The Price of Care

NC families fight to keep developmentally disabled loved ones where they belong -- at home

By Reuben BrodyPage 3 of 4

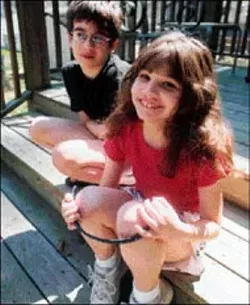

Barry Parker is a trained professional, so the care he gives Christian Medlicott is equal to what Christian would receive in an institution. One of the main differences in this type of care is that Parker only provides the type of care Christian needs, whereas, if Christian were in an institution, he would receive blanketed care for needs that he might not need met.

According to one institution administrator, institutions provide total coverage care, regardless of whether a patient needs that care. This is incredibly expensive and wasteful, yet that is how institutions operate.

With that said, families with members in those institutions have no say as to how their loved ones are cared for. For the Medlicotts, that was enough to withdraw Christian from public school.

Ever since Christian was born, the family has believed in a homeopathic philosophy of prevention through diet over medication. Polly prepares organic meals for Christian using all the oils and proteins necessary for a healthy lifestyle -- minus all the fat, of course. Christian has an excellent bill of health, but at one point that was in jeopardy because the public schools misunderstood him.

When Christian hit puberty, his endocrine system went "crazy," and so did his hormones, which resulted in a mysterious inability to swallow food. This happened while Christian was in school and, according to the teachers, Christian turned blue, so of course they called 911. By the time Polly arrived at the hospital, Christian was fine. Polly said this occurred several times at home and she never had to take Christian to the hospital. One of the teachers at Christian's school wanted to have a feeding tube inserted into Christian's throat. Polly was appalled by the notion; she didn't want her son to be fed the cornstarch-based sludge that slithers down surgical feeding tubes.

"I didn't want him to have surgery, and I didn't want him to have a feeding tube eating that awful crap. That formula that's full of corn syrup, that is supposedly nutritious. And he loves to eat. It's his favorite thing. If you took away eating, he would get depressed. I think that that happens to a lot of people."

Misunderstandings are common in the developmental-disability world. These shortcomings are no doubt the result of a lack of patience and ignorance on the part of the rest of the system. Not all developmentally disabled people are mentally retarded, which is a common misconception. People assume that because a person can't speak, he or she has the overall intelligence of a 3-year-old. But that's not true. Developmentally disabled people don't communicate in the same ways we do. There are not many programs offered through the state that work on communication skills for the developmentally disabled outside group homes or institutions. It costs families around $45 a session to administer treatment that incorporates the visual, musical and dramatic arts as an outlet for expression; despite studies that have proven that art therapy has merit, these programs aren't offered through CAP.

According to Balak, the Program Support Branch Head of Developmental Disabilities, "Under Title 19 of the Social Securities Act, which is a federal law, are the Medicaid laws that establish Medicaid money. In the field of developmental disabilities, the money funds intermediate care facilities for people with developmental disabilities and retardations level of care. When they fund level of care, they fund facilities, ICFMR group homes and ICFMR-certified beds around the country."

Basically, under the current system, institutions are first priority for the money. This means no new families can apply for the waiver program this year. Those families left out will have to seek institutionalization because the waiver program is frozen. However, if you needed care under Medicaid, you could be serviced through an institution. This is a big problem for North Carolina, since that is in direct violation of the Olmstead decision.

Institutions actually cost more per person than the waiver programs. Advocates of dismantling institutional living say institutions are inefficient anyway, and we should move to more community-based programs like CAP and group homes.

Technical difficulties arise, though, because some people need constant care. For instance, there was one patient at an institution who would gouge his body. The institution has to strap him down so he won't rip gaping holes in his body. Instances such as that, albeit rare, are what some folks contend are reasons to keep the institutions open. Others, like Denise Mercado (a mother in one of the 12 families), feel the person would be better served in the community through a group home -- not only because it's more cost-effective, but because that person could receive the proper care, which could lead to the root of the patient's problem and not merely treat the symptoms.

Speaking of Metrobeat.html, 2.00000

-

Letters To The Editor

Nov 28, 2007 -

Zoom-Zoom

Nov 14, 2007 -

October's Fests

Oct 3, 2007 - More »

Latest in News

More by Reuben Brody

-

Mad Vibrations

Mar 5, 2003 -

Play Dirty

May 8, 2002 - More »