American history X

How the Kinsey exhibit at the Gantt Center fights the "myth of absence"

By Mary C. Curtis @mcurtisnc3"Any Person May Kill and Destroy Said Slaves," reads an arrest proclamation from 1798. Issued for "Jem" and "Mat" by Warren County, N.C., it may as well have been a death sentence. Even if Jem and Mat, two escaped slaves, were able to get to the North to a state that had abolished slavery, they would still be in danger. A clause in the U.S. Constitution guaranteed the right of a slave owner to recover his or her "property," and the Fugitive Slave Act signed into law by George Washington in 1793 that made it a federal crime to help an escaped slave.

Another document, from 1907, details the North Carolina law "Providing for the Separate Accommodation of White & Colored Passengers Upon Motor Busses, and for Other Purposes."

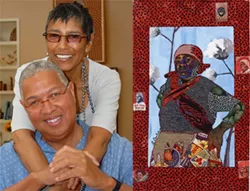

The documents are part of The Kinsey Collection: Where Art and History Intersect, which is showing at the Harvey B. Gantt Center for African-American Arts + Culture until October. The more than four centuries' worth of art, historical documents, photographs and artifacts that Bernard and Shirley Kinsey have gathered in more than 40 years of marriage shine a light on what can't be denied or extinguished: African-American sacrifice and achievement is part of American history, not just African-American history.

But much of the collection is history some would rather ignore or wish away. That cannot happen, though, because, "we've got the goods," as Bernard Kinsey told me during his visit to the Gantt to open the show in June. "We've got the documentation."

The Kinseys, both Florida natives, met as students at historically black Florida A&M University in Tallahassee, where they participated in civil rights demonstrations. They built careers at Xerox and collected work from mostly African-American artists. (Bernard likes to say that he collects "dead" artists and his wife "living" ones.) Then, about 26 years ago, Bernard came into contact with a slave's bill of sale, found in an attic, which led the couple to focus on finding African-American historical documents. Bernard told me that many relics come from attics and are offered for sale to him by those who have heard of his passion. That original bill of sale can be seen in the collection at the Gantt.

After a few successful real-estate investments and a lucrative career, Bernard retired at 47. The Kinseys have spent their time and energy sharing the collection and raising money — more than $22 million — for charities and scholarships for students to attend historically black colleges and universities.

The collection features photographs of black Civil War soldiers, who suffered casualty rates greater than other troops; the 1796 "Almanack" of Benjamin Banneker, the African American known as the "Sable Astronomer," who predicted solar and lunar eclipses and assisted in the first survey of the boarders of the original District of Columbia; an early copy of the Emancipation Proclamation; and a program from the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, held in 1963. The evidence of excruciating injustice and cruelty featured in the collection should not be hidden away in shame — it's a sign of resilience and survival.

The show also contains paintings and sculptures, some by North Carolina artists, including Charlotte-born Romare Bearden and Charles Alston and Gastonia's John Biggers. But here, too, are stories of struggle, as some of the aforementioned artists had to leave their home state or the country for opportunity and the recognition and compensation that still seldom approached that of their white contemporaries.

The collection helps reshape the narrative of America, correcting what Bernard calls the "myth of absence" — the myth that African Americans weren't involved with the United States' history and development.

At the Gantt Center, the Kinsey Collection follows the success of Tavis Smiley's "America I AM: The African American Imprint," which filled the museum last year.

The collection couldn't come at a better time. With the recent Supreme Court ruling that threw out a key provision of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 — and paved the way for discriminatory voting changes unfettered by federal pre-clearance — North Carolina and other states are rushing to pass voter-ID and other laws that ignore the hard-won progress traced on the walls of the Gantt. A lithograph shows seven men, "The First Colored Senator and Representatives in the 41st and 42nd Congress" from 1872, during the brief time when African Americans gained the voting franchise after the Civil War and before the harsh reality of Jim Crow took it away in many states. As legislators try to roll back time, the Kinsey Collection shows the fight it took to move slowly forward.

It also shows that more Americans are celebrating African-American history as American history, no hyphens necessary.

Curtis, an award-winning Charlotte-based journalist, is a contributor to The Washington Post's "She the People" blog, theGrio and the Women's Media Center. Her "Keeping It Positive" segment airs Wednesday mornings on WCCB News Rising Charlotte, and she was national correspondent for Politics Daily. Follow her on Twitter: @mcurtisnc3.

Speaking of...

Latest in News Feature

More by Mary C. Curtis

-

Charlotte Squawks really does meet SNL - just look at the cast

Jun 19, 2014 -

Madam C.J. Walker: She had a dream

Jan 29, 2014 -

Broadway comes to Charlotte, courtesy of an almost native son

Nov 11, 2013 - More »

Calendar

-

Cirque du Soleil: OVO @ Bojangles' Coliseum

Cirque du Soleil: OVO @ Bojangles' Coliseum -

Coveted Luxury Watches

-

TheDiscountCodes

-

Queen City R&B Festival & Day Party @ Blush CLT

-

R&B Music Bingo + Comedy Show @ Blush CLT