Trouble in mind: The hard truths of Thornton Dial

The artist didn't call his work art until others did. Now you can see it at the Mint.

By Scott Lucas"Life's been tough with me, how's it been with you?" – Thornton Dial

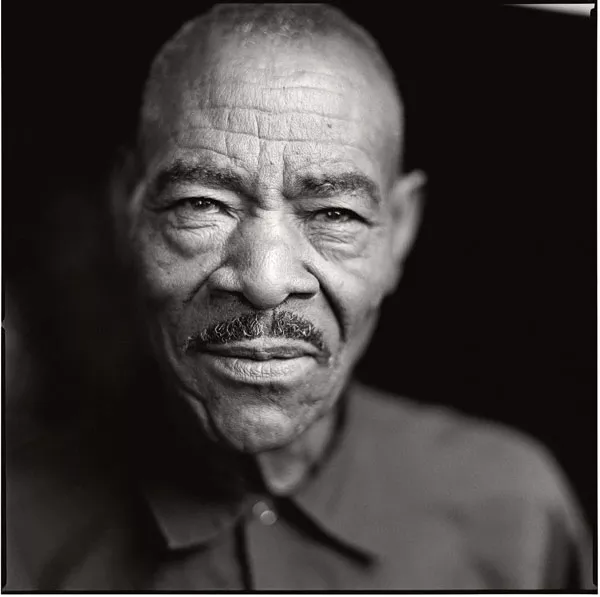

Thornton Dial is 83 years old. He managed to get through his first 60 years without fame or fortune or a host of interested white people. About 25 years ago, Mr. Dial was visited at his home in Bessemer, Ala., by a man named Bill Arnett, an art collector and advocate for Southern black artists. Particularly undiscovered or under-recognized Southern black artists. He liked what he saw in Mr. Dial's yard and workshop.

Arnett's arrival, advocacy for, and eventual friendship with the artist launched exposure of Dial's extraordinary talent to a much wider world, and also unintentionally opened up a new world of hurt for Dial. As the artist's star rose — predictably, as any set of eyes connected to functioning frontal lobes might guess — trouble came brewing from the folks at 60 Minutes.

In 1993, concurrent with two inaugural New York shows including Dial's work, 60 Minutes aired an "exposé" on shady dealings in the "folk" or "outsider" art world. Arnett and Dial were guests; neither expected the broadside Morley Safer delivered. The TV reporter cast Arnett as an opportunistic and manipulative art dealer, and Dial as one of the clueless dupes. The portrayals were inaccurate and unjust, but the damage done.

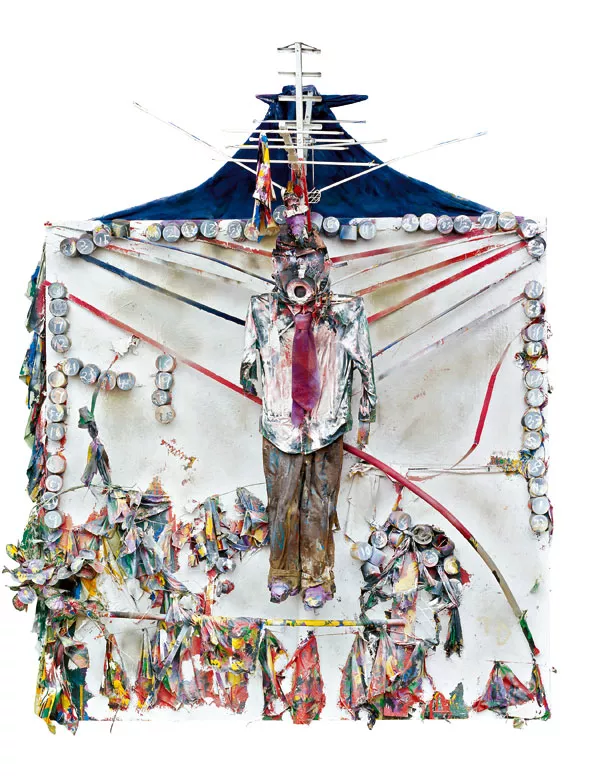

Safer's prime-time beatdown was unwarranted and it left Dial with long-lasting bruises — professionally, financially and emotionally. Dial still had the incident on his mind 10 years later when he hanged himself in effigy in his painting "Strange Fruit: Channel 42, 2003." That painting hangs in the Mint Museum today, and it is a sharp reminder of how deep a wound mere words can leave, particularly if the words are cast from a high spot to a wide audience.

"Strange Fruit" is about as graphically angry as Dial gets. His visual stories typically recount what happens on the outside of his skin; here, he gets unusually personal. A white canvas shroud is draped behind the dead man. A steel post runs behind him supporting an old fashioned skeletal TV antenna; a red scarf serves as a noose. Except for the donut-sized "O" planted in the man's mouth, making him appear surprised, gravity rules: legs, shoulders, eyelids all reach for the red dirt. His striped green shirt is tinged pink, his pants are rolled at the cuff, he sports a purple tie. He's all dressed up for his dressing down. The sad minstrel provides a spectacle moment for the folks in the manor house.

THE DISS ON 60 Minutes was painful, but it isn't as though Dial hasn't seen worse. Dial was born into poverty in rural Alabama on the eve of the Great Depression; he began tending animals and working fields at 6, and labored with his hands for 50 years in the hot- and cold-running inhospitality of the Deep South's racially charged battleground. Life was tough. But it's hard to put a strong man down, and near impossible to keep him there. Dial rose.

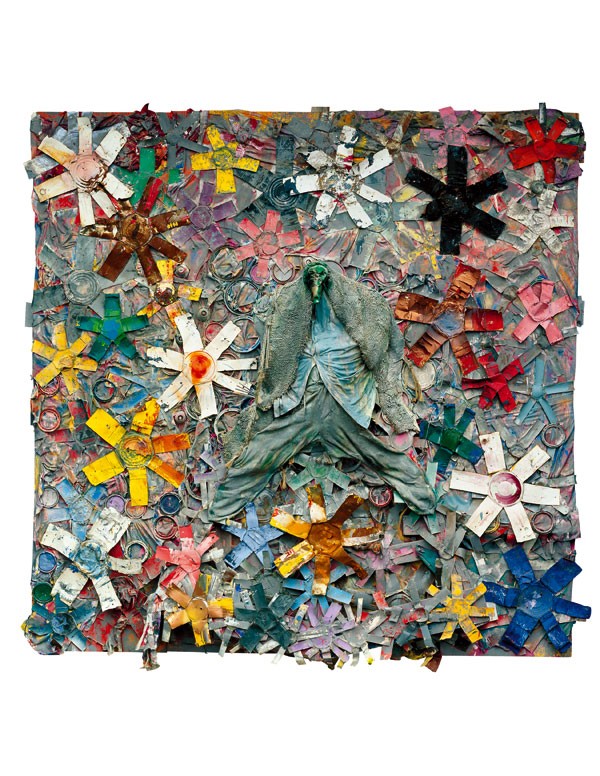

Hard Truths is a retrospective of Dial's most recent 20 years of making art. He has made art since he was a child, but only started calling it art when others did. He occasionally calls the artwork his "things." He makes things. A lot of people make a lot of things, but the things Dial makes can stop a conversation mid-sentence, seize and enthrall you for long moments, set you thinking and feeling and staring for many moments more. Not many people's "things" can do that.

All of Dial's work is monumental in size and spirit, and often, but not always, in message. Working 30 years for a Pullman train car company in Bessemer, the man grew accustomed to working big. Dial is a man, by all the accounts I have read and witnessed on video, who possesses a quiet confidence tempered by a clear vision and blunt honesty. His spirit is embedded in his work as intractably as those deep creases across his brow.

And the message? His few words and his many works attest to a man given to frequently wrestling with human dilemmas big and small. His ruminations run through his fingers and into his work like a 10-ton freight train on a winding downhill run. Subtlety is not the man's strong suit. His work is monumental because he likes it monumental.

"The Old Water, 2004" is a raft of steel, wood scraps, bent iron railing, barbed wire, cloth and carpet scraps. The dark hulk floats across the gallery floor on a thin white pedestal. The vessel lists to the left as if leaning in a tide; it is festooned with creatures — indignant bloody birds of prey, serpents, fish, and one starved and twisted crocodile.

The rough wood and iron and carpet are splotched dark shades of blue, green and grey, appearing camouflaged, a raft rigged for night travel through a forested swamp. An American eagle spreads wings over the vessel from stem to stern. Her wings are wrapped in barbed wire. Vultures perch at bow and stern, patiently waiting for something to die. Where is the hard, dark truth here?

Hold on. Whatever allegory or symbolism may be here, and it is here, is secondary. What welds your feet stock-still to the museum floor is the impact of the piece. It is dark and powerful and beautiful. That's primary, and it's true of almost all the work here. All the work is mostly dark, and mostly beautiful, and always powerful.

After reasonable moments of gawking, we return to the questions "What is that?" and "Why did he paint it all black, and cover it with welded wire mesh, and nail lattice to one side?" and we must ask ourselves the interminable, implacable "What does it mean?"

Those questions will come to us here. Those questions seldom rush to the fore when I see a still life or portrait or pastoral landscape, but they do when I see depictions of abandoned kids, starving animals or landscapes strafed by strip mining. They do when I'm eyeballing any hard truth. We're vexed to hard questions when we're in the presence of profundity — the good and the wicked. And even if these works by this (formerly) poor, (formally) uneducated black man from Alabama are not profound, they sure feel that way.

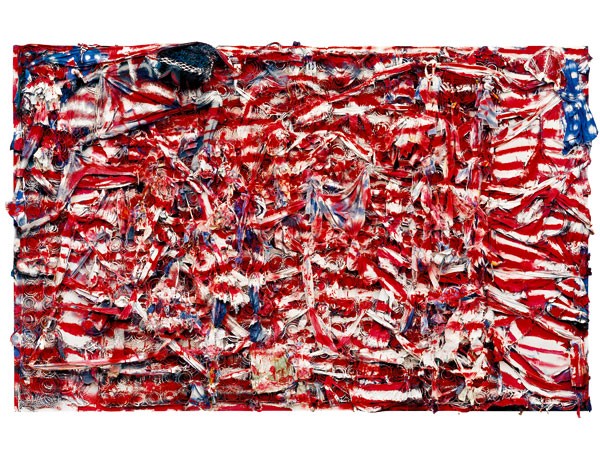

All the works in Hard Truths are accompanied by wall notes that include the title of the piece, the date, materials, the owner of the piece, and a little insight into the genesis and/or meaning behind the work, such as: "This wall assemblage is one of over a dozen Dial created after the 9/11 tragedy." The notes can serve as indicators for determining what the artist had in his head as he worked on the piece. I don't know if the writers of these notes gleaned the information from the artist, from third-party sources, or if they're just speculating on the evidence at hand. I like to read the notes after letting the work soak in and allowing my own interpretation to well up. If nothing of substance wells up and I'm left with "What the hell is this?" I use the writing on the wall as a cheat sheet.

DIAL LIKES to comment on the way folks treat each other, and how the world of money and position and material differences can stretch the divide between rich and poor, black and white. He speaks to that class friction with "Everybody's Welcome in Peckerwood City, 2005."

Eight blue windows frame a white door with white trim. The mock-up of the home façade stands perpendicular to the museum wall. The piece is large — maybe 7 feet x 7 feet — but looks small trying to be a house. Painted gold patches peek through the white trim surrounding the door. The place looks cozy. Two roses, stems twined together, embellish the welcome mat in front of the door. Metal grating stands at the door's threshold behind the welcome mat, and blood runs out from under the sidelight adjacent the door. Maybe not so cozy. This is one portrait of the American Dream.

(Heads up: The wall script tells me a Peckerwood is a loud and troublesome red-headed woodpecker found in Mr. Dial's neighborhood, and also derogatory slang for racist white folks.)

Walk around behind this façade past the low platform and the "Please Do Not Touch the Art" script, and a burnt, charred, wired up steel-strapped wall of rotted plywood supports the façade around front. A figure molded from bent steel, a twisted, burned stump and a painted blood red cloth stands behind the door. The backside of this house in Peckerwood City has a sad, ethereal, beat-down quality to it, a spirit of defiant, raggedy rectitude running through it, as do many of the pieces here.

My mother used to tell me, "Behind every great fortune there is a great crime." (She was a closet Socialist.) Thornton Dial is saying that behind every small fortune is a small crime. Dial is telling me it's very possible someone's blood, sweat and tears built this house for someone else to live in. It doesn't say that on the wall writing; that's just me and my mother taking a guess.

David Driscoll, along with some of the other fine writers who contributed to the book which accompanies this show, refers to the dignity Dial pursued and achieved in his long life and struggles. Dial's pursuit of recognition, respect and a deserved station in the canon of fine art has continued, even accelerated in his late life.

Dial grew up, worked hard and has long lived in a place and time which encouraged, sometimes demanded, he keep his head down and his eyes open. He worked in isolation and relative anonymity. He lived his hard life, and listened closely to missives sent his way from the outside world. He developed big and small worldviews, which he translated into a visual language, a private language, a language never seen before.

Grand, tough, hard, honest, bitter and sweet. With his clear eye, good mind, stubborn perseverance, and God-given virtuoso hands, he cobbled together the junk strewn about him and formed them into a vision every two-legged animal with decent eyesight can understand as true and powerful, brutal and sweet.

You can't go through life like that and not feel filled up, and filling up a few others along the way. Everyone who sees this show will leave the museum with an image of the man who made the work. Something to wrap your head around to imagine where this stuff came from.

I see Thornton Dial walking out of his home in Bessemer City, Ala., walking down to his cavernous, cobbled together barn studio, thinking about the little things and the big things weighing on his mind. Not because anyone told him the war in Iraq, or the price of corn meal, or the woeful treatment of neighbors and friends and family or poor folks or black folks was something he had to be thinking about. He's just thinking.

Past the pen with deer, the goats, the sleeping dog.

Past the piles of iron and copper and grayed and rotted wood, the tires, the bicycle wheels and the plastic spray paint caps piled in 55-gallon buckets.

He's grumbling half sentences parsed from full thoughts, feeling grumpy.

But he's feeling the spirit.

He wants to make things.

He's thinking mostly about one thing that keeps rolling around in his head. Can't keep it out, and won't let it go until he picks up one of the hundred thousand pieces of something orbiting his world like a friendly taunt; he rolls one thing around in his hand, and thinks of something to do with it.

And he starts to make something powerful and terrible and beautiful.

I get the feeling Mr. Dial is wary of white men, and so am I. Being white, however, I am wary for less blood-under-the-fingernails reasons, but I am wary nonetheless. What have we wrought with 500 years of big and small world domination?

The printing press, airplanes, Penicillin, the Red Cross, the geodesic dome, indoor plumbing, and a raft of other wonderful inventions making life better.

And we've brought poverty, subjugation, class and race division, environmental degradation, corruption and a raft of other problems making life worse.

We all see that spectrum, and we all stand on it somewhere.

Thornton Dial knows where he stands: "All truth is hard truth. We're in the darkness now, and we got to accept the hard truth to bring on the light. You can hide the truth, but you can't get rid of it. When truth come out in the light, we get the beauty of the world."

If you've budgeted your art-seeing time to one show this year, it's here at the Mint Museum Uptown through Sept. 30.

Speaking of...

Latest in Cover story

More by Scott Lucas

Calendar

-

An Evening With Phil Rosenthal Of "Somebody Feed Phil" @ Knight Theater

-

Kountry Wayne: The King Of Hearts Tour @ Ovens Auditorium

-

NEW WINDOW GALLERY-Pat Rhea-ACRYLIC PAINTINGS-April 05-30 2024 VALDESE, NC 28690 @ New Window Gallery/Play It Again Records

- Through April 30, 12 p.m.

-

Trap & Paint + Karaoke @ Zodiac Bar & Grill

-

LIVE MUSIC FRIDAYS!!! @ Elizabeth Parlour Room

-

Susan Brenner Examines Upheaval While Celebrating Trees

Chaos and beauty

-

Fall Guide: Upcoming festivals, comedy shows, visual arts events and more

-

Failure To Communicate

Worthy play could use more nuance