That's Critser's point. Obesity, he points out, is a condition that "disproportionately plagues the poor and the working poor," while public discussion and policymaking on the topic get steered by the middle and upper classes. A health journalist, Critser decided he needed to lose 40 pounds a few years ago. To do so he enlisted a competent doctor, the prescription weight-loss medication Meridia, jogs in a congenial neighborhood park, a wife who cooked him healthy food, and access to plenty of information.

"And money," he adds. "And time." He lost the weight, but "the more I contemplated my success, the more I came to see it not as a triumph of the will, but as a triumph of my economic and social class."

By contrast, he covered the opening of a Krispy Kreme doughnut store in Van Nuys, CA, a largely working-class Latino area, for Harper's magazine in 1999. The store manager explained to him, "We're looking for bigger families ... Yeah, bigger in size," meaning, I suppose, that Van Nuys residents have more kids, as many Latino families tend to do, but also that they're likely to be heavier than non-Hispanic whites. African-Americans are more likely to be overweight than either group. And the poorer you are, the more likely you are to be obese.

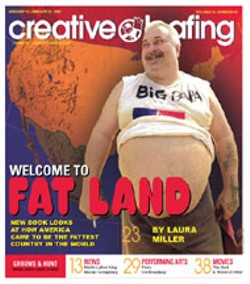

The association of fat with a lower social status is probably intuitive for most Americans, but so far that has mostly been treated as a cruel stereotype of the overweight, representatives of whom have gone on TV talk shows to tearfully protest that they are not "lazy" or "low class." The innovation Critser brings to the literature of obesity is to take what turns out to be a valid perception after all -- working-class and underclass people are more likely to be fat -- and pull a switcheroo. Rather than regard class status as a stigma unfairly affixed to fat people, he presents fat as a health liability unjustly foisted on the poor and insufficiently addressed by the affluent.

It's a refreshing argument and often quite persuasive. Critser also traces some developments in international trade, agriculture, social customs, marketing and food sciences that, he maintains, have conspired to boost the calorie content of the average American's diet. For instance, high-fructose corn syrup, a sweetener that fosters diabetes, and palm oil, said to enjoy many "molecular similarities to lard," have become pervasive in prepared foods since the 1970s, and they are two of the nastiest, most fattening concoctions known to man.

The portion of the average American's food dollar spent on meals obtained away from home jumped from 25 percent to 40 percent between 1970 and 1996. Restaurant food not only tends to be higher in calories (it adds 197 more per day, to be precise), it also comes in increasingly humongous portions, especially if you supersize your order. A regular serving of McDonald's French fries contained 200 calories in 1960; now it has 610. Then there are the between-meal snacks and the sedentary lifestyles.

As you might guess, Fat Land is packed with numbers, and while much of this is familiar stuff, some of the studies Critser digs up are fascinating. People, including children 5 and older, eat more food when presented with more of it, which pretty much dispenses with the notion that the body just naturally knows when it has had enough. On the contrary, natural selection has designed many of us to eat as much as we can get, as insurance against future deprivation. In fast-food restaurants, we eat more food when we get larger amounts of it at discount prices, and simply knowing that a greater variety of high-calorie snack foods has been made available to us apparently spurs us on to consume vast quantities of them. Critser debunks the idea that brief bouts of moderate exercise during the course of the day can make you as fit as sustained periods of vigorous activity, and that it's healthy to gain a few pounds as you get older.

Latest in Cover

Calendar

-

Wine & Paint @ Blackfinn Ameripub- Ballantyne

-

Queen Charlotte Fair @ Route 29 Pavilion

-

NEW WINDOW GALLERY-Pat Rhea-ACRYLIC PAINTINGS-April 05-30 2024 VALDESE, NC 28690 @ New Window Gallery/Play It Again Records

- Through April 30, 12 p.m.

-

TheDiscountCodes

-

Face to Face Foundation Gala @ The Revelry North End

-

Esports in Charlotte Takes Off: A Guide to Virtual Competitions and Betting

-

Homer's night on the town 41

If you drank a shot with the Knights mascot on Sept. 20, you were basically harboring a fugitive

-

Beauty Industry Trends To Look Out For In Charlotte In 2022