says: "We've never been so prepared," and points to unprecedented cooperation with the Department of Defense, intensified PTSD outreach and the 206 vet centers.

Anthony Taylor, the Vietnam vet who runs Bay Pines' PTSD program, knows that the need for treatment will remain long after the Iraq conflict is over.

"The war doesn't stop when they say ceasefire. You don't forget what it's like to pick up body parts." And he's confident that vets will continue to trust Bay Pines as a resource, despite recent controversies surrounding the $265 million CORE-FLS computer system which the VA tested unsuccessfully at the hospital. "We have a good reputation with PTSD vets, and they can separate that from the CORE- FLS stuff."

But neither reputation nor preparation can make up for lack of funds. "You can only provide the services for which you have the resources," says VA psychologist Scott Murray. "There has to be significant improvement in an allocation of funds to make that occur."

On Nov. 20, Congress added $1 billion to the Bush Administration's $27.1 billion VA health care budget for 2005. The amount fell $1.5 billion short of what was recommended by the House Veterans Affairs Committee. And while Congress earmarked an additional $15 million for PTSD, few think that money will make much difference.

Latest in Cover

More by Dan Frosch

-

Iraq War Vets Still Underserved

Jul 27, 2005 -

Soldier's Heart II

Mar 9, 2005 -

If Ashcroft Were Uninsured...

Mar 17, 2004 - More »

Calendar

-

Wine & Paint @ Blackfinn Ameripub- Ballantyne

-

Queen Charlotte Fair @ Route 29 Pavilion

-

NEW WINDOW GALLERY-Pat Rhea-ACRYLIC PAINTINGS-April 05-30 2024 VALDESE, NC 28690 @ New Window Gallery/Play It Again Records

- Through April 30, 12 p.m.

-

TheDiscountCodes

-

Face to Face Foundation Gala @ The Revelry North End

-

Esports in Charlotte Takes Off: A Guide to Virtual Competitions and Betting

-

Homer's night on the town 41

If you drank a shot with the Knights mascot on Sept. 20, you were basically harboring a fugitive

-

Beauty Industry Trends To Look Out For In Charlotte In 2022