"I'm gonna do this again."

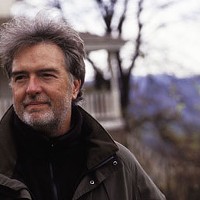

Robert Osborne, the 75-year-old host of Turner Classic Movies, takes a few steps back on the living-room set of Studio C, nestled inside Turner Broadcasting's Techwood Avenue complex. He's having a hard time wrapping his lips around the name of the 1966 western Alvarez Kelly, directed by Edward Dmytryk and starring William Holden and Richard Widmark.

It's the "Alvarez" part that keeps tripping him up, and he knows it. The monotone suggestion "Slow it down" comes over a speaker from director of studio production Sean Cameron. They're longtime collaborators, and it's a long workday. They both know verbal gaffes come with the territory. Over five days during Osborne's monthly visit to Atlanta from his home base in New York City, they need to knock out 280 two-minute intro and conclusion segments for 140 movies.

In a minute, an assistant who's been with Osborne for seven years hustles onto the set to touch up his feathery silver hair and to adjust his tie, while Osborne takes a sip of hot water from a TCM coffee mug. There are times, he admits, when he just can't get into a rhythm.

"I can tell the minute I get out of bed if it's going to be a good day or not," he says offstage later. "Sometimes even my head will be clear and I get out of bed and it's just clouded. Or the mouth doesn't work sometimes, or sometimes you get phlegm in your throat."

Osborne finally nails "Alvarez" on his third try and gets back into a groove. In just a few minutes he delivers a Trivial Pursuit round's worth of movie nuggets. It all flows naturally from Osborne's light, measured baritone -- that the 1927 silent Wings, which debuted as part of TCM's monthlong "31 Days of Oscar" programming, was the first movie to win an Academy Award and was one of Gary Cooper's first major roles; that the 1933 Busby Berkeley-choreographed musical 42nd Street featured the debut of Ruby Keeler; that the 1948 Powell-Pressburger musical The Red Shoes inspired a generation of young ballet dancers; and that the 1954 sea drama The Caine Mutiny required protracted negotiations with the U.S. Navy to guarantee its cooperation.

So it goes with Robert Osborne, whose trademark segue in between movies, "Up next," is as familiar as the trivia he mines with TCM staffers. Though his once-settled network underwent a rare corporate shake-up last year, he remains a fixture: the tenured professor in Turner Classic Movies' film school of uncut and commercial-free presentations.

"31 Days of Oscar" is Osborne and Turner Classic Movies at their best. The series highlights 350 Oscar-winning and -nominated works from inside and outside the Turner vault, famously made formidable back in 1986 when Ted Turner purchased MGM/UA Entertainment Co. (Turner eventually sold to TimeWarner, and left the merged company's board two years ago.)

To show off the vault and TCM's licensing prowess, viewers in an estimated 75 million homes this year are given two sets of themed programming: Daytime features movies by genre, while evenings present movies by the decade. And the network is introducing 35 new titles, including movies as old as 1927's Wings and as recent as 2003's The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King.

As usual, Osborne is spotted on weekend afternoons by the Los Angeles-based Ben Mankiewicz, scion of a movie-making clan. But Osborne is so associated with TCM that it's difficult to think of another personality who so clearly defines a network. "I can be Walter Cronkite!" he jokes.

TCM's popular programming and website, paired with Osborne's steady, high profile, overshadows an unprecedented year of upheaval, which saw the elimination of almost an entire level of upper and middle management. Turner executives primarily responsible for larger networks such as TNT and TBS assumed some of those roles, with others going to remaining TCM employees, as the more autonomous network is tucked more snugly into the broader corporate structure. The goal, according to new management, is to leverage TCM's revenue stream by working more closely with the other networks, which in recent years underwent their own "brand" overhauls.

"If you said to me, 'Make this into a multibillion-dollar business to compete with TNT,' that's impossible," says Steve Koonin, who, as Turner Entertainment Group's president, assumed control over TCM last spring. "That's not [TCM's] role. And that's why it had to be tucked into a portfolio and not be on an island -- because it has big brothers and big sisters to help grow it and protect it."

What that means for Turner Classic Movies and its longtime host could be the 75-million-home question. Just how broadly can they expand the "brand" without diminishing the quality?

Regardless of how that question is answered, there is the ever-steady Osborne, who has built a career out of his poise, preparation and personality. He believes in his company, his movies, his mission and his audience, and is in it for however long he can be.

"It's been great for me," he says after taping his segments. "I've been very lucky here, and also with my job at the Hollywood Reporter" -- where he's been a columnist since 1982 -- "in that I'm part of the package but I'm not in any corporation, and I understand how that works. Here I kind of work in my own unit. So I don't get into all that kind of stuff. I realize in any kind of corporation that's going to happen, but I'm lucky in that I don't have to get involved with that."

Robert Osborne is the last of a dying breed, a once-aspiring actor who turned into a Hollywood insider and historian -- an authority but a friend, a public face revered in private. He's always seemed to be in the right place at the right time, and if luck is when preparation meets opportunity, Osborne has prepared with the charm and knowledge to move up in a business swimming with sharks.

He talks about his career like he does movies, never making a cinematic reference without context. He mentions his Seattle stage work after graduating from the University of Washington with a journalism degree and recalls landing a role in a 1958 production: "The actor I was doing the play with was Jane Darwell, who'd won the Academy Award for playing Henry Fonda's mother in The Grapes of Wrath. And she said, 'You should come to California.' I could stay at her family's house, and I had some friends there."

His run of luck came in succession. He scored a six-month studio contract with 20th Century Fox -- easy to get back then, he says -- and started taking acting classes.

"Paul Henreid, who played opposite Bette Davis in Now, Voyager, came to visit a friend who was giving the class," Osborne recalls. "And he saw me, and he said, 'You know, I'm doing a TV western called "The Californians," and I'm directing an episode, and you'd be right for the guy for it."

The studio that owned the show, Desilu, was run by Lucille Ball and her husband, Desi Arnaz. He wound up being an assistant to Ball while trying to get his acting career going. She was more impressed with Osborne's curiosity and knowledge of movies and actors than his acting talent.

"She was fascinated by the fact that I was staying at Jane Darwell's house, because Lucy loved all the character actors she worked with. She was fascinated with the Edward Everett Hortons and the Donald Meeks, and those guys. ... She was fascinated that I knew who they all were. So that's kind of what attracted her attention to me, was my attention to old movies."

While Arnaz was off on his various extramarital affairs, Osborne says, Ball often turned her mansion into a repertory movie theater, inviting Osborne and his friends over to watch old movies and talk about the stars. Back then, there was no concept of "classic cinema" -- new movies opened, played and closed, never to be shown again.

"They were all [film] buffs like me," Osborne says, "and we all had these 16 mm projectors, and we had no money, but you'd borrow a print from somebody or somebody had a print, or you would get to know someone at a TV station who had a print and lend it to you for the weekend. And then you'd gather your friends together, and you'd pool your money together, and get some spaghetti and wine and watch these old movies.

"I had a friend who was a dancer in one of Ginger Rogers' nightclub acts ... and he'd show a movie and he'd get Ginger to come over to watch with us, and she would talk about how they did this or how they did that," Osborne continues. "These people loved us because we knew who they were and we cared who they were and we cared about the process."

Osborne's acting career lagged. He may be best remembered for a spot in "The Beverly Hillbillies'" 1962 pilot episode. Ball warned Osborne that a nice Midwesterner like him couldn't hang with the cutthroat New York actors in Hollywood. ("There'd be this part for a TV show that I'd go read for, and I'd say, 'Well, George Peppard would be much better for this part!' The completely wrong attitude.")

She encouraged him to match his journalism degree with his encyclopedic movie knowledge. Write a book, she said. Even if it's not good, it'll be impressive at a job interview. And so Osborne wrote a book on the Oscars that was unique in its inclusion not just of winners but also the nominees.

If a star went to the hospital, TV stations would ask Osborne to appear and provide a career overview for the evening news. And no matter how many stars he met, he never seemed starstruck.

"I could watch Lana Turner arrive at a premiere and be so impressed because it was like, 'Oh my God, this great star is coming to a premiere.' And then I could have dinner with her the next night, and I wouldn't mix the two up."

After Turner Classic Movies launched in 1994, a task force was established to find someone who could host the prime-time lineup. At the time, Osborne was being courted by the dominant American Movie Classics for a daytime hosting job.

But, according to former TCM executive vice president and GM Tom Karsch, TCM offered something else: "Yes, to be in fewer homes, but it was to host movies he cherished -- and to be in prime time instead of daytime."

Karsch remembered Osborne from back in the 1980s, when Karsch worked for Showtime and Osborne at Showtime's sister network, The Movie Channel. "We even shared the same hairstylist," Karsch recalls over coffee. Karsch, who'd joined TCM within its first year, thought it was a perfect move.

"Robert is incredibly warm, incredibly gracious," says Karsch, who left TCM last spring when Koonin added TCM to his duties. "Any stranger that comes up to him, and you can imagine how many people come up to him with all sorts of oddball trivia or anecdotes, he treats everyone like they're very important people. When you come across a person like that, you want to jump on him. Ann Miller once said during an interview with him, 'You know my career more than I do!'"

Armed with Osborne's cache and Ted Turner's MGM/UA library, TCM went after AMC, and after some initial struggles caught up with the network in cable subscription. By late 2002, AMC had stopped trying to compete in the classics market, started adding commercials and now focuses on original programming such as the Golden Globe-winning "Mad Men."

But one thing AMC never had was Osborne, with his connections as a columnist and with the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences; while he's been the official greeter at the Oscar ceremonies' red carpet only recently, Osborne has produced an updated coffee-table book on the awards for the past two decades since the 1980s. His next update, 80 Years of the Oscar: The Official History of the Academy Awards, is due out on Abbeville Press in September.

He has become synonymous with Oscars, and the movies, and AMC was never able to top that.

"There's a casualness to Robert," Karsch notes. "The attempt by the network from the very beginning ... there already was AMC, which had positioned itself as nostalgic, like going to the Fox Theatre with all that red velour ... so when we launched we said, 'We'll be the hip guys. We're going to do this in a way that doesn't turn off an older person. We're going to do it with a freshness, like a club that you want to be a member.'"

Steve Koonin is known for thinking big when it comes to branding. This is the man who, near the end of his tenure at Coca-Cola, wanted to celebrate the new millennium by projecting the Coke logo via laser to the moon.

Over his years at Turner, Koonin helped oversee the successful rebranding of TNT as the drama network and TBS as the comedy network. After he was named president of Turner Entertainment Group last year, Koonin turned CourtTV into TruTV and the local Atlanta station TBS into Peachtree TV. Turner Broadcasting CEO Phil Kent added TCM to Koonin's duties, which sparked a departure of some top TCM executives. Koonin won't go into details about the exodus. But as someone who had to deal with similar corporate shake-ups at Coke "on a weekly basis," he saw the change as a necessary business move.

"I don't think it's appropriate to talk about why we made contraction decisions," says Koonin, who adds that he saw "redundancies" in TCM management. "How many senior marketing folks do you need? How many senior on-air people do you need? The reason we constantly work with people and develop people is so they can work on a multitude of brands.

"I don't think that there's been substantive management changes," Koonin continues. "One or two. I don't think it's substantive in a world of 60-plus employees."

Within a few weeks, Karsch, the head of TCM since 1995, was gone. So were Katherine Evans, senior vice president for marketing and enterprises; Shannon Davis, senior vice president for on-air packaging and original programming; and Chris Merrifield, vice president and creative director for TCM on-air creative.

The change basically meant going from more of a vertical management structure to a horizontal one, with other Turner executives adding TCM to their duties and TCM executives adding assignments at other Turner networks to their duties.

As an example of this new structure, Koonin points to Jonathan Karron, who went from being TCM's director of marketing to vice president of digital marketing for TBS, TNT and TCM. "We saw that there was opportunity to give people broader exposure. ... You can learn best practices from each one."

At Turner, like with most networks, it's all about strengthening the "brand," and the network is contemplating several strategies to do this. The term in vogue is "brands without borders," which is in keeping with a push to make the networks function more in concert with one another.

Before, TCM operated more independently of the other networks. But under Steve Koonin's leadership, the desire is to bring TCM more in line with the others, which includes cross promotion.

"Around Christmas we did an e-commerce spot on TNT promoting TCM products," says Molly Battin, the senior VP in charge of brand development and digital platforms. "And we saw a spike in our sales."

While the network may have lost some of its management and veteran creative energy, there seems to be faith that those who remain will maintain TCM's level of quality. You can see it in Osborne but also in the one-two programming punch of senior VP for programming Charlie Tabesh and VP of original productions Tom Brown.

"The great comfort I have not being at the company anymore is knowing that people like Charlie [Tabesh] are still carrying the torch," Karsch says.

Tabesh, who's been with TCM since 1998, oversees the programming from a library of 5,000 titles. About 40 percent of movies shown on TCM come from the Turner library, with the rest coming from licensing arrangements with other libraries. The complicated arrangements are based on factors such as how many titles are needed and for how long.

On more challenging projects such as the "Race and Hollywood" series, which addresses racial stereotypes, TCM lines up academics and film figures to introduce movies that speak to them.

Tabesh also works in concert with Brown to pair documentaries of film legends with themed programming of movies that celebrate their work. Among those is last year's three-hour, Emmy-nominated Brando. And last month, the network featured the Martin Scorsese-narrated documentary, Val Lewton: The Man in the Shadows, a partnership of TCM, Scorsese (a huge Lewton fan) and writer/director Kent Jones.

The documentary kicked off a 10-film series by the horror master including The Cat People and I Walked with a Zombie. TCM also added the doc to sister company Warner Home Video's re-release of its Lewton box set. "There have been people like Clint Eastwood or Martin Scorsese with a project they knew no other network would do, but also, we don't have that budget," Brown says. "Val Lewton was [Scorsese's] passion project. We were intrigued ... this was a producer who was very influential in Hollywood but one the average movie-goer didn't know about."

Future original programming projects include a Race and Hollywood series focusing on Asian figures in American movies, as well as a serialized version of the special Under the Influence, in which film critic Elvis Mitchell interviews actors and directors about movies that influenced their work.

The financial stakes of all the new deals and partnerships are high, especially considering that the network is already in more than 90 percent of the cable homes it can be in. Those cable-operator license fees, which Variety projects will climb past $200 million in 2008, have a ceiling.

So Koonin is looking for other ways to make more money. If there's one thing management is most proud of, it's the increased revenue generated from book and DVD sales. Part of the jump has come from its partnerships with Warner Home Video and the home-entertainment warehouse Movies Unlimited.

With the TCM name on a movie almost instantly offering a seal of approval, sales doubled last year from $2 million in 2006 to $4 million. The network scored another coup with its promotion of an 800-page DVD catalog (priced at $15 with shipping), which sold 30,000 copies and led to more DVD sales.

"It speaks to classic fans," says Richard Steiner, VP for new media/interactive. "They love to have something physical in their hands that speaks to classic film, the ones who like to have it and see it. It represents a collector's element, and it helps you add to your collection."

So there's a push to drive more people to a website that already draws more than 1 million unique visitors a month, and which is flush with DVDs and other merchandise.

"The need is to cultivate that passionate fan base and to create and utilize and build a community with those folks," Koonin explains. "And if that's a community that supports you in DVD sales, if it's a community that supports you in festivals, if it's a community that supports you online, if it's a community that's going to support you if you have a branded product, that idea is to take that share of mind, and that share of heart, and develop it into a share of wallet."

Other changes include TCM's on-air talent. Take the "Guest Programmer" series. Osborne says the series -- traditionally an occasional program -- was inspired from his conversations with everyone from people on the street to conversations with friends on what TCM should program.

In November, the network spent the entire month of evenings using guest programmers, including nonfilm-related figures such as Donald Trump and Atlanta's own Alton Brown of the Food Network.

Rose McGowan, recent star of the movie Grindhouse, whose now-defunct WB series "Charmed" runs in syndication on TNT, impressed executives so much as a guest programmer that they decided to hire the 34-year-old for "The Essentials." The program is used to entice the average viewer to appreciate classic cinema. After allowing directors Sydney Pollack, Rob Reiner and Peter Bogdanovich to host solo, TCM decided to pair Osborne with a woman (first film historian Molly Haskell and then actress/author Carrie Fisher). McGowan debuts with Osborne on "The Essentials" March 8.

"Rose McGowan ... is young and pretty, which doesn't hurt," Tabesh says. "But she's such a fan. We wanted to use somebody who legitimately loves the movies, not just putting on a pretty face that doesn't fit. She was so good [with "Guest Programmer"], she talked about movies with such knowledge and passion, and she was such a great contrast to Robert."

Maybe the best and worst thing that could have happened to Turner Classic Movies was AMC's departure from the commercial-free format. Whenever TCM shows a movie from within the last 20 years, the website's message board lights up.

This year, Tabesh hatched the dual-theme idea of featuring movies by genre by day and by decade at night -- which, due to timing, meant more than a few movies from the past 17 years showing up over the weekends. So when a movie as recent as 2003's The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King -- which is often shown on TNT -- shows up as part of "31 Days of Oscars," Tabesh braces for an inevitable backlash.

"There are some people who watch the network constantly and some get grumpy about watching some of the newer ones, and think we're becoming more like AMC," he says.

But network executives seem content to trade some criticism for showing more recent, more accessible and less pedigreed Oscar winners. "There's no goal of introducing more contemporary movies this year," Tabesh says, "but the goal is to showcase the history of the Academy Awards. ... Some people definitely freak out when they see a movie from the '90s. We're still living with this ... from when AMC shifted their format. Everyone is still on edge from that. [Viewers are still] scarred by that and feel that any movie that we play from the '80s and '90s, it's, 'Oh my God, they're going the way of AMC, and they're going to add commercials,' which is not at all true."

The push to broaden the network's appeal risks turning off some TCM loyalists. The seven-year-old Young Film Composers Competition, in which five finalists score a 90-second segment from a silent-film classic, underscored the network's commitment both to silent-film preservation and encouraging young artists.

The winner gets to score the entire film. Last year's winner, James Schafer, provided the score for 1924's Beau Brummel, which was aired on TCM last month. But the project has been shelved while the network tries to "evaluate the program." That hasn't sat well with some fans.

"I think it's pretty unfair of TCM to suddenly cancel the competition when so many of you talented composers were looking forward to entering," wrote one poster on the message board. "Always thought this was a great opportunity for those with such a talent and interest in silent films to contribute to and also inspire more interest in some classic films."

Koonin, who notes the response on the message board is limited to 18 comments, believes the value of the program is limited and wants to consider other potential projects.

"Well, right now we were disappointed in how narrow the scope of it was," Koonin says. " ... Nor had it hit on the brand elements that you'd want to put in a Turner Classic Movies. So we completed it, but we're evaluating whether to bring it back and see what the call for it is. Young Film Composers is asking a very narrow group of demographics to do a very specific task, and there are a lot of other things that we can do with the brand and that we are doing with the brand that I can't talk about today that are much larger in scope than this."

Amid the personnel shuffles, new lines of business and programming changes, one thing is constant: Osborne. His stature in the movie business is cemented -- literally. He earned a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in 2006, and this past December was given the William K. Everson Film History Award by the National Board of Review.

Even at his age, Osborne remains a part of the network's long-range plans, insists Koonin, who will renegotiate his contract extension this year. "Whether it was a man half his age, they couldn't do as good a job as he does," Koonin says. "We have every intention to renew him for as long as he wants to be with the network."

Even out of makeup, he could pass for 65, lines and all. He seems to pace himself in everything he does or says. "I would love to keep doing it as long as it's still viable for Turner," Osborne says. "There obviously will come an age when you're too old to be doing it, I guess, but I'd love to keep doing it. I feel good, and I love the people I work with. And I love this product."

This isn't his only Georgia gig. Each April, he hosts Robert Osborne's Classic Film Festival at the Classic Center in Athens. University of Georgia journalism professor Nate Kohn conceived the idea in 2005 after doing something similar with Roger Ebert up at his previous stop, the University of Illinois. From April 10-12, the pair will present eight classics, starting with Young Frankenstein and concluding with The King and I. "I've thought, 'It's so great to have TCM to show all these great films,'" Osborne says, "but how fun would it be to take these movies ... and show them on a big screen?"

For a man who once pondered an acting career where youth is everything, Osborne has put his years and knowledge to perfect use. Even with the network keeping an eye on younger viewers, Osborne remains unfazed. "I've thought of myself as making choices as to how it would affect TCM," he says, "but I've made choices like that all my life. My dad was a high school principal and a superintendent in this small town I grew up in. There were certain things I wanted to do that I knew I shouldn't because it would reflect badly on my dad.

"So I was not a problem child, but I never felt I needed to rebel because everybody always gave me a lot of space, and kind of let me do what I wanted to do. But all I wanted to do was go to the movies."

This article originally appeared in the Atlanta Creative Loafing.