The Price of Care

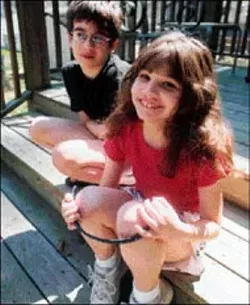

NC families fight to keep developmentally disabled loved ones where they belong -- at home

By Reuben BrodyWith the rise of developmental disabilities in the mid-80s, it was deemed that institutionalization was too expensive to serve every person, because the services offered by the institutions exceeded the needs of most patients. The federal government developed a remedy: Medicaid waiver programs, in which the federal government would match state and local governments on a sliding scale. (The feds currently match North Carolina by a ratio of roughly 70-to-30.)

According to Lisa Haire, acting director for Regional Support Services, "Each state has to be able to match what the federal government hands down based on a formula that the federal government hands them." Every state has a waiver program. North Carolina named its program Community Alternative Program, or CAP.

Programs like CAP, combined with the recent Olmstead Supreme Court decision -- which stated that institutionalization was inhuman and discriminatory toward people with developmental disabilities under the Americans with Disabilities Act -- have pushed movement toward community-based care programs and group homes nationwide. The fact that North Carolina has not complied with the Supreme Court's ruling has made many NC residents, as well as outside observers, concerned.

Unfortunately, North Carolina still relies on institutional care, allotting the majority of its Medicaid money to those antiquated facilities.

"More of our money goes to these institutions," explains Linda Guzman, a chapter and advocacy specialist with the Arc of North Carolina (an advocacy organization established to aid families and those with developmental disabilities). "There are people who want to leave institutions but who can't because these services aren't available in the communities."

Guzman agrees that North Carolina is downsizing its institutions. However, only now is the state beginning to take the matter seriously. As one institutional administrator divulged, "The interesting thing about mental health reform is, and this is just my perspective on it, some of the issues that are being looked at are being forced to be looked at because of the budget situation, but they needed to be looked at anyway. And I kind of believe that if it had not been for the budget crisis, they wouldn't have been looked at. Not only the money, but whether or not there are the best services and to the most needy people and all of that."

According to Nina Yaeger, an employee at the Division of Medical Assistance, North Carolina's "state general fund is forecast to be short by $950 million this year." This is a big motivator for the government to make some changes in how they spend their money.

CAP is a program that offers these services within the community. Polly Medlicott receives help for Christian from a private care nurse, Barry Parker. Parker assists Polly with Christian in the mornings by helping him with his education and physical therapy. Polly found Parker on her own, but normally she would have gone through a private care agency to acquire the type of care a nurse like Parker provides. These provider agencies submit the bill to the Division of Medical Services, and they act as the state's Medicaid agency.

This is one of CAP's glitches. Under the current CAP situation, families are assigned case managers, and those case managers oversee the money each family is allotted. Case managers receive a $500 payment per family each month to assist that family in acquiring services needed by the individual, such as finding a care provider or a physical therapist. The problem with this system is that case managers are private businesses. Since these institutions have to receive payments from the government for their services, they can only pay their employees so much and still turn a profit. The result is that employees hired through those agencies don't remain with any one company for too long, because the pay and the benefits are sub-par. This creates a problem, because caseworkers don't develop a relationship with the families they're serving, which makes it difficult to understand the families' needs. In addition, developmentally disabled people typically take longer to establish the trust of an outsider, and if outsiders are constantly popping in, it becomes distressing for the person who truly needs the care.

"A lot of the problem we have in CAP is that the case managers are transitory, which is a huge turnover," says Polly Medlicott. "You get a case manager, and you sort of have [to] train them. You kind of go through this process and they're gone. Families find it difficult to hold on to their care provider because they have no incentive to stay."

Another problem with the agencies is that they take a percentage of the money earned by the care provider. Some families feel there should be a choice of whether private agencies should be used, because then there would be no middleman to gobble up the excess money, which in turn would pay the care provider more and ensure better care.

It becomes more of a problem for families with two children in need of services. Take the Scandariatos -- they've got two children served under CAP. The family is served under an SLP-20, which decreases the individual hourly rate from $22 an hour per person to $28 an hour collectively. The money is taken from each child's budget, and the savings go to Medicaid.

"If you use over a certain number of Individual Periodic hours in the course of day, and I think that the number is like three and three quarter hours, if you use any more than that you have to have an hour of MR Personal Care in there." Explains Karen Scandariato. "MR Personal Care pays like $7.50 an hour. With Group SLP, it pays like $16 an hour, in my case out of the two children out of that $28. Now I'm expecting that same person, who's already in my home to work $16 an hour some hours and others at $7.50 an hour. Would you do that? No."

Coming Up With Their Own Answers

Several families (including the Medlicotts and the Scandariatos) who are served under the CAP Mentally Retarded/ Developmentally Disabled waiver have discovered a way to save the state $82,790 on 12 families this year alone. Under a pilot program called CAP SMART, the families have adopted a hypothetical "self-determination project" to find more efficient techniques of getting quality care at the lowest possible cost. The idea was to save the state money by using the funds allotted to their children through Medicaid to finance their health care. These 12 families have been attending seminars with the state partners as well as the Arc to determine the best way to administer community-assistance programs. They've also been sharing their experiences with the state government so that considerations can be made under the new system.

Polly Medlicott and the other 11 families under the "self-determination project" would like to see this accomplished.

"I don't need a case manager," attests Polly. "I'm my own case manager. In self-determination, the way that it works is they are support brokers, which is somebody that you like, that you want and understands what you want for your family member, and they go out and try and find the services in the program and help you with ideas and whatever." As she said, she is her own case manager so she doesn't even need this service, but some people do.

"With self-determination, the money follows the person," explains Polly. "Say if that person left the institution and went into the community, it's not going to cost the state extra."

"Right now we don't have the mechanism to allow that type of spending," commented Peggy Balak, the Program Support Branch Head of Developmental Disabilities for the state of North Carolina. "We are trying in modifications to make the system more flexible. However, our ability to give a family direct cash payment or even a voucher is limited by the restrictions in the Medicaid waiver. But you cannot give cash payments to a minor child. The waiver won't allow us to do that for anyone at this point."

Barry Parker is a trained professional, so the care he gives Christian Medlicott is equal to what Christian would receive in an institution. One of the main differences in this type of care is that Parker only provides the type of care Christian needs, whereas, if Christian were in an institution, he would receive blanketed care for needs that he might not need met.

According to one institution administrator, institutions provide total coverage care, regardless of whether a patient needs that care. This is incredibly expensive and wasteful, yet that is how institutions operate.

With that said, families with members in those institutions have no say as to how their loved ones are cared for. For the Medlicotts, that was enough to withdraw Christian from public school.

Ever since Christian was born, the family has believed in a homeopathic philosophy of prevention through diet over medication. Polly prepares organic meals for Christian using all the oils and proteins necessary for a healthy lifestyle -- minus all the fat, of course. Christian has an excellent bill of health, but at one point that was in jeopardy because the public schools misunderstood him.

When Christian hit puberty, his endocrine system went "crazy," and so did his hormones, which resulted in a mysterious inability to swallow food. This happened while Christian was in school and, according to the teachers, Christian turned blue, so of course they called 911. By the time Polly arrived at the hospital, Christian was fine. Polly said this occurred several times at home and she never had to take Christian to the hospital. One of the teachers at Christian's school wanted to have a feeding tube inserted into Christian's throat. Polly was appalled by the notion; she didn't want her son to be fed the cornstarch-based sludge that slithers down surgical feeding tubes.

"I didn't want him to have surgery, and I didn't want him to have a feeding tube eating that awful crap. That formula that's full of corn syrup, that is supposedly nutritious. And he loves to eat. It's his favorite thing. If you took away eating, he would get depressed. I think that that happens to a lot of people."

Misunderstandings are common in the developmental-disability world. These shortcomings are no doubt the result of a lack of patience and ignorance on the part of the rest of the system. Not all developmentally disabled people are mentally retarded, which is a common misconception. People assume that because a person can't speak, he or she has the overall intelligence of a 3-year-old. But that's not true. Developmentally disabled people don't communicate in the same ways we do. There are not many programs offered through the state that work on communication skills for the developmentally disabled outside group homes or institutions. It costs families around $45 a session to administer treatment that incorporates the visual, musical and dramatic arts as an outlet for expression; despite studies that have proven that art therapy has merit, these programs aren't offered through CAP.

According to Balak, the Program Support Branch Head of Developmental Disabilities, "Under Title 19 of the Social Securities Act, which is a federal law, are the Medicaid laws that establish Medicaid money. In the field of developmental disabilities, the money funds intermediate care facilities for people with developmental disabilities and retardations level of care. When they fund level of care, they fund facilities, ICFMR group homes and ICFMR-certified beds around the country."

Basically, under the current system, institutions are first priority for the money. This means no new families can apply for the waiver program this year. Those families left out will have to seek institutionalization because the waiver program is frozen. However, if you needed care under Medicaid, you could be serviced through an institution. This is a big problem for North Carolina, since that is in direct violation of the Olmstead decision.

Institutions actually cost more per person than the waiver programs. Advocates of dismantling institutional living say institutions are inefficient anyway, and we should move to more community-based programs like CAP and group homes.

Technical difficulties arise, though, because some people need constant care. For instance, there was one patient at an institution who would gouge his body. The institution has to strap him down so he won't rip gaping holes in his body. Instances such as that, albeit rare, are what some folks contend are reasons to keep the institutions open. Others, like Denise Mercado (a mother in one of the 12 families), feel the person would be better served in the community through a group home -- not only because it's more cost-effective, but because that person could receive the proper care, which could lead to the root of the patient's problem and not merely treat the symptoms.

"We never ask why?" comments Mercado. "We just treat the symptoms, and rarely address the underlying issue. Let's give them a reason to stop doing that kind of behavior."

The governor's office considers mental-health reform an important issue needing change in North Carolina. It has recently appointed Dr. Richard Visingardi as head of the state's Division of Mental Health, Developmental Disabilities and Substance Abuse. Visingardi has extensive experience as the head of a community agency in Michigan, where he supervised a $200 million program.

But the reality is that change doesn't occur at the bat of an eye, especially in the South during a sludgy economy. Infrastructural changes need to be made in order for the people in the institutions to have care when they leave those institutions. Not only that, but the communities need to be ready to support those individuals after they've left. The current budget crisis is a real roadblock because the money that needs to be used to build the infrastructure does not exist as of yet.

An article in the Raleigh News & Observer credited Visingardi with having shifted "240 staff members who worked for the county agency to a private nonprofit company." This reduced his staff to 80 employees from the 400 with which he began. The question on a lot of people's minds is: Can we afford the loss of jobs in rural areas where there are no jobs due to the death of textiles and tobacco? Furthermore, citizens can't afford the taxes needed to kick-start the programs, so where will the money come from? It will have to come from job cuts and restructuring. However, it is assumed that some jobs will be created and absorbed through specialization in the private sector.

Recent studies show a rise in developmental disabilities throughout North Carolina. This increase, combined with the fact that every person with a developmental disability will have to go to a provider agency when institutions are dismantled, exemplifies how new jobs could be created.

"The problem," says Lee Cuvington of Tri-Alliance, an umbrella organization of the Arc, "is that there is not enough equal access across the state." The hope is that under the new program, jobs will be created based on that fact.

"Things are always changing," says Polly Medlicott of Christian. "That's what you have to deal with. And I had to deal with my own feelings. Having a better attitude helps." *

Speaking of Metrobeat.html, 2.00000

-

Letters To The Editor

Nov 28, 2007 -

Zoom-Zoom

Nov 14, 2007 -

October's Fests

Oct 3, 2007 - More »

Latest in News

More by Reuben Brody

-

Mad Vibrations

Mar 5, 2003 -

Play Dirty

May 8, 2002 - More »