Monday, August 4, 2014

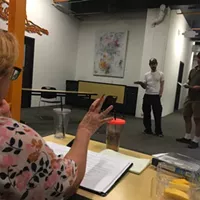

Arts Theater review: Dream a Little Dream

Posted By Perry Tannenbaum on Mon, Aug 4, 2014 at 1:14 PM

Notwithstanding the eternal veneration widely lavished upon Cass Elliot, who achieved martyrdom via precipitous weight loss or a ham sandwich, and despite the appeal of “California Dreamin’,” I’ve always regarded the vibrato-less Cass and the quirkily-clad Mamas and the Papas as incurably wholesome and vanilla. So I was taken pleasantly by surprise when I found Dream a Little Dream so enjoyable in its Charlotte premiere at Actor’s Theatre of Charlotte.

The script, by surviving Papa Denny Doherty, takes us behind the scenes, chronicling the origins of the core quartet, its rise to fame, and the complex of relationships that broke them apart. So it belongs firmly in the new generation of jukebox musicals that have departed from the patchwork tradition of Mamma Mia and All Shook Up, which followed in the footsteps of Crazy for You and its kind, where fictional characters and storylines strung the songlists together.

Co-written with Paul Ledoux, Little Dream is intimate, trashy, and autobiographical, so we get vivid tell-all accounts of our celebs, very much like we find in Jersey Boys or the more recent Carole King. Even if you’ve never grooved to the music or worshipped at the altar of Mama Cass, you’re likely to find this elegant production, directed and choreographed by Tod A. Kubo, to be both a nostalgic and a guilty pleasure — or a useful exposé on how messed up your parents were when they were your age.

For starters, it’s beautifully sung and played. Scenic design by Chip Decker isn’t really that distinctive — the studio portion could be warehoused until Actor’s Theatre stages The 1940s Radio Hour — but video and sound design by assistant director Kelly Truax stamps the biomusical with authenticity. Costumes by Magda Guichard and lighting design by Hallie Gray also compensate for the generic set.

Two factions needed to bridge their differences for the group to crystalize. The more dramatically compelling of these is John and Michelle Phillips. John is brilliant and talented, the group member who wrote the songs, but his artistic judgments are channeled through his loins. Whatever group he forms, the beautiful Michelle must be part of it, though her singing isn’t particularly distinguished, even when she does find the right key.

- Photo courtesy of George Hendricks Photography.

So it’s this perverse blindness that keeps Cass, obviously a superior performer, out of John’s inner circle until their mutual friend Doherty can convince the willful leader that Cass is the missing link who will make the group gel into something special. After wielding the guitar in the Beatles-flavored Love’s Labour’s Lost earlier this summer on the Uptown Green, it’s only a short leap for Grant Watkins to give us a Phillips who makes us grit our teeth with his stubbornness and smile with his hippy-dippy musical spirit.

Caroline Bower toughens her customary ingénue persona so that Michelle emerges as a somewhat milder replica of John, neither slutty nor arrogant, just naturally free-spirited and promiscuous — without the talent that would make us easily forgive her. Michelle does acknowledge in Act 2 that Cass has taught her how to sing, evolving from a simple drama queen and allowing Bower to unveil her formidable gifts.

You’ll have no trouble believing that Cass can do that righteous teaching with Brianna Smith wielding her vocals. While I didn’t always hear Mama Cass’s full range, Smith is more compelling within her comfort zone than any recording I’ve heard by Cass — though studio recordings are notoriously antiseptic. There are enough times when Smith’s sound converges with the Cass Elliot hits to make her performance uniquely satisfying.

Not surprisingly, Doherty is the most layered character we see, for he is not only the catalyst in the formation of the Mamas and the Papas, his chemistry with Michelle is at the heart of the group’s eventual breakup — rousing the jealousies of both John and Cass. After too long an absence from the Charlotte scene, Jon Parker Douglas reminds us, with seeming nonchalance, how artful and versatile he can be onstage as Doherty, taking a large share of the lead vocals, often bombed or stoned.

While “Dedicated to the One I Love” kicked things off at a painfully sluggish tempo, it wasn’t long before the singing and instrumental quartets began to click under the musical direction of Mike Wilkins. “Do You Believe in Magic,” “Go Where You Want to Go,” “Dancing in the Street,” and “Monday, Monday” all had a festive energy. Plopped into the richer context of Doherty’s book, “Creeque Alley” was less cryptic and more intelligible than ever; and Joseph Klosek, as sometime Papa Scott McKenzie, delivers soulfully in “San Francisco (Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair),” his one chance to shine musically.

Klosek resurfaces in multiple roles, including John Lennon, but it’s Matt Cosper who does most of the scene stealing in multiple comical vignettes, including record producer and rock hall-of-famer Lou Adler. As fun-loving as I’ve ever seen him onstage, Cosper is the only performer proscribed from singing. Chaz Pofahl and Nicia Carla also go through multiple costume changes that help to tell the story, but they also excel when the vocal arrangements need a little extra lushness.

By the time Smith sang the title song, she and her ace cast mates had softened me up sufficiently so I could swallow the ending despite its saccharine aura. Mama Cass idolaters, on the other hand, will be over the moon.