The People Left Behind

Supreme Court's reversal of "mandatory minimums" too late for some

By Nate BlakesleePage 2 of 3

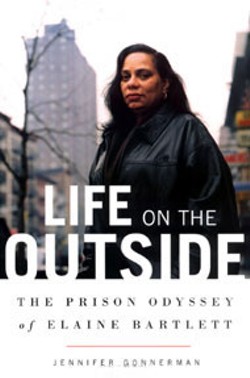

For two and a half years, Gonnerman, a writer at the Village Voice, covered Bartlett's efforts at rebuilding a life for herself and her family. Gov. George Pataki commuted Bartlett's sentence after her case was taken up by the anti-Rockefeller drug law movement in New York and she became something of a minor celebrity. From her first day out, however, it was clear that Pataki's pardon would not bring a happy ending to Elaine's story.

As the news cameras rolled, she was met at the prison gates by her beloved son Apache. Just a boy when she was locked up, he was now 26 and had become the de facto head of the Bartlett household, following the death of Elaine's mother Yvonne. Bartlett's younger son Jamel was locked up for heroin dealing. Her 19-year-old daughter Satara was mysteriously absent. The camera crew followed Elaine to a celebratory dinner, and then back to the apartment in which her kids had grown up in her absence. When she saw what was inside, unmistakable evidence of the mess that her children's lives had become, she told the crew to turn the camera off. Nobody needed to see this.

Except they did need to see it, which is the genius of Gonnerman's project and the reason the book was nominated for the 2004 National Book Award. Elaine's children were living in squalor. When Elaine, and later Elaine's mother Yvonne, was in charge, order and a sense of family pride had prevailed at the Bartlett household. Now everybody seemed to have given up, as Elaine put it.

Her youngest daughter Danae, a high school student, had gone to live with another family, stopping by the apartment only occasionally. Her older daughter, Satara, had dropped out of high school after becoming pregnant. The despondent, non-responsive single mother was nothing like the bright, bouncy girl Elaine remembered. Elaine's younger sister Sabrina, addicted to crack and HIV positive, had also moved in. She watched soaps all day and slept in the living room. Her presence had forced the apartment's other residents to install locks on their bedroom doors. Sabrina's 21-year-old daughter, who had an infant of her own, was also living in the cramped apartment. Elaine had to share a tiny bedroom with Satara and her daughter.

Elaine's daughters, unaccustomed to having a firm parental presence in their lives, quickly came to consider their mother part of the problem. Danae, a rebellious teenager in trouble at school, and, Elaine was surprised to discover, a lesbian, rejected her mother's overtures to rejoin the family. After a shouting match over living arrangements in the cramped apartment, somebody, either Satara or her boyfriend, called the police on Elaine. Though her sentence had been commuted, she was still on parole, meaning she could be sent back to prison at any time if she violated any of a laundry list of rules. Getting arrested, obviously, would likely be disastrous.

Elaine had spent 16 years worrying about her children, dreaming of the day she would be reunited with them. Now she found that — despite all the visiting room chats and letters over the years — she had been kept in the dark about what was really happening to her family. Her daughters were depressed, bitter people, and she did not know them. They blamed her, it seemed, for being gone so long. Elaine's own sisters seemed to blame her as well, for refusing to take the plea bargain, for being gone when their mother died, for saddling them with her four children to raise on top of their own. Her son Jamel was a gang-banger and a drug dealer who had earned the nickname "Murder Mel." Everyone knew it was only a matter of time before he would go to prison himself. Only Apache, who had found his calling coaching youth basketball, seemed to have his life together.

Elaine's efforts to find a new, larger apartment for her family went nowhere. Elaine was told to move into a shelter if she wanted to be bumped to the head of a waiting list. In the end, feeling unwelcome in her own house, she did just that, packing up her things and heading to a YMCA.

Her hunt for a job was equally frustrating. Friends of her son Mel, fellow drug dealers, helped her out with cash at first, but after two months of a fruitless job search she was dead broke and desperate. Elaine attended the mandatory how-to-get-a-job classes required by her parole officer. Most of her fellow classmates — all ex-cons like her — were looking at a bleak future of cashiering at McDonald's or janitorial work.

Speaking of News_feature.html

-

When HIV comes home

Jul 20, 2005 -

Rasslin' Pioneers

Jul 13, 2005 -

Geddings on McCrory: "This guy is vulnerable"

Jul 6, 2005 - More »

Latest in News Feature

Calendar

-

NEW WINDOW GALLERY-Pat Rhea-ACRYLIC PAINTINGS-April 05-30 2024 VALDESE, NC 28690 @ New Window Gallery/Play It Again Records

- Through April 30, 12 p.m.

-

TheDiscountCodes

-

"Blood Residue Analysis of Paleoamerican Stone Tools in the Carolinas" @ Native American Studies Center

- Fri., April 26, 12-1 p.m.

-

Brightfire Music and Arts Festival @ GreenLife Family Farms

-

ARTS RENAISSANCE, a GALA supporting the ARTS in South Carolina @ the Columbia Museum of ART

-

Let your Fingers do the Shopping

Weird, wonderful and just plain useless gifts

-

5 Online Player Communities to Join in Michigan

-

The 10 Scariest People In Charlotte 1