Thursday, January 19, 2012

Film / Film Reviews Phil Ochs: There But for Fortune sings tale of political disillusionment

Posted By Mark Kemp on Thu, Jan 19, 2012 at 10:00 AM

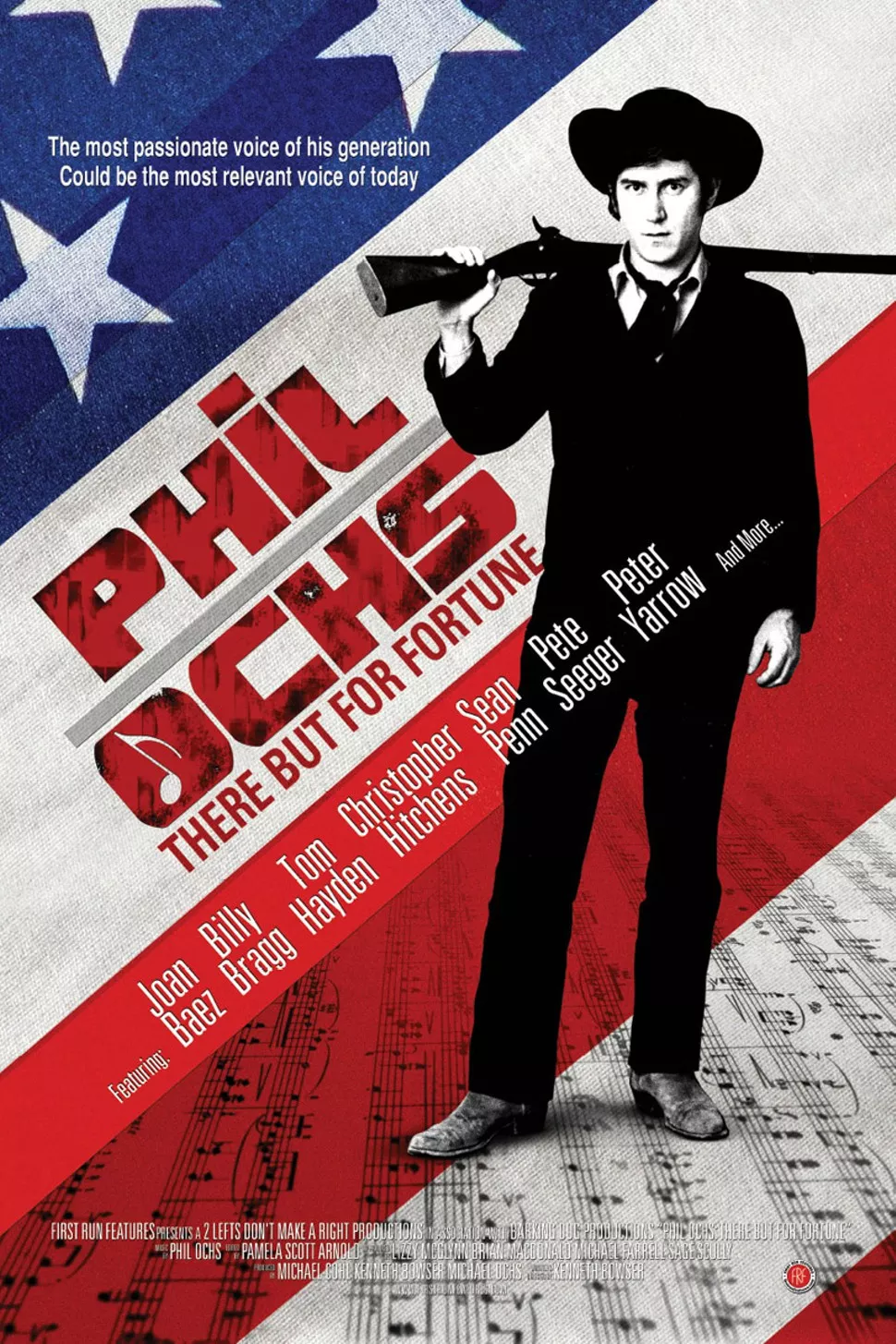

- First Run Features

- Phil Ochs (Los Angeles, 1968), as seen in Phil Ochs: There But for Fortune

By Mark Kemp

PHIL OCHS: THERE BUT FOR FORTUNE

***1/2

DIRECTED BY Kenneth Bowser

STARS Phil Ochs, Sean Penn, Christopher Hitchens, Joan Baez, Tom Hayden

In the liner notes to his 1965 album I Ain’t Marching Anymore, the late protest singer Phil Ochs addressed the emotional dichotomy of ego and responsibility, of his simultaneous desire for fame and his need to write and sing morally charged folk songs critical of a world gone mad.

“My vanity flutters as I hear again the cheers of audiences of thousands applauding …,” Ochs wrote, but then went on to say, “I realize that I can’t feel any nobility for what I write because I know my life could never be as moral as my songs.”

That psychic push and pull ruled Ochs’ fascinating and utterly complex life, a life that until now has never been fully explored onscreen. With Phil Ochs: There But for Fortune, filmmaker Ken Bowser rectifies this glaring omission in a documentary that covers it all, from the righteous, leftist, and very patriotic ballads and anthems Ochs sang at demonstrations and on college campuses, to the mental issues that hastened his alcoholism and ultimate suicide in 1976 at only 35 years old. The film premieres on PBS's American Masters at 10 p.m. Monday, Jan. 23, on WTVI in the Charlotte area.

Ochs was the preeminent protest singer of the 1960s. His musical marching order, “I Ain’t Marching Anymore,” became an anthem to anti-Vietnam war protesters the world over, but particularly in Ochs’ beloved United States of America. Ochs wasn’t just an anti-war singer, though. He was a musical journalist who sang the stories of nameless people who gave their lives to the civil rights struggle (“Too Many Martyrs”), of the plight of Mexican farm workers (“Bracero”), of labor organizers (“Joe Hill”), of an African-American journalist jailed for traveling to Cuba to report on Fidel Castro’s revolution (“The Ballad of William Worthy”). Ochs also sang musical editorials — on his respect for Jesus, the revolutionary (“Ballad of a Carpenter”), and contempt for Christianity, the religion (“Canons of Christianity”), and on his deep love and abiding hope for a more just U.S. (“The Power and the Glory”). Ochs could be vicious in his criticism. In “Here’s to the State of Mississippi” — about Old South racism and political corruption — he wrote, “Here’s to the land you’ve torn out the heart of / Mississippi, find yourself another country to be part of.”

Bowser’s There But for Fortune — named for Ochs’ tender song about poverty and desperation that Joan Baez turned into a 1965 Top 50 hit — begins with a disheveled Ochs in his final days, reflecting on his life and career, and then segues to a fresh-faced young Ochs crooning “When I’m Gone” on TV. It’s a poignant transition, as the lyrics proved sadly true following his suicide: “There’s no place in this world where I’ll belong when I’m gone,” he sang. “And I won’t know the right from the wrong when I’m gone / And you won’t find me singing on this song when I’m gone / So I guess I’ll have to do it while I’m here.” From there, the film flashes back and forth from archival footage to recent interviews with Ochs’ musical collaborators (Baez, Pete Seeger, Van Dyke Parks), political and intellectual allies (Tom Hayden, Ed Sanders, Christopher Hitchens), famous younger fans (Sean Penn, Billy Bragg) and family members (brother Michael and daughter Meegan), who tell his story — humorously, enthusiastically, compassionately — from the power and the glory of the singer’s fertile and idealistic years in the early- to mid-’60s to his sad emotional and mental decline of the early- to mid-’70s.Despite his relative obscurity today, Ochs was as much of a cultural and political spokesperson for his generation as his hero and sometime friend, Bob Dylan. Ochs was Bruce Springstein, Buck Owens, Bono, Steve Earle, Rage Against the Machine and Public Enemy combined. In his flawless croon with a hint of a country twang, he fearlessly spoke out about injustice with the same force that conservative firebrands on television project today. But there’s a huge difference between Ochs’ anger and today’s cynical TV rage: Ochs was keenly aware of his humanity — in some ways, too much so for his own good. He knew he didn’t have the answers, and when the Vietnam War ended with the unity of political commitment turning to selfish me-first consumerism, he lost his muse and desire to live. He became increasingly erratic, drinking heavily and even adopted a new, gruff personality that barely resembled the Ochs who years before had written a loving tribute to John F. Kennedy, “That Was the President.” On April 9, 1976, a beaten Phil Ochs hanged himself at his sister’s home in Far Rockaway, New York, his dreams — and ours — deferred, at best.

Fast-forward some 30 years later: The U.S. was in another war that its citizens overwhelmingly opposed, this time for oil in Iraq. The president was George W. Bush, not Lyndon B. Johnson or Richard M. Nixon. Few singers were speaking out: The Dixie Chicks made an attempt that backfired when ill-informed Americans went so far as to threaten the women's lives for speaking out against the president; Neil Young, an Ochs contemporary, recorded an album of Ochs-like protest songs. But few people were listening. Fast-forward another few years, and another group of Americans, spurred on by self-interested corporations and an entire TV network (FOX) set up solely to give voice to right-wing extremism, was expressing a different kind of moral frustration and indignation. But the Tea Party represented everything Phil Ochs opposed. And then finally, in more recent months, yet another group of frustrated Americans has risen up en masse, occupying town squares, court houses and city halls across the country. The Occupy Wall Street movement gave voice to the progressives and radicals who have been silenced for too long. Were he alive and healthy today, Ochs would likely be hunkered down alongside those "mobs of anger" and predicting the movement's proliferation as he did in this line from 1965, "And in city after city you know they will repeat / For these are the days of decision."

“My life could never be as moral as my songs,” Ochs wrote. Could you imagine Glenn Beck ever questioning his morality? Or Rush Limbaugh? Or Bono, for that matter? Self-awareness among cultural spokespeople is a rare quality, and those few who have had it, unfortunately, often struggled with demons. Kurt Cobain questioned the impact of his fame. John Lennon wondered, in song, “Who am I? What am I supposed to be?” And in one of Ochs’ most hauntingly beautiful late-period songs, he looked back on his life, confused and depressed: “My life was once a joy to me, / Never knowing I was growing every day… / My life was once a flag to me, / And I waved it and behaved like I was told… / My life is now a myth to me, / Like the drifter with his laughter in the dawn” — and finally — “My life is now a death to me.”

There But for Fortune is a powerful film about the triumphant life and tragic death of an American hero whose songs remain as timely today as they were when he wrote them. Too bad he’s not here to help us honor that life and continue the fight.

(Review originally appeared at the music website option-magazine.com)

Trailer: