Film Reviews

Tuesday, October 30, 2012

Film / Film Reviews Halloween Countdown: Vampyr

Posted By Matt Brunson on Tue, Oct 30, 2012 at 2:00 PM

(In anticipation of the coolest day of the year, this month-long series will offer one recommended horror flick a day up through Oct. 31.)

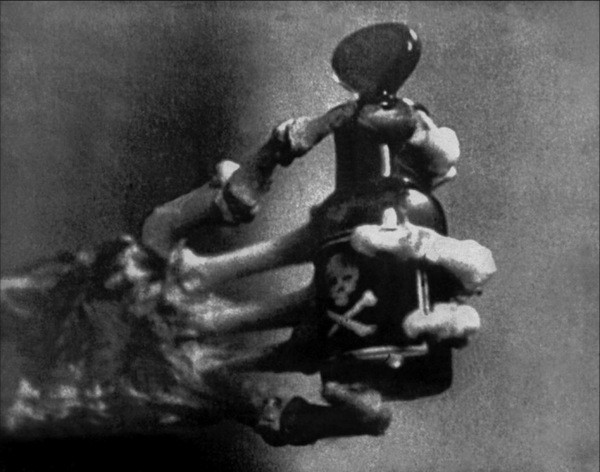

VAMPYR (1932). The notion of cinema as dreamscape has rarely been realized as exquisitely as in Danish writer-director Carl Theodor Dreyer's moody vampire tale. Loosely based on Sheridan Le Fanu's story "Carmilla," the movie carries all the logic of a restless sleep filled with surreal thoughts, many of which tip into pure nightmare. Baron Nicolas de Gunzburg, the film's financier, adopted the pseudonym Julian West to portray the movie's leading character of Allan Gray, a young man who shows up in a European village rumored to be housing a vampire. The bloodsucker turns out to be an elderly woman named Marguerite Chopin (Henriette Gerard), and she's aided in her dastardly deeds by the local doctor (Jan Hieronimko). Also figuring into the proceedings are an estate owner (Maurice Schutz) and his two daughters (Sybille Schmitz and Rena Mandel), one of whom has already fallen under the spell of the vampiress. Vampyr was Dreyer's first sound film, yet not surprisingly, it plays like a silent feature, with the emphasis on visuals rather than dialogue. And what visuals! There are images here that are staggering in their artistry: the shadow of a one-legged servant separating from its owner and taking off on its own; a ferryman wielding a scythe next to a fog-encrusted lake; the ultimate fate of the doctor, undone by (spirit-assisted) machinery even more imposing than the wheels and cogs encountered by Charlie Chaplin in Modern Times; and the POV shots that find a prematurely boxed Gray witnessing the activities occurring just above the glass window on his coffin. For all its accomplishments, the movie can't match F.W. Murnau's 1922 Nosferatu (still the greatest of all vampire films), but its atmosphere of pervasive evil retains its power to grip viewers.

Monday, October 29, 2012

Film / Film News / Film Reviews Savannah Film Festival: Chapter 1

Posted By Matt Brunson on Mon, Oct 29, 2012 at 9:00 PM

While I’ve managed to avoid spending midnight in the garden of good and evil, my trip to the 15th Annual Savannah Film Festival has found me spending all hours in the theater of good, average and exceptional cinema.

- Photos by Natalie Joy Howard

OK, so a grasping reference to a literary work that’s almost two decades old might not seem like the hippest way to open a piece, but consider that John Berendt’s Savannah-set blockbuster novel still gets a lot of mileage in this Georgia town, as evidenced by this store display (statues, paperbacks, audiobooks, DVDs and CDs) my wife Natalie and I spotted just this afternoon:

In fact, as preparation for our jaunt to this festival — a prestigious and renowned event presented annually by the Savannah College of Art and Design (SCAD) — we re-watched Clint Eastwood’s 1997 film version of Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil the night before leaving home. Of course, our actual experience has proven to be nothing like the movie: We haven’t been invited into the home of one of the city’s nouveau riche, we haven’t seen any men walking invisible dogs or tying bees to their body, and we haven’t become BFFs with local drag legend The Lady Chablis (although we did spot a poster announcing her upcoming show dates).

No, our experience has actually been better.

Film / Film Reviews Halloween Countdown: The Fly

Posted By Matt Brunson on Mon, Oct 29, 2012 at 2:00 PM

(In anticipation of the coolest day of the year, this month-long series will offer one recommended horror flick a day up through Oct. 31.)

THE FLY (1986). For nearly four decades, David Cronenberg has ranked as a maverick filmmaker who marches to his own beat, so it's with no small measure of irony that his best picture also turns out to be his most commercially successful one. The minor 1958 sci-fi classic The Fly is re-imagined by Cronenberg so that it fits more snugly with his favorite themes: the relationship between man and machine, the draw of sexual perversities, and the manner in which our own bodies can betray us without a moment's notice. Yet for all its fetishistic attention to gross-out elements, what primarily distinguishes the film is its love story; I've seen this movie approximately a dozen times, and the tragic romance never fails to choke me up. Jeff Goldblum is sensational as the doomed scientist who notes, "I'm an insect who dreamed he was a man and loved it. But now the dream is over and the insect is awake" — an aching, beautiful passage. He's matched by Geena Davis, cast as the journalist who's tormented by what's happening to the man she adores. Chris Walas and Stephan Dupuis deservedly earned the Oscar for Best Makeup; Walas then assumed the role of director for 1989's The Fly II, one of those sequels requested by absolutely no one.

Film / Film Reviews Halloween Countdown: Week 4 Recommendations

Posted By Matt Brunson on Mon, Oct 29, 2012 at 10:00 AM

(In anticipation of the coolest day of the year, this month-long series will offer one recommended horror flick a day up through Oct. 31. Here are the films that were selected Oct. 22-28. Click on the title to be taken to the review.)

Oct. 22: Spider Baby or, The Maddest Story Ever Told (1964)

Oct. 23: The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974)

Oct. 24: The Descent (2006)

Oct. 25: The Howling (1981)

Oct. 26: Dracula: Pages from a Virgin's Diary (2002)

Oct. 27: The Orphanage (2007)

Oct. 28: Black Sunday (1966)

And here are the Week 1-3 picks:

Oct. 1: Day of the Dead (1985)

Oct. 2: Brotherhood of the Wolf (2001)

Oct. 3: The Thing from Another World (1951)

Oct. 4: Count Dracula (1970)

Oct. 5: Cat People (1942)

Oct. 6: Homicidal (1961)

Oct. 7: The Phantom of the Opera (1925)

Oct. 8: Piranha (1978)

Oct. 9: Willard (2003)

Oct. 10: House of Wax (1953)

Oct. 11: Dead Alive (1992)

Oct. 12: "Manos" The Hands of Fate (1966)

Oct. 13: Island of Lost Souls (1932)

Oct. 14: The Body Snatcher (1945)

Oct. 15: The Host (2006)

Oct. 16: I Walked with a Zombie (1943)

Oct. 17: Kingdom of the Spiders (1977)

Oct. 18: The Mist (2007)

Oct. 19: Horror Express (1972)

Oct. 20: Phenomena (1985)

Oct. 21: Slither (2006)

Sunday, October 28, 2012

Film / Film Reviews Halloween Countdown: Black Sunday

Posted By Matt Brunson on Sun, Oct 28, 2012 at 2:00 PM

(In anticipation of the coolest day of the year, this month-long series will offer one recommended horror flick a day up through Oct. 31.)

BLACK SUNDAY (1966). Italy’s Mario Bava made his official directorial debut — he had worked uncredited on several earlier titles — with Black Sunday (aka The Mask of Satan), a beautifully composed picture whose moments of genuine shock surely rattled many a patron back in the day (indeed, the movie was banned in England for many years). Barbara Steele, in the role that turned her into a horror film icon, plays Asa, a 17th century witch who swears vengeance as she's burned at the stake. Cut to two centuries later, and a revived Asa schemes to gain immortality by drinking the blood of her descendant (also Steele). Bava and his crew's employment of unique camera angles, heavily atmospheric sets and startling moments of violence combine to create a trendsetting picture that has influenced generations of filmmakers (including Martin Scorsese and Tim Burton).

Saturday, October 27, 2012

Film / Film Reviews Halloween Countdown: The Orphanage

Posted By Matt Brunson on Sat, Oct 27, 2012 at 2:00 PM

(In anticipation of the coolest day of the year, this month-long series will offer one recommended horror flick a day up through Oct. 31.)

THE ORPHANAGE (2007). Juan Antonio Bayona's directorial debut arrived with the "Pan's Labyrinth Seal of Approval" — that is to say, it received the blessing of Pan writer-director Guillermo del Toro by way of a "produced by" credit — and it's clear it deserved the lofty honor. Frequently, the screenplay by another newbie, Sergio G. Sanchez, seems like it's merely a compendium of stellar moments from other horror hits: In addition to Pan, there are elements that strongly recall The Devil's Backbone (also by del Toro), The Others, The Innocents, The Omen and — I hesitate to add — Friday the 13th. Eventually, though, the homages coalesce to create a deeply absorbing and heavily atmospheric yarn that offers several noteworthy plot spins. In a commanding performance, Belen Rueda stars as Laura, who returns to the now-abandoned orphanage where she was raised as a child. With her husband Carlos (Fernando Cayo) and adopted son Simon (Roger Princep) in tow, she moves into the building with the hopes of reopening it in order to serve ill and handicapped children. But the bumps in the night begin almost immediately, with Simon insisting that anything abnormal is being caused by his new imaginary friends. As Laura digs deeper, she learns that the unusual circumstances tie back to incidents that occurred around the time she herself was a young girl residing at the institution. There are a few moments that employ the tried-and-true shock technique, but for the most part, Bayona expertly builds upon the unsettling sense of menace that's established from the start.

Film / Film Reviews Weekend Film Review: Cloud Atlas

Posted By Matt Brunson on Sat, Oct 27, 2012 at 11:03 AM

Click on the title to be taken directly to the review.

Also, be sure to check out our ongoing Halloween Countdown series; all films to date found conveniently here.

Friday, October 26, 2012

Film / Film Reviews Halloween Countdown: Dracula: Pages from a Virgin's Diary

Posted By Matt Brunson on Fri, Oct 26, 2012 at 2:00 PM

(In anticipation of the coolest day of the year, this month-long series will offer one recommended horror flick a day up through Oct. 31.)

DRACULA: PAGES FROM A VIRGIN’S DAIRY (2002). Not since Francis Coppola's sharp take on Bram Stoker's Dracula has there been a vampire flick as deliriously off the wall as Guy Maddin's Dracula: Pages from a Virgin's Diary. Produced for Canadian television and featuring the Royal Winnipeg Ballet, this film brings the dance form alive on screen, at once making it sexy, stylish and relevant. Yet this isn't merely a filmed stage performance — most of the time, the dancing is so minimal that you forget you're even watching a ballet. Instead, Maddin has integrated a new reading of the text with an old-fashioned shooting style straight out of the silent era. Influenced by the 1922 classic Nosferatu, this version employs black-and-white film stock (with the occasional striking burst of color), simple title cards and often overripe performances to convey the cinematic experience of a century ago. Yet where Maddin (working from Mark Godden's stage show Dracula) ventures out on his own is in his casting of Zhang Wei-Qiang as Dracula — conveying the fear the Western world often exhibits toward immigrants from the East — and in his portrayal of the so-called good guys as humorless puritans straight out of Arthur Miller's The Crucible. The rigidity of Dr. Van Helsing (David Moroni) is far more disturbing than the sensuality of Dracula and his brides, and it's no coincidence that the dancers are most alive after they've been involved in a little neck-nibbling.

Thursday, October 25, 2012

Film / Film Reviews Halloween Countdown: The Howling

Posted By Matt Brunson on Thu, Oct 25, 2012 at 2:00 PM

(In anticipation of the coolest day of the year, this month-long series will offer one recommended horror flick a day up through Oct. 31.)

THE HOWLING (1981). The best of the three werewolf pictures released in the same year — the others (both good) were An American Werewolf In London and Wolfen — The Howling is one of those rare horror flicks that successfully manages to integrate some humor into the proceedings without detracting from the terror elements. For that, we can thank director Joe Dante and scripter John Sayles, who both tweak the genre while still maintaining an obvious reverence; E.T. mom Dee Wallace, who delivers an excellent performance as a TV news reporter who unwittingly ends up at a resort populated by a werewolf colony; and makeup artist Rob Bottin, responsible for the astonishing transformation scenes. Made for $1 million, this grossed $18 million and led to seven schlock sequels, none of which had anything to do with this class act. A top-notch werewolf flick on its own, this offers added appeal to film buffs, who will catch the brief appearances by horror-movie mainstays (including John Carradine, Dick Miller and Famous Monsters of Filmland editor Forrest J Ackerman) and the fact that most of the characters are named after directors of previous wolfman pictures.

Wednesday, October 24, 2012

Film / Film Reviews Halloween Countdown: The Descent

Posted By Matt Brunson on Wed, Oct 24, 2012 at 2:00 PM

(In anticipation of the coolest day of the year, this month-long series will offer one recommended horror flick a day up through Oct. 31.)

THE DESCENT (2006). Not only did writer-director Neil Marshall's The Descent make my “10 Best” list for 2006, it also continues to rank as one of the finest horror flicks of the new millennium. The story follows six outdoor enthusiasts — all female — as they embark on a spelunking expedition deep in the Appalachian mountains. The competitive Juno (Natalie Mendoza) leads the outfit while Sarah (Shauna Macdonald) tries to overcome a recent tragedy in her life; along with the others, they descend deep into a cavern that's frightening even before its cannibalistic occupants (who look like Gollum's cousins) show up and start tearing into human flesh. The Descent is is so expertly made that it more than holds its own as a full-throttle horror flick, yet it's Marshall's decision to provide it with a psychological bent that puts it firmly over the top. Guilt — or, more specifically, survivor's guilt — is rarely addressed in movies of this kind, yet from its opening tragedy to a shocking incident that occurs halfway through the film (you won't see this coming), the film imbues its female protagonists with messy moral dilemmas that allow them to alternate between heroine and villain, survivor and victim, wallflower and warrior. In fact, there's so much baggage attached to two members of the group that we occasionally forget the other, more immediate menace on hand. But then the teeth start gnashing and the blood starts flowing, and in an instant, we remember all too well.