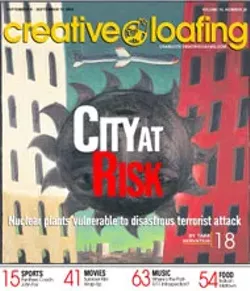

City At Risk

Area nuclear plants... vulnerable to disastrous terrorist attack

Now, a year after September 11, the more than a million people who live within 100 miles of McGuire or Catawba still have little idea of the death and devastation terrorists could wreak if they flew a large commercial aircraft into either of the plants' nuclear reactors, or into their highly radioactive, yet less protected, spent fuel pools.

But the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) knows. For 20 years, the federal agency that regulates the nation's 103 nuclear plants has been well aware that the infrastructure of the nation's nuke plants wasn't built to withstand the impact of a plane crash, no matter what nuclear plant owners told the public about the thickness of the walls around the reactor. The NRC had done studies that proved it. But no one spent much time worrying about those studies because the likelihood that a plane would happen to crash into a reactor seemed remote; the idea that terrorists on a suicide mission would aim one at a nuclear plant was unfathomable.

When the planes struck the Twin Towers, everything changed. Rather than move quickly to protect the country's nuclear plants, however, the NRC instead tried to hide the truth.

In the days after September 11, an obscure, 119-page report disappeared from the reading room at the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC). In it were the results of a study which showed that many of the large commercial aircraft flown today could easily crash through the protective containment buildings that house nuclear reactors, if they flew fast enough and carried enough fuel. In the aftermath of the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center, the NRC and other government officials initially denied that the country's nuclear reactors were vulnerable to aerial assault. But too many people knew about this report, as well as others that pointed to the same conclusion. Eventually, the NRC did an about face on the issue. But since the national media didn't do a particularly good job of covering the NRC's flip-flop, most people went about their lives, assuming their local nuclear plant, or in Charlotte's case, plants, were safe from terrorist attack.

The truth can be found in a press release you have to hunt for on the NRC's website. The statement says that nuclear plants "are among the most hardened structures in the country and are designed to withstand extreme events, such as hurricanes, tornadoes and earthquakes.

"However," the statement continues, "the NRC did not specifically contemplate attacks by aircrafts, such as Boeing 757s and 767s, and nuclear power plants were not designed to withstand such crashes." The NRC is currently studying the issue, and their analysis is due by the end of the year.

A 1987 report by the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory for the NRC was more explicit. "The effect of an aircraft of sufficient weight, traveling at sufficient speed, crashing at a nuclear power plant site may result in physical damage and disruption to the plant to the extent that damage to the reactor core and release of radioactive material from the reactor core may result."

Unlike the NRC, Duke Energy officials are frank about the relative strength with which the nuclear reactors at McGuire Nuclear Station were designed.

"We have definitively said they were not designed to withstand the impact of commercial aircraft," said Tim Pettit, manager of nuclear public affairs at Duke.

Although there's been a lack of in-depth coverage of power plant security in the Charlotte region, it's a very important issue. Up to 195,000 people stand to be in a 10-mile zone around McGuire Nuclear Station at any given time. The number jumps to more than a half-million in a 30-mile radius. In addition, some 156,000 people live in the 10-mile zone around Catawba Nuclear Station, just over the South Carolina border.

"It's an issue for every community that lives near a nuclear power plant," said David Lochbaum, a nuclear systems engineer and nuclear safety expert at the Union of Concerned Scientists in Washington, DC.

Incoming Mecklenburg County Homeland Security Director Wynn Mabry says Charlotteans should realize that there isn't another community in the country with two nuclear plants in such close proximity. "People in Charlotte should pay attention to your article," he said.

ForewarningMost Charlotteans probably haven't heard about the high-pitched battle currently being fought in upstate New York over the Indian Point Power Plant, but it directly concerns us, and anyone who lives in a high-population area around a nuclear plant.

On September 11, American Airlines Flight 11 roared over the twin domes of the Indian Point plant. Seven minutes later, the hijacked plane slammed into the north tower of the World Trade Center.

If the NRC's research over the past two decades is any guide, the planes that brought down the Twin Towers were big enough, and traveled fast enough, to have cracked open the concrete containment domes around the Indian Point nuclear reactors, potentially breaching the reactor and, according to at least one study, possibly causing a core meltdown. Because of its proximity to New York City, almost 17 million people, six percent of the US population, live within 50 miles of Indian Point nuclear plant. After September 11, the plant suddenly seemed an ideal target for terrorists. Nuclear watchdog groups in New York started asking questions they'd never thought to ask before. When the answers to their questions were printed in newspapers across the state of New York and neighboring parts of New Jersey, formerly apathetic citizens added their voices to a demand for the shutdown of Indian Point.

A survey conducted in November for an environmental group called Riverkeeper showed just how sorry a state the areas around nuclear plants might be in if they tried to implement their standard 10-mile-zone evacuation plans in the event of a nuclear emergency. The survey showed that a nuclear emergency would likely trigger mass evacuations well beyond the 10-mile radius that governments prepare for, causing bottlenecks and actually blocking in those closest to the plant. [See our accompanying story on local evacuation plans, "Traffic Jam From Hell"

Although some officials and scientists insisted that Indian Point and nuclear plants around the country are safe from attack, New Yorkers who now knew of the NRC's studies weren't buying it.

In February, New York Governor George Pataki asked the federal government to review emergency evacuation plans for all the country's nuclear power plants, including those for the areas surrounding Catawba and McGuire. In the meantime, 27 municipalities around Indian Point, as well as seven members of New York's congressional delegation, have demanded that the plant be shut down. The battle in New York still rages.

The Effect of A CrashBefore September 11, planning for nuclear disaster was probably pretty realistic, given the nuclear industry's decades-old, solid safety record. Not one American death has been directly attributed to a nuclear accident, including the well-known near meltdown in 1979 at the Three Mile Island nuclear power facility near Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.

But September 11 changed the way the federal government and the NRC looks at and measures nuclear security. In February, President Bush told the media that diagrams of American nuclear power plants had been found by US troops in abandoned enemy camps in Afghanistan. Since then, the relative vulnerability of these plants has been the subject of fierce debate among the nuclear energy industry, nuclear activists and nuclear scientists, all of whom use their own official sources, and none of whom agree.

At the heart of the debate are several studies.

A 1982 study conducted at Argonne National Laboratory in Illinois for the US Department of Energy and the NRC -- the study which was taken from the NRC reading room -- found that if a jet crashed into the concrete containment dome of a nuclear reactor at 466 miles per hour or greater, the explosion of fuel and fuel vapor from the plane could overwhelm shields inside the dome that protect the reactor. At 153 feet long and 336,000 pounds, the Boeing 707-320 used in the Argonne study was considered a large commercial jet at the time. By comparison, today's Boeing 767-300, the same aircraft that crashed into the World Trade Center towers, is 180 feet long, weighs 412,000 pounds and carries 23,980 gallons of jet fuel.

A 1987 study by the NRC at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory found that a 12,500-pound jet had a 32 percent chance of piercing the reactor containment building's six-foot thick base and an 84 percent chance of crashing through the buildings' dome, which was 2 feet thick. Again, the Boeing 767-300's that hit the Twin Towers weighed 412,000 pounds.

But even if a massive explosion didn't smash through the shields that protect the reactor, would the crash itself disrupt the plant's systems enough to cause a meltdown anyway, as the Argonne study suggests it might? Experts' opinions vary widely on what damage, if any, would be caused by the plane, burning fuel, or burning fuel vapor if it breached the reactor.

McGuire's 130-feet-wide, 160-feet-tall containment buildings have roofs of 1.5-inch steel that top shield building walls of three-feet-thick concrete. Inside it, a five-feet-thick reinforced concrete wall and a four-feet-thick leaded concrete bioshield with 1.5-inch-thick lining inside the reactor protect its core.

When Creative Loafing asked Duke Energy if its reactors could stand up to a terrorist attack by plane, we were given a copy of the same video widely distributed to the media in the Indian Point debate. The Sandia Laboratories video, which shows a jet slamming into a concrete wall, is initially compelling. In the video, an F-4 fighter jet crashes into the wall at 480 miles an hour. The plane is decimated, but the wall remains standing, virtually undamaged. After a little digging, CL learned what the video doesn't show: the wall the 42,000-pound F-4 jet crashed into was 12 feet thick and weighed 1 million pounds. And unlike most commercial planes flying today, the F-4 carried water instead of stored fuel.

When CL later questioned Duke Energy officials about the weight and thickness of the wall, it was explained to us that the purpose of the test shown in the video was to evaluate the behavior of concrete structures, not to prove that the containment structures on the site could hold up to aerial assault.

"People have asked that $64,000 question -- could the containment system survive a direct hit by a 757?" said Pettit, the Duke spokesman. "One of the answers to that is that's not really the issue. You want to know could the plant and all the redundant and diverse safety systems continue to cool the fuel and prevent a radiological accident from happening. Even if something breaches the reactor's containment structure, knocks the top off, crushes a big hole in the side, the reactor vessel is located in the heart of the building and is protected by multiple barriers of rebar-enforced concrete. Diverse safety systems are spatially located around the containment building to prevent taking out more than one component of the system."

Not exactly, said Lochbaum, the nuclear systems engineer with the Union of Concerned Scientists.

"The reactor vessel is a big pot," Lochbaum said. "Pipes carry water and steam in and out. If you broke either or both of the pipes [that carry steam or water in and out of the reactor] those backup safety systems would be useless."

Assuming that terrorists managed to crash a large enough plane through the walls of a reactor, he says, meltdown could be caused in one of two ways. The impact would disrupt the cooling flow of water through the reactor. The water would eventually boil; the reactor fuel itself would be uncovered, overheat, melt through some or all of its surroundings and release deadly radiation. Or, he says, the impact of a jet could cause the water to be drained out of the reactor right away, causing the meltdown to happen much quicker.

The nuclear industry recently commissioned and paid for its own study of reactor safety from the Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI). Preliminary results of the study indicate that a commercial aircraft like that used in the September 11 attacks isn't likely to penetrate the containment buildings that house the reactor or other buildings that store irradiated fuel.

Critics, however, say the results of this study are questionable at best, for several reasons. According to its website, EPRI, which has non-profit and for-profit arms, was created to represent and advocate for the interests of the energy industry, and to profit from providing consulting and research and development services to more than 1000 energy producing companies worldwide. Unlike the NRC studies, full details of how the study was conducted won't be released in detail to the public for "security reasons."

What EPRI was willing to divulge was that it tested the impact of a Boeing 767 upon a reactor using the ground speed and angles associated with the September 11 attack on the Pentagon. EPRI researchers contend that it would be virtually impossible for a pilot to maintain enough control of a commercial aircraft in a steep dive to hit the dome on the top of a containment structure, the weakest part of the reactor's protection system. The pilot would have to fly at low altitude where he could not maintain significant speed, EPRI contends, thus the plane they used in the test run only traveled at 300 miles an hour.

Less Protected So far, it's the nuclear reactors that have gotten the most public scrutiny when it comes to the possibility of terrorist attack. But what most people don't realize is that terrorists wouldn't have to hit the reactor to wreak deadly havoc.

Those who know the layout of nuclear plants say that the vast quantities of spent fuel stored at most US power plants, including McGuire and Catawba, could pose an even greater threat if attacked than would a reactor.

"Many of the spent fuel pools have six times as much fuel as the reactor," said Lochbaum. "It will have to cool for 10,000 years. It is a hazard in the reactor, and it is a hazard elsewhere."

An October 2000 NRC study of spent fuel pool accident risk found that half the commercial airplanes flying today could likely penetrate the reinforced concrete walls around the spent fuel pools and compromise the support and containment systems, causing coolant to drain out and the irradiated fuel to be uncovered. The uncovered fuel could catch fire with disastrous results, even years after its removal from the reactor core, the report said.

Where does the spent fuel come from and what is it? In a nuclear reactor, enriched uranium fills metal fuel rods that are grouped into fuel assemblies. After the fission of uranium generates heat and the fuel is spent, the radioactive assembly, the heart of the reactor, must be stored and cooled in water. McGuire has 2,152 of these assemblies stored in its fuel pools. Catawba has 1,780. These assemblies contain one of the nation's most lethal sources of radiation, second only to that found in the core of nuclear reactors, where the spent fuel originates.

Unlike the nuclear reactor containment buildings, which have seven reinforced layers of protection between the core and the outside world, the lethal radiation in spent fuel pools at Catawba and McGuire is protected by only two feet of reinforced concrete and another two feet within the pool itself, which is located just below ground level.

"The NRC has never tested the security of spent fuel storage," Lochbaum said. "Since 1991, the NRC has been focusing security testing on the security of the reactor. They have exercises with a small band of intruders and see how well the security holds up. Every one of them had the reactor as the target. Not one of them tested the spent fuel. While there are gates and alarms, no one has ever tested them. We can't see that there aren't seams or gaps someone might want to exploit. We think security needs to be beefed up."

It's not just the strength of the reactor or the spent fuel pools that most worries Lochbaum. He believes that terrorists might also attempt to attack the plant's control room. Debate over whether McGuire and Catawba's control rooms would be functional after an attack is inconclusive. Nuclear scientists like Lochbaum and Lyman say the plants' control rooms are vulnerable because they are located outside the reactor and because the plants' control rooms weren't designed to withstand the impact of large explosions of a jet. Duke Energy's Pettit points out that if the control room is hit, a backup safe shutdown facility exists, in addition to a third set of electrical panels with switches like breakers that could be used to manually shut down the reactor in the event of an emergency. Pettit said that even if the control room operators were killed in an attack, the plant could call in other operators who work different shifts or make use of control room operators who work outside the control room. But again, Lochbaum argues, that assumes a slow enough leak of dangerous materials that new operators could be brought in before it became serious.

"If they are responding to a terrorist attack, they may only have a few minutes, or, depending on the damage involved, the operators may not be able to get to the control panels," he said.

In Everyone's BackyardThe nuclear safety debate is both local and national at the same time. That's because nuclear radiation doesn't recognize the 10-mile zone around the plant where most evacuation plans stop, says Paul Gunter, director of the Reactor Watchdog Project for Nuclear Information and Resource Service in Washington, DC.

"If there is a catastrophic release, it will be borne on the wind for hundreds, if not thousands of miles," said Gunter. "If it is raining, you'll get very high concentrations closer in to the plant about 50 to 100 miles. There are still farms in Cumbria, England, that have restrictions on human consumption of lamb because the spring grasses are bringing up Cesium 137 from the Chernobyl power plant meltdown in the Ukraine."

Counter-terrorism expert Tom Bevan, Director of Homeland Defense at Georgia Tech, spent years studying the fallout from the Chernobyl accident. He says that although the technology used at the nuclear plant at Chernobyl is different than that used in the US today, the potential results of a radioactive fire on the area surrounding a nuclear plant remain the same.

"If a reactor catches fire from a load of airplane fuel, then things will go in the atmosphere and spread around," said Bevan. "It's not a clean nuclear reaction [such as those] the military studies when they plan how they would respond to these things."

Bevan said that based on what happened at Chernobyl, there would be a main zone about 18 miles around the plant where no one could live. Most of the radiation would be concentrated in a zone that stretched 40 or 50 miles out from the plant but, like Chernobyl, a certain percentage of the fallout would spread across the country.

"There's still a big pocket of it in Belarus, 400 miles from Chernobyl," he said.

But the fallout would do more than physical damage. It would make the surrounding community virtually unlivable, the economic implications of which would be locally, and even nationally, staggering.

A 1982 analysis by Sandia National Laboratory for the government showed the physical and economic damage that could be caused by a total meltdown at any of the country's nuclear power plants. This is relevant to Charlotte since, as the 1987 Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory report found, a plane smashing into a nuclear station could result in a similar release of radiation. The bottom line of the Sandia Lab report: People who lived within 35 miles of the plant would have to leave their homes and their businesses; they likely would never be able to return.

That's because as the radiation plume traveled, it would disperse radioactive particles that could be inhaled, swallowed, or absorbed through the skin. They could dissolve in water, coat homes and vehicles or travel on the fur of pets. Like at Chernobyl, radioactivity would poison land and the food grown on it a minimum of 40 miles away, and likely much farther. Water supplies would be unusable for decades and reservoirs might have to be condemned. Home and business owners would likely face costly cleanups if the structures they owned were still habitable, which would be unlikely. In heavily populated areas around nuclear plants like Indian Point, or McGuire and Catawba, that could be financially devastating for the region, and ultimately the entire country.

Special thanks to the New York Daily News reporters whose collaboration with Creative Loafing helped make the research for this story possible.

Speaking of News_.html, 5.00000

-

A Family Affair

Dec 12, 2007 -

Darrell Roach

Dec 12, 2007 -

Body Talk

Dec 12, 2007 - More »

Latest in Cover

Calendar

-

Queen City Mimosa Festival & Day Party @ Blush CLT

-

Queen City Tequila Festival @ Blush CLT

-

Coveted Luxury Watches

-

TheDiscountCodes

-

Celebrate AAPI Food, Culture, & More at Panda Fest Charlotte! @ Ballantyne’s Backyard