Teachers Are Demanding More Than Just Better Pay

The state of education

By Courtney Mihocik @CourtneyMihoOn May 16, a sea of red descended on Raleigh.

Thousands of teachers across the state of North Carolina put in requests for leave and swarmed the streets, meeting with legislators to demand better pay, more funding and proper respect toward their profession. They donned red shirts that showed their alliance with the #RedforEd movement that has been sweeping North Carolina and the country.

Many educators in the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools system joined their colleagues for the march — enough of them that the school district and many others across the state had to shut down for the day.

If the state's educators are moved enough to march on Raleigh in droves, then there is a problem in the public education system.

Despite that day of action, many teachers still feel as though they have not been heard as they come into a new school year.

Kristine Barberio was an administrator in CMS for four years before she returned to the classroom for three years in Union County Public Schools. She has since transferred to Socrates Academy, a charter school in Charlotte.

"I think in general my concern about North Carolina is that teachers simply don't have a voice," she said.

Barberio described situations in which she felt teachers and educators were disrespected in the workplace but there was no well-structured formal complaint system to turn to. These complaints could vary from being asked to attend meetings during lesson planning periods or to perform tasks far outside of their job description.

Intense and interruptive testing schedules made it difficult for Barberio to effectively teach her students, she said.

Additionally, an increase in classroom sizes and a lack of funding for supplies and materials has also led educators to feel disrespected in their schools.

Part of what drew Barberio out of the public school system and into a charter school was the amount of freedom she felt she had to teach and advocate for herself and her students' educations.

"I felt like I could actually teach my students again," she recalled. "So instead of being asked to write lengthy mission statements on the board every day, having so many initiatives and programs that I was constantly trying to meet. [At Socrates Academy] I felt like I could go back and do my job and really advocate for my students."

Another prominent problem that educators and school systems across the state are experiencing is reduced education budgets and monetary investment in schools.

Mark Jewell, president of the North Carolina Association of Educators, said that he came to North Carolina 21 years ago from West Virginia, citing that his home state was not valuing and investing in education as much as he would have liked.

Jewell stated that the appeal of North Carolina in the late 1990s was its long-term strategic plan to invest in education. Investments in professional development and teacher salaries drew him to the state. Unfortunately, those things that appealed to him have since disappeared.

"All of these things that brought me here were wiped out by the General Assembly in 2013 basically," he said starkly. "I want to return North Carolina back to that leader of the southeast where it was a teacher destination for educators from across the country."

He also said he sees a lack of funding as an indicator of what the state values.

"You put your money in what you value," he stated. "And the state of North Carolina has not been valuing public education."

At the ground level, Melissa Einsley, a science teacher at McClintock Middle School sees this lack of funding affecting her and her students in the classroom.

"You always have to buy your own supplies a lot of the time," she said, a sentiment that many teachers echo. She added that she spends about $250 to $500 a year on supplies. "Pencils, paper, notebooks, glue sticks ... I always buy headphones, eraser tips, lead. You know these are basic supplies that some of my kids don't even come to school with. I've bought backpacks before!"

Einsley finds a link between school children lacking in supplies and the behavioral issues that occur.

"Kids don't want to be left out, they don't want to be that student that doesn't have the supplies for whatever reason," she stated. "A lot of behavioral problems are based on students that just can't do things."

Once her students have the right supplies and can keep up on work, Einsley said "their whole outlook changes," and while they might have once been a discipline issue in the classroom, "now they're actually trying."

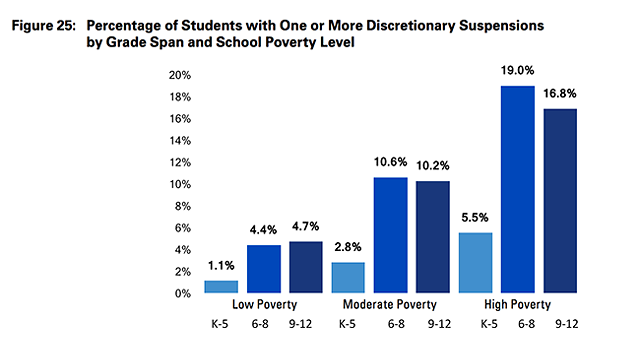

In February, the school board released a carefully compiled report called Breaking the Link. In it, the school system measured the positive correlation between the level of poverty of the schools in the district and the discipline issues that occur. Schools categorized as "high poverty" schools, like McLintock, tend to have higher instances of disciplinary action.

At-large CMS School Board member Elyse Dashew helped in compiling the Breaking the Link report. She said hopes the report will help shed light on the problems occuring so that the community can respond appropriately.

"I think there is a growing realization in Mecklenburg County that not everyone has the same access to opportunity," Dashew said. "There's a big disparity there and those problems in our community show up in our schools. And we can address a lot of those problems in our schools if the whole community can work together on it."

These problems also manifest physically in the school buildings.

Recently, a report surfaced that CMS had tested the water in 58 schools last fall and 27 of them were found to have dangerously high levels of lead contaminants. Of those 27 schools in the district, 13 were categorized as "high poverty" in the Breaking the Link Report.

Renovations are clearly needed in buildings across the district, but the county is having trouble getting the funding.

"We have schools that are so incredibly overcrowded and so many schools that are over 50 years old that are crumbling because we haven't had the funding for catching up with that," Dashew lamented. "That is not healthy for our kids or our teachers. That is not a healthy environment to spend however many hours a day, and however many days a year that our kids and teachers are together."

Many who are not familiar with the way that North Carolina's government is set up may be quick to point the finger at the school district or the county for not providing the funding necessary to give teachers a better salary, the budget for basic school supplies or to renovate and maintain the physical condition of the schools.

But the problem stems from the immense power of the General Assembly and an old 1868 Supreme Court ruling from Judge John Forrest Dillon, who opined that local municipalities derive their power from the state. Under this legislative philosophy, cities and counties cannot make their own ordinances or laws unless sanctioned by the state government.

Charlotte saw Dillon's rule in action during HB2, in that the state legislature contravened the city's ability to create anti-discrimination ordinances.

School districts and counties create budgets that they propose to the state. The amount of it that is allocated is ultimately up to the General Assembly.

N.C. Rep. Mary Belk, the Democratic representative for district 88, said that when the General Assembly issues statewide education mandates and doesn't fund them, it creates a hardship on the counties.

"By not funding the teachers the way they should and not having the number of the teachers and support personnel, that puts the burden on Charlotte-Mecklenburg," she said.

These may not be huge issues now, but Rep. Belk thinks it could be a bigger issue down the road when teachers begin to leave the school districts for better opportunities.

"As matter of fact, not funding adequately — and not having enough teachers and not having those teachers respected enough to give them their professional demands as far as compensation and as far as help — hurts industries because we're going to end up losing teachers and continue to lose teachers."

Ultimately, the health of the public education system affects the health of North Carolina's economy. When schools are rated poorly, industries and families will leave districts, counties and the state in search of better public education for children.

"Public education is the economy. It's going to affect property values. It's going to affect industries coming into North Carolina," Jewell stated. "Nobody wants to bring their company down here. You got to put all your employees and their kids through private school because the [public] schools are under-resourced."

While teachers like Barberio and Einsley are aware that some may look on their decision to march on Raleigh in May as a march for more money, they have made it clear that it's about much, much more.

It's about caring for the children that enter their classroom every day, and having the respect that a trained professional in any other industry would have. It's also about coming together in strength and having the support of their community.

The march was a way for teachers to let the community know what they were experiencing. It was a call-to-action for all of North Carolina and to the General Assembly. But they know that mending the public school system will take a long time; large changes will not happen right away.

"I think if we are going to be successful in North Carolina, we have to think incredibly long-term and incredibly strategically because this will not be fixed overnight, because it's been torn apart for years," Barberio said.

But, with the support of their communities, teachers in CMS and across the state can start to feel the ripple effects of their march, especially when gratitude and appreciativeness is voiced by people like parents, neighbors and administrators.

"There is this sense that teachers aren't valued and aren't respected in the general community," Dashew commented.

"I, as one school board member, try to make it my mission to shift that narrative and to remind people that I interact with in everyday life to how grateful we need to be for our teachers, and how we need to respect them for the professionals and experts that they are."

Speaking of...

Latest in News Feature

More by Courtney Mihocik

Calendar

-

Cirque du Soleil: OVO @ Bojangles' Coliseum

Cirque du Soleil: OVO @ Bojangles' Coliseum -

Coveted Luxury Watches

-

TheDiscountCodes

-

Queen City R&B Festival & Day Party @ Blush CLT

-

R&B Music Bingo + Comedy Show @ Blush CLT