Sloane Siobhan (Photo by Dana Vindigni)

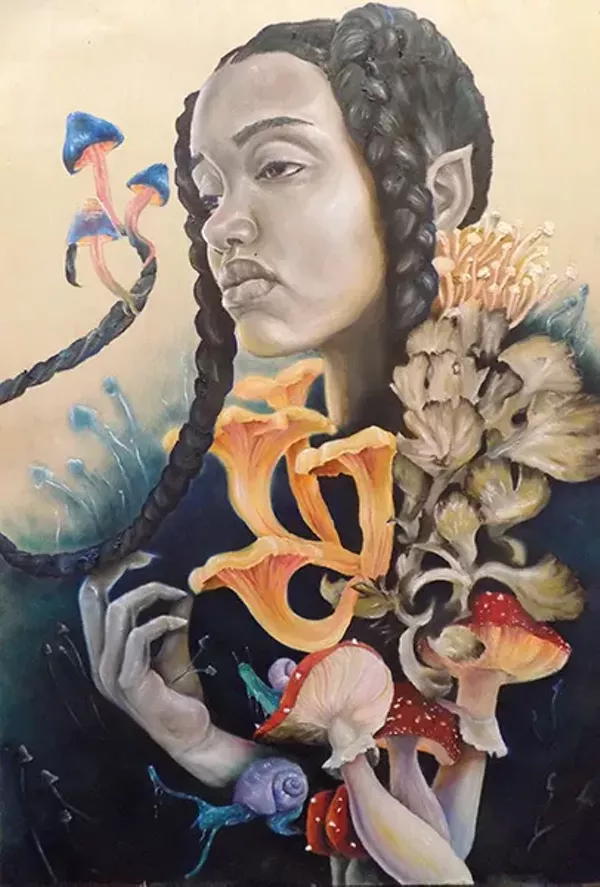

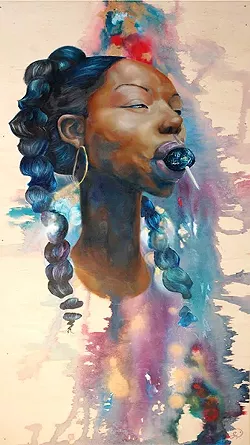

The young Artist is a bit like the black and brown fairyfolk in her paintings: reserved, mysterious even, her smile charged with a palpable sense of mischief. Black Girl Magic, the series of portraits Sloane Siobhan is currently creating, illuminates a corner of her studio with a quiet intensity. A full-featured, plaited and wistful woman rises from lush blooms. Only upon closer inspection do you note the elongated tapers of her fingers, the ears that come to a delicate point.

"There's this light I see in people," Siobhan says as she closes up shop at Studio Cellar off Camden Road and West Boulevard, where she works. "Everyone gives off this sort of essence about them and I just want to capture it — immortalize it, essentially."

The Black Girl Magic series is inspired by a particular demographic of society whose light is often overlooked or overshadowed. Siobhan calls her style Afro-futurism, but the nods to classical artists like Rembrandt are definitely apparent. She merges realism and abstraction, creating an order out of chaos, she says, because, "I feel like that's what black people do all the time. You might not have money to pay your bills, your job fucking sucks, but we still survive and thrive. We've got the sauce."

At 26, Siobhan, who graduated from Appalachian State University last December, definitely has the sauce. She looks to be on top of the world, actually. The rising Charlotte artist has an exhibit, Archetypes of the Subconscious, in the Harvey B. Gantt Center for African American Art through January; her work was featured in the Mint Museum Uptown this past fall; and she is regularly sought after for private commissions and creative collaborations, such as the November Feast Your Eyes CLT, a multi-course event that paired visual and culinary artistry. That same month, she was name-checked in a New York Post travel feature about North Carolina art.

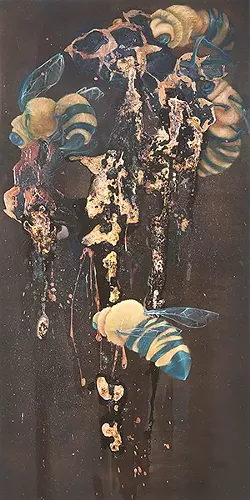

In her work, Siobhan pulls inspiration from themes and elements of fairy tales, animation houses like Studio Ghibli and comic books — anything fantastical — adding texture to her pieces with wood curls, gesso and inks.

"Alice in Wonderland, forests full of mushrooms, Pan's Labyrinth, steampunk — I try to switch it up a bit," she says. "I have a little darkness I like to explore. I'm almost like a god, creating this space, these worlds, these universes that exist in them, these people. Sometimes I dream up images. And then at some point I have to do it."

"Anyone who looks at her work is pulled in immediately," says Alexys Taylor, Collections and Exhibitions manager at the Gantt. "The way she takes pain and fantasy and transforms that into art is amazing."

Taylor hadn't heard of Siobhan before a chance conversation at a private event at Studio Cellar. "She mentioned she painted, which I appreciated because I love meeting artists," Taylor remembers. "Then she showed me her work and I saw it was on a whole other level. Her talent and skill level make [the Gantt] proud to learn she was born and raised in the Carolinas."

The Gantt Center is very long and narrow, with three galleries and less display space than one might expect. Taylor says exhibitions are planned about two years in advance, so it was a major coup for a rising artist to get work displayed only a few months after graduating.

"An opportunity came up for a small space on the exterior wall, and we offered it to her immediately," Taylor says "I was thrilled the Gantt could be a platform for her work."

Siobhan's career as an artist began when a preschool teacher told her mother, "Little kids don't color like this."

"I met her when she was about 4 and still have her drawing because, even then, she was exceptional," artist Jillian Goldberg, Siobhan's childhood instructor, remembers.

Right away, Reba Whaley, Siobhan's mother, became her biggest cheerleader, enrolling the youngster in art classes and later the prestigious Northwest School of the Arts. Whaley, a paralegal by day but also a frustrated writer, encouraged her daughter to pursue the arts with no compunction.

"She was really supportive," Siobhan says. "A lot of times, especially in black homes, they want you to go for the more practical occupations, but she was like, 'No, you're good at this, have fun with it. Don't worry about the money, the money will come.'"

Still, fear of becoming a starving artist drove Siobhan to begin college as a pre-med student. "I wanted to be a pathologist, or, if that didn't work out, a mortician. I'd always have a job," she says, laughing. "But I discovered about myself that if I don't want to do something, I'm not going to do it. It's hard; it takes way more drugs than I want to put in my body."

Whaley's death last year, from Stage 4 breast cancer, altered Siobhan's outlook on life. She moved back to care for her mother and had a hospice bed set up next to a wall lined with most of her artwork. She would sit with her mother and position her head toward the television, but after a while Whaley would turn away. It wasn't until after she'd passed that Siobhan realized her mother had chosen to look at her daughter's art while she was transitioning.

"She got to see me graduate, kind of," Siobhan remembers. "She was on her deathbed and the chairman of my arts college, my provost, the dean of students, and the graduation guard came down in a mock ceremony so she could see it. She wasn't super lucid, but that's the last time I can remember her smiling."

Siobhan sold her first piece to her alma mater, App State, for $800 plus copyrights. Though proud of the sale, she calls giving up rights to her work a mistake. "It was in the contract. I can post it anywhere but I can't make any prints of it," she says. "Art school is great, but you don't learn the business aspect of it and that part is very in-depth."

It was a lesson learned. After graduating, Siobhan started working events like Pancakes and Booze for exposure, but worried about devaluing her art. "It gets the job done if you sell prints, and if you're a commercial artist it's the way to go," she says. "But museum and galleries won't take you as seriously if you're too commonplace. Once I get into the Louvre, I'm selling all the T-shirts I want."

So far, Siobhan has made some strong mentorship connections, from serious art collectors to dealers to creatives like herself. Artist Marcus Kiser just wrapped Intergalactic Soul, his year-long residency at the McColl Center, and garnered national attention with a Miami-based public art series. He met Siobhan at one of the McColl's Open Studio events, but had been following her Instagram account, @namasteloner, for some time. Drawn by her talent and the fact that she was a native Charlottean, like him, Kiser introduced her to a number of local artists.

"People have the mindset that they can't do things or get to a certain level because they are from North Carolina," Kiser says. "But dope is dope, no matter where you are. Sloane is extremely talented, and anyone hungry and willing to get it, I support."

Community like this is a boost during those times when Siobhan could use the encouragement. "Charlotte is still kind of small, so the art scene is, too," she says. "We need more people who understand the importance of investing in art."

Siobhan says she'd like to see more public art around Charlotte, outside of the Uptown hub. "It wouldn't have to be like Venice Beach or anything, but there's a lot of wall space where art could benefit the neighborhood," she says. "People basically act like their surroundings, so if their area looks like trash, that's how they're going to behave. But if you come through and beautify it, and show people who look like you doing it, it really changes the morale."

She's been approached by her earlier alma mater, the Northwest School of the Arts, to create an installation in the school's newly renovated auditorium, and she's done several public murals in Raleigh and Cornelius. Though her reputation is growing fast, she's not close to her end goal yet.

"I'll know I've made it when they are teaching about me. I'm not there yet," Siobhan says. "Everybody knows DaVinci; he's made it. You work for however many years you're given and one day it's gone and if no one is here to remember it, that's it," she says. "That's the facts of it, that's why I want to be known. I promised my mom, I'll make sure no one ever forgets you. I just piggyback on her light."

Speaking of...

Latest in Cover story

More by Emiene Wright

Calendar

-

ANNIE LEIBOVITZ / WORK @ Mint Museum Uptown at Levine Center for the Arts

-

Trap & Paint + Music Bingo @ Blush CLT

-

Trap & Paint (Hookah Edition) @ Blush CLT

-

BookTok Sensation RC Luna Comes to Charlotte – Author Signing Event @ The Trope Bookshop

- Sat., Aug. 30, 11 a.m.-1 p.m.

-

R&B Sip & Paint + Comedy Show @ Blush CLT