Time Out Youth's Sanctuary for LGBTQ Kids Moves to Facility More Than Twice its Current Size

The safe haven

By Ryan Pitkin @pitkin_ryanIt's just after 3 p.m. on a Wednesday, and Grier, Asher and Dexter have all made it through another day of high school. That feels like a task for any teen drudging through the monotony of an endless series of school days, but for these three transgender boys, it's something more.

This trio has made it through another day of stares, passive-aggressive comments and the never-ending stream of questions regarding pronouns, sex and whatever else their classmates don't understand about them. They've made it through the strenuous school day and now they've entered the doors of the Time Out Youth Center (TOY), the only place they say they can be themselves.

The boys head straight for a bowl of snacks before grabbing a seat together on the couch, all rustling bags of Goldfish and other goodies. Asher says his Diet Mountain Dew tastes spicy, which is odd, although it probably has more to do with the bag of Doritos he was matching it with.

The group is joking and laughing nervously — still a bit reserved at the thought of a journalist with a voice recorder hanging out in their space — but beyond the jokes about snacks being the reason they come here is a clearer picture of the importance of a place like TOY in the lives of young people like these three boys.

"I wouldn't be as strong [without TOY]. Being in a space like this helped me understand that what I am is normal and there's nothing wrong with who I am," says Dexter, a 16-year-old junior. "I wouldn't have been as confident, as well, going into high school. I would feel some type of way, but I know that even if somebody [at school] says something that really does bother me, I can just come here and feel a lot better."

Dexter says he carries himself differently at school on days he knows he's coming to TOY, completing assignments with more enthusiasm and interacting better with the students around him on those days.

Dexter's friend Grier, a 15-year-old sophomore, says his life has also been changed by his time at TOY, where he began coming last February.

"I have become so much more confident in myself," Grier says. "If I'm ever just having a really bad day, I can come here and be with people who support me. Everything just turns out fine once you're here."

In the past year, spurred on partly by increased visibility in Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools and partly by fears regarding House Bill 2 and the election of Donald Trump, the number of kids seeking services from the LGBTQ youth advocacy organization nearly doubled.

The center saw 4,500 sign-ins in 2016, compared to 2,300 in 2015. Those numbers included kids like Grier and Dexter dropping by to hang out after school as well as young people who show up on the doorstep of TOY's current location in NoDa after coming out to their families and being kicked out of their homes, a relatively normal occurrence.

Services offered by TOY range from hang-out time and poetry night to support groups and one-on-one counseling.

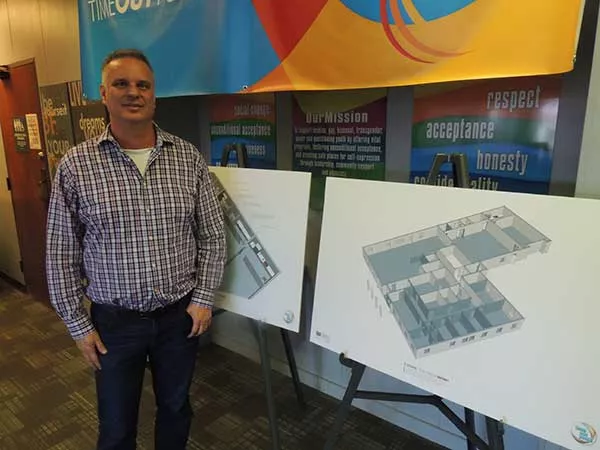

Earlier this month, TOY's staff announced the organization has purchased a new 7,400-square-foot building — about 2.4 times the space they currently rent out — on Monroe Road, which they aim to move into on April 9. Staff will then begin working toward goals of growth, including a transitional homeless shelter for LGBTQ youth.

The shelter would be one of many ways for TOY, which Board Chair Michael Condel says is "busting at the seams" at its current location, to expand and widen their base.

TOY will be renting out space in the new building to other LGBTQ organizations, helping to fund ongoing TOY services while also creating space for cooperation between the groups.

When TOY announced the purchase of the new building on Jan. 3, it also announced the beginning of a five-year capital campaign to raise $3.4 million for the center. While HB2-inspired donations from artists performing in North Carolina over the last year helped the center afford the down payment for its new space, the money raised will go toward the shelter and continuing to expand programs and services.

Within the next week, TOY is expected to announce a large donation to the campaign from a prominent Charlotte-area family that will help them reach half of their goal far ahead of schedule.

TOY was founded by Tonda Taylor, a member of a prominent 1950s Myers Park family who grew up knowing she was different. She moved to the more tolerant New York City in 1964 after feeling suffocated by the social expectations of Charlotte, but returned 20 years later when her brother Sam became infected with the HIV virus due to blood transfusions related to leukemia. Her father would also contract the virus, either through caring for Sam or blood transfusions during an earlier open-heart surgery.

Dr. Andrew Taylor took his own life shortly after getting the news, and seven months later, Sam passed away. HIV was seen strictly as a homosexual disease in those days, and the family faced harsh anti-gay criticism, despite the fact that neither Sam nor Dr. Taylor were gay. For Tonda, the experience recalled the pain of growing up gay in a conservative Southern city, and inspired her to want to help kids in a similar situation.

"She saw coming back to Charlotte as how to make a difference in the community by providing safe spaces," says Rodney Tucker, TOY's current exeutive director. "She realized there was nowhere for LGBTQ youth to go and be together, so she started a support group."

The group started with four people meeting on April 8, 1991, and over the years has grown in ebbs and flows. At last year's annual Time Out Youth Platinum Gala, at which the organization celebrated its 25th anniversary, TOY honored Taylor by naming two scholarships the center offers to area children after her. She still resides in Charlotte, and next week Tucker plans to bring her to see the new space — the first building owned by an LGBTQ organization in Charlotte's history.

Despite the overall success, TOY has hit its share of roadblocks over the years. In 2003, Adams Outdoor Advertising rejected Time Out Youth's potential billboard campaign that would have featured five billboards reading "It's OK to be gay" throughout Charlotte. The company claimed the billboard slogan sounded too "encouraging" and refused to place them.

While that incident was frustrating for the TOY team, it was nothing compared to the more urgent issues faced by youth that the staff encounters on a near-daily basis. Some of those issues can be life-or-death, and they sometimes validate the importance of the work TOY is doing, says Condel.

"Not all the stories are success stories. We've had some of our transgender youth that have committed suicide. Hearing those stories also helps you understand the importance of your work," Condel says. "It's not all the good things that happen, but it's also the devastating stories that you hear about kids being bullied at school, kids having their parents kick them out of their home and them showing up with their luggage here, that really kind of affirms the importance."

In early 2015, the center was faced with a worst-case scenario when four teens who regularly attended TOY took their own lives within a three-month period. The group included Ash Haffner, 16, who had been struggling with whether they identified as a lesbian or a transgender male. On Feb. 26, Haffner stepped in front of a car on a busy road near their Union County home.

In a journal entry later found on Haffner's iPad, they wrote, "don't be so quick jumping to labels. My pronouns do not define me. but when you ask me if i'm a boy or a girl, i don't know how to answer."

About a month later, on March 23, Blake Brockington, another regular at TOY, took his own life. Brockington was an 18-year-old trans man who was beloved in the activist community. He made national headlines in 2014 when he was named homecoming king at East Mecklenburg High School, the first trans person ever to receive such a title in North Carolina.

The Suicide Prevention Resource Center estimates that between 30 and 40 percent of LGBTQ youth have attempted suicide. The TOY staff was already well aware of the vulnerabilities of the community they served, and had lost clients before, but the string of suicides in 2015 rocked the Time Out family, leading some of the staff to question everything they had been doing.

"It was the saddest I've ever been in this space, with people being worried, parents being worried that this could happen to my child, staff being worried how does this reflect back," Tucker says. "When that many friends die in a short period, it becomes a very real thing — a problem to answer."

TOY began creating new programming for trans youth and hired a trans outreach coordinator, a first for the state. Among other services, TOY now hosts Tea Time on Thursday nights, a discussion space for transgender, non-binary and questioning youth. Dexter says attending the group is one of his favorite parts of coming to TOY.

While TOY staff has become better at handling issues facing the young LGBTQ community, the facility is only open for a few hours each day. The staff doesn't take time off when the kids aren't around, however. They're often working to educate others who come into contact with LGBTQ youth on a regular basis about how to work with them on a professional basis.

Staff has carried out professional development training with employees of Carolinas Medical Center and Novant Health; they've trained every counselor with Cardinal Innovations, the state's largest mental health provider; and last year Todd Rosendahl, TOY's director of school outreach, trained 4,000 employees of Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools.

It is with the school system that TOY works closest to do outreach for kids who may be in need of services. Its staff serves as lead consultants for any LGBTQ issue that arises in schools. They will speak to administration if there is an issue with bullying or between a student and a teacher. In the past year, both Grier and Dexter said TOY stepped in to ensure they would be called by their proper names and pronouns, making them feel more comfortable in school settings.

"When I was having problems with school — because my school administration is kind of bad — they helped with everything," Grier says. "It felt so good because I didn't have any advocates at my school. They were able to go in and advocate for me."

As Time Out Youth continues to cement its relationship with local schools — and branch out into school systems in surrounding counties — the organization has also found success in reaching out to places where LGBTQ youth also unfortunately find themselves all too regularly: local homeless shelters.

In February, TOY staff will begin training employees and volunteers at the Men's Shelter of Charlotte. That's something TOY has wanted to do for decades. "It's taken us 25 years to get to this place, so we're excited," Tucker says.

Condel believes a national needs-assessment study TOY conducted in 2015 and released in September 2016 — which found, among other revelations, that LGBTQ youth make up 40 percent of the homeless population in some large urban areas — finally inspired shelters to want to work with them.

"The study that we did showed that the youth don't feel comfortable in the men's shelter or women's shelter, and a lot of the shelters don't know how to deal with the differences in the LGBTQ population," he says. "So you have the youth that are concerned and don't feel safe and you have staffing that doesn't have the right level of support that's out there."

In recent years, TOY has done what it can to help transition homeless LGBTQ kids off the streets without the need of outside shelters. Every year, through its Home Host Program, TOY helps about 10 homeless LGBTQ youth find full-time jobs and move into their own places within 90 days, all while living with volunteer families that pay for their groceries and provide transportation over those three months.

The program has seen a 100-percent success rate, and recent partnerships with companies like Food Lion, Chipotle and potentially Target have helped case managers get kids into the workforce quickly. But there are still obstacles.

Due to the nature of the volunteer hosting program, youth who have been suicidal, in a mental institution or in jail during the last year aren't able to live in volunteers' homes. While case managers still work with those youths to help them find work and a new home, the instability of not having immediate housing can make things difficult.

Now, with the construction of a transitional homeless shelter, which Tucker hopes to see completed by 2020, TOY will be able to help more at-risk youths.

Tucker spends countless hours helping homeless young people. He says the center receives four to five calls a week from young people who need assistance because they're expecting to be kicked out of their homes. It never gets any easier, he says.

"They show up here with nothing, it's the saddest thing. I've never known someone to get rid of a child like that. They come to us really broken. To put them back together and give them support, there's a lot of trust that you have to build with our staff; trust with the new family . . . Everybody has to believe together; it's a lot of work," Tucker says.

Yet it's all in a day's work at Time Out Youth. One thing that's clear when you spend time at the facility is that the young people there truly do come first. Youths make-up 15 percent of the board, which has led to disagreements in the past. For example, youths led a charge to include "Q" at the end of "LGBT" in the TOY mission statement and were ultimately successful. They're efforts to change a policy regarding smoking on facility grounds were less so.

"They get the professional experience and the interaction with the board members, and sometimes we do change our vantage point on what polciies and procedures we make, but sometimes we just cant do that," Condel says. "But they can see then why we made the decision to do it, so it's easier to go back to the other youths and say, 'I was there for the decision and this is what the board was saying.'"

Also, each potential TOY employee has to go through an interview with the youths being served there, during which questions can range from potentially life-or-death scenarios to what type of cheese the applicant likes. Before a new employee is hired, staff and youth must come to a consensus on the decision, and oftentimes it's the young ones who will call the applicant with the good news.

"We stay really focused on our kids. We're training kids to be advocates; to advocate for themselves and to advocate for others," Tucker says. "We're trying to train our kids to stand up for themselves, stand up for others, to do what's right and be kind. I think the whole bottom line of this agency is showing love to people that might not seek or get love all the time, and so that's kind of the core of what we're doing."

Safe to say that's a smart investment in today's world.

Speaking of...

-

Local Center Provides Pathways to Stability for Homeless Youth

Sep 19, 2018 -

Varsity Kinks

Sep 5, 2018 -

Billy Graham's Other Legacy

Feb 21, 2018 - More »

Latest in Cover

More by Ryan Pitkin

-

You're the Best... of Charlotte

Oct 27, 2018 -

Listen Up: Cuzo Key and FLLS Go 'Universal' on 'Local Vibes'

Oct 25, 2018 -

Listen Up: KANG is Back and Bla/Alt on 'Local Vibes'

Oct 18, 2018 - More »

Calendar

-

Queen City R&B Festival & Day Party @ Blush CLT

-

Half & Half! @ CATCh

-

Cirque du Soleil: OVO @ Bojangles' Coliseum

Cirque du Soleil: OVO @ Bojangles' Coliseum -

200 Hour Yoga Teacher Training in Rishikesh India @ Arogya Yoga School

-

Sound Healing Course in Rishikesh