Charlotte artists show support for cartoonists killed in Paris attack

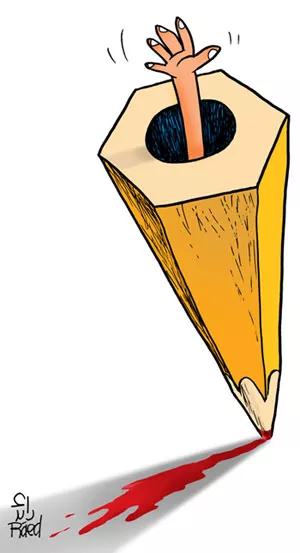

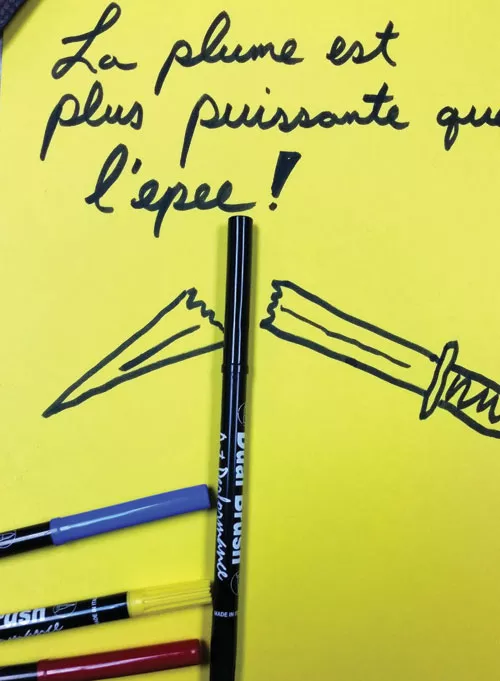

The pen vs. the rifle

By Kimberly Lawson @kimlawson22

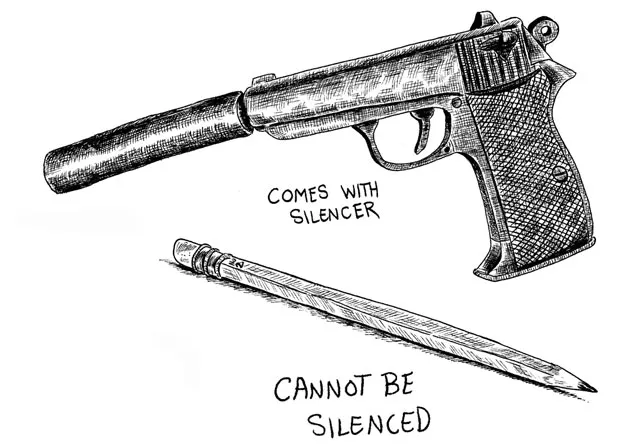

“I wanted, primarily, to show defiance to the idea that free human expression can be curtailed by violence. Violence is finite, it is containable. But human thought and expression, the things any person can make with a simple marking instrument, these things are eternal and cannot be contained or restricted no matter what power is weighted against them. I wanted to put these two tools side by side and illustrate, again, the power of the pen over the sword.”

Last week, two brothers stormed the offices of a satirical newspaper in Paris, France, and killed 12 people, many of them cartoonists and journalists. As reported by The Economist, Charlie Hebdo "was targeted because it cherished and promoted its right to offend: specifically to offend Muslims."

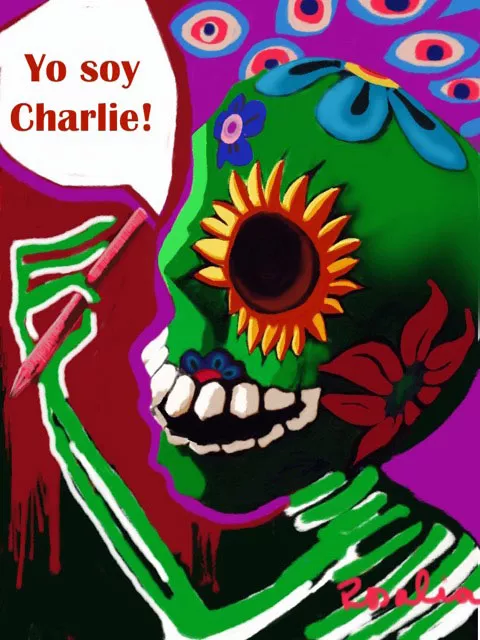

The world responded with sadness, outrage and hashtags: #JeSuisCharlie (I am Charlie), #JeNeSuisPasCharlie (I am not Charlie) and #JeSuisAhmed (I am Ahmed — the Muslim police officer who was killed by one of the gunmen). In Charlotte, cartoonists, artists and their friends showed solidarity with the murdered cartoonists by taking to the pen or taking photos with pens and posting their images on social media.

The conversations that have arisen since the attacks range from championing freedom of speech to reflecting on what's considered going too far. The words "ethnocentrism," "racism" and "radicalism" dot many of these online discussions, as does this uncomfortable question: "Did the journalists at Charlie Hebdo, so callous in their offensive depictions, bring the attack on themselves?"

"Those guys knew it was coming. They had been threatened for years," says Greg Russell, graphic designer and cartoonist for the Charlotte Business Journal. "Those guys were the bravest of the brave. They believed in free speech above all else, and they put their lives on the line for it. You have to admire that."

With satire comes a natural expectation of flack. But in terms of pushing the envelope, can an artist overstep his/her boundaries?

When Creative Loafing posted a call for art, amateur cartoonist and muralist Justin Teal submitted an illustration, which he says was meant to be as offensive as possible. So offensive, in fact, he himself was hesitant to publish it on social media. (We opted not to include his work in this story.)

But Teal says satirists should be able to explore any topic they choose without the threat of harm. "Fearing for your life for drawing a cartoon or making fun of someone or something is just insane. Those wackos out there that kill people over cartoons, bomb abortion clinics or shoot up schools and hide behind their warped version of any certain religion to justify doing horrific things ... those are the people who deserve to be made fun of, mocked and satirized into oblivion."

At the same time, he says, artists should recognize the difference between satire and "reasonless berating of a marginalized group or race."

CL's own go-to guy for political cartoons, Henry Eudy, calls satire "the great democratizer." He says he has "a real respect for any kind of art that can get its little dagger between the ribs of the viewer and twist it a little."

Kevin Siers, the political cartoonist for the Charlotte Observer and the 2014 Pulitzer Prize winner for editorial cartooning, admits he worries more about whether a cartoon of his goes far enough. "While certain images are deemed inappropriate for a 'family' newspaper, I can't think of any topic that's off limits — If there's something that needs to be said about a topic, there's usually a way, somehow, to draw it."

Russell, on the other hand, says he has no desire to offend anyone. "That just means you're mocking one group of haters' beliefs and shoring up another group of haters' beliefs. It perpetuates an 'us versus them' attitude, which is always dangerous and a lie."

Local painter Ráed Al-Rawi also works to avoid taking sides on any debate in his illustrated works. In the late '70s, he freelanced for major news publications in Baghdad, Iraq, during Saddam Hussein's regime. As one might imagine, Al-Rawi was particularly mindful of controversy. Even now (he moved to the U.S. in 1980 and publishes his work online) he's cautious.

"I think there is a fine line between critique and criticism," he says. "I aim for critique with a sense of satire instead of humiliating or making fun of the subject or a person."

Al-Rawi also points out turmoil stemming from the exercise of freedom of expression happens daily in the Arab world, but goes unnoticed in mainstream media.

At the heart of this tragedy is just that — a tragedy. By the time the two gunmen, 32-year-old Cherif Kouachi and 34-year-old Said Kouachi, were killed Jan. 9, the total number of victims of their, and a third gunman's, terror reached 17.

Siers says hearing about the Charlie Hebdo attacks was like reading a news report about a tragedy in the family. "Which, in a way, as the cartooning community's so small, it was. Emotionally, it was comparable to the shock of 9/11."

Other artists expressed similar shock, horror and sadness. Al-Rawi says as a Muslim, he felt shamed when he heard the news. "I do not practice the Muslim religion, but I know for a fact the word 'Islam' derives from the meaning of peace. Those killers do not represent Islam."

But those killers did allegedly shout "We have avenged the Prophet Muhammad" and "God is Great" in Arabic.

"I don't think the attack on Charlie Hebdo was about religion," says Siers. "It was an attack on free speech, free expression, an attempt to intimidate and silence opposing views."

For people who create, from writers and painters to musicians and actors, there is no greater freedom than that of expression. This week, the remaining staff of Charlie Hebdo printed 3 million copies of its next issue (up from its usual 60,000), featuring Muhammad holding a sign reading, "Je suis Charlie" with the tagline "All is forgiven." A teardrop lingers on his face.

"I thought a lot about what it means to strike out specifically against artists and writers with violence," says Eudy. "That draws attention to the real power of free expression, especially in imagery. Even a dumb, scratchy crayon drawing by an 8-year-old has this power. It conveys its information in an instant; it ridicules, it debunks, it rearranges reality, it changes minds, it affects every human that absorbs it, and it is absorbed just by being glanced at. That's something to fear, alright."

Speaking of...

Latest in Cover

More by Kimberly Lawson

-

Two Former 'CL' Editors Discuss the Hurdles of Increasing Diversity

Apr 26, 2017 -

Picky eaters need not join

May 27, 2015 -

O.N.E. Charlotte pushes for restorative justice in CMS

May 27, 2015 - More »

Calendar

-

Queen City R&B Festival & Day Party @ Blush CLT

-

Half & Half! @ CATCh

-

Cirque du Soleil: OVO @ Bojangles' Coliseum

Cirque du Soleil: OVO @ Bojangles' Coliseum -

200 Hour Yoga Teacher Training in Rishikesh India @ Arogya Yoga School

-

Sound Healing Course in Rishikesh