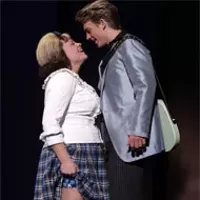

Dealing with the question of why Beth and Tom fail where their friends succeed, Margulies is far more oblique. We flash back at the top of Act II to the afternoon when Karen and Gabe first brought Beth and Tom together at their Martha's Vineyard summer home. In nonchalant Chekhovian fashion, we see exactly how flimsy the underpinnings of Beth and Tom's relationship really are.

Shuttling back to the aftermath of her marriage, we watch Beth over a patio lunch with Karen excitedly explaining how eager she now is to marry Tom's legal associate. Deja vu? Karen inquires, sparking Beth's resentment. Later that same afternoon, we see that the divorce has also weakened the friendship between Tom and Gabe, as Tom presents a disarmingly objective postmortem analysis of his marriage, casually revealing how little conviction and commitment he brought into it.

That friendship was love, Gabe realizes in the final bedroom scene that deftly echoes the original Martha's Vineyard quadrille. Now it's the fragile underpinnings of Karen and Gabe's marriage that are clinically exposed. But Gabe brings his ethos of commitment to the table -- and a mechanism for restoring intimacy when the relationship teeters on the edge of the abyss. Dopey as that shtick is, it works.

All of this somehow skirts solemnity because of the comical quirks distributed among Margulies' characters and the tasty ironies of their fates. In Act I, Tom is still getting better sex from his estranged wife than Gabe is getting from his contented one. As the curtain goes down in Act II, Karen and Gabe are more torn up over their friends than Beth and Tom are themselves.

Production is every bit as slick as the Pulitzer Prize-winning script, with silky smooth scene changes from Frank Ludwig's nifty Danish modern set design, and spot-on lighting from Eric Winkenwerder. Other than not decreeing a paunch for Gabe, Terry Loughlin's stage direction is flawless.

Smith shows us a wholesomeness and goofball energy we've never seen from him before, leaving none of Gabe's piquant double entendres unsavored amid his stoical suffering. Koon gives exactly the right weight to Karen's judgmental deficiencies, balancing them beautifully against her perky gourmand savoir faire.

Karla Mason makes a superb Rep debut as the artsy-flaky Beth, swerving credibly from gaiety to tears in the opening scene, and veering flamboyantly afterwards from rage and resentment to effervescence and euphoria. While Tom is the most freewheeling and disruptive among the quartet of principals, he's also in some ways the most secure and sensible. Rob Trevelier makes the role fun, imbuing Tom with an affable, plain-spoken boldness and a fastidious conceit.

Unlike last month's True Home, there's nothing embryonic here. I cordially invite you to Dinner. It's a winner.

Tom Vance can't remember whether he began directing fall musicals at CPCC back in 1967 or 1968. But the current Joseph and the Technicolor Dreamcoat is definitely the Vance valedictory, as Charlotte's senior producer director turns his creative energies exclusively to CP Summer Theatre.

Commercially and artistically, Vance is going out on a high note. The Andrew Lloyd Webber-Tim Rice crowdpleaser is already sold out for the entire run, a historic CP first. And Joseph is familiar terrain: Vance directed a sparkling summer version in 1993 and prepared one of the local kiddie choruses that participated in the touring version at Ovens Auditorium a few years later.

The artistic team behind the scenes is as strong as ever. Linda Booth has freshened the choreography. Costumer Bob Croghan has mixed in contemporary play clothes, warm ups, and S&M garb amid the usual explosion of Israelite color and Egyptian glitz, tossing in a couple of cutesy camel suits. Vance himself has tossed in a couple of new wrinkles in Pharaoh's Elvis shtick and now has music director Drina Keen taunting Joseph's starving brethren, brandishing a turkey drumstick like a baton at the height of the "Old Canaan Days" lament.

As expected, Steve Bryan is a hoot as Pharaoh, and the brothers, spearheaded by Patrick Ratchford as Ruben, are a winsome ensemble. The only disappointment was Rachelle Howell's self-conscious Narrator, straining to hit the high notes and becoming unintelligible when she did.

As Joseph, Kevin Jayroe simply blows away any memory you might have of his Charlotte predecessors -- teen idol Tommy Page at CP or Sam Whats-his-name on tour at Ovens. Jayroe sings, dances, and acts better than either of them, and his bare torso had my wife unabashedly drooling.

On my third go-round with The Baltimore Waltz, I'm beginning to get the hang of Paula Vogel's cockeyed tribute to her dead brother. Partial thanks go to Off-Tryon Theatre Company artistic director Glenn Griffin, who imposes a ritualized presentation upon the picaresque story and inserts a phantasmagorical interlude between our protagonist's fantasy and her rocky landing back in the reality of AIDS.

Onstage, Sheila Snow deserves equal credit, discarding her customary sexy smirk in favor of a dowdy diffidence that makes Vogel's surrogate, elementary school teacher Anna, seem suddenly plausible in her epic fantasy. Jimmy Chrismon, as the lively sib, and Patrick Hurley, in multiple cameos, provide superb support. Extra boosts come from John Hartness' lighting and Anthony Proctor's projection design.

Last Friday night, the universe was stood on its head at Supersonic, an oddly titled Charlotte Symphony Orchestra concert. Two guest artists, young conductor William Eddins and world-renowned clarinetist Richard Stoltzman, came in and performed a mostly 20th century program. And the Charlotte audience adored it!

The opener, Ralph Vaughan Williams' Fantasia on a Theme by Tallis (1910), delivered a foretaste of the sweetness and the razzle-dazzle to come. Built like a middle linebacker, Eddins strode onto the Belk Theater stage and cued the strings-only ensemble without a baton, conducting with only his beefy hands. It looked as if he'd brought a covey of guest musicians with him for, clustered behind the downstage strings, there was a little octet that replicated the main ensemble in miniature. As it turned out, these were all third-stringers plucked from the orchestra to form a separate antiphonal group.

A hushed, almost sacramental aura wafted softly through the hall as the piece began atmospherically. Cellos predominated as the theme crystallized, supplanted by the violins when the intensity notched upwards. Now the octet played against the orchestra before moving into the spotlight alone.

Fascinating, spiritual nourishment. Beautiful solos followed from within the main ensemble from violist Alice Kavadlo, concertmaster Jinny Leem, cellist Alan Black, and violinist Wolfgang Roth.

Fantasia ended as flawlessly as it began, shuttling between grand oceanic swells and hushed, churchly interludes that sounded like meditative organ music. See, modern classical compositions needn't be terrifying!

Next the CSO marched boldly into Handel's Music for the Royal Fireworks (1749) and nearly conquered. The overture unfolded impressively with the larger orchestra sounding looser and energized. Then a barrage of terrific brass, the trumpets sounding every bit as strong as the French horns. No, wait a second. The trumpets were sounding stronger -- steadier than the normally trusty horns.

That superiority carried over throughout the remainder of the five sections. It was as if the trumpets had been clamoring to play this music all through the McCoppin Era (the piece was last performed with Leo Driehuys in 1993), warming up with it at every rehearsal, while the French horns -- and the other winds -- had never seen the music before last Friday's performance. Luckily, after horns and winds had done their worst, the brass had the last triumphant word with powerful volleys of percussion.

With Stoltzman playing John Corigliano's Clarinet Concerto after intermission, many modernity-resistant subscribers discreetly sought the exits. Too bad for them. They missed an extraordinary 20-minute tutorial and demo prior to the performance, cooked up by Stoltzman and Eddins to sell the audience on the music. Since Stoltzman had to arrange a powwow with Corigliano to gain permission to play his concerto, you can say that he has an inside track to the inspiration and intent of the 1977 composition.

Stoltzman and Eddins obviously imparted the essence to the musicians as effectively as they did to the Charlotte audience. CSO accompanied spectacularly. Horns, clarinets, pocket trumpets, and percussion were deployed out in the rear of the house, all the way up to the rafters, for the concluding antiphonal toccata. Two conductors were required to execute this theatrical extravaganza -- David Tang sat mysteriously in the middle of the orchestra without an instrument until he suddenly rose majestically to summon the surround-sound fireworks.

Musically, most of the goodies -- and Stoltzman's choicest bravura -- occurred in the preceding two movements. Particularly touching were the forlorn flights of the elegy written for Corigliano's father, a longtime New York Philharmonic concertmaster. Here Stoltzman floated in over an eerie orchestral carpet, circled around CSO concertmaster Leem's ethereal solo in a symbolic father-son duet, and soared over the filigree of Bette Roth's harp.

This is where the pre-performance primer from Eddins and Stoltzman paid off most handsomely. Fear of modernity took a fearful beating at the Belk.

Many Carolinas Concert Association subscribers, young and old, may have entered Belk Theater unaware of the many achievements and honors racked up by the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra over the past 28 years, including three Grammys. But few of them left last Monday doubting or disputing their merit.

The compact 32-piece outfit, playing all night without a conductor, began with a refreshingly abrasive reading of Mozart's Symphony #25 that sounded very much like my favorite original instrument recording. Then they greeted their guests, The L.A. Guitar Quartet, and pounced on the piece these four personable virtuosi were born to play, Joaquin Rodrigo's Concerto Andaluz (1967). Outfitted with a magical adagio reminiscent of Rodrigo's famed Aranjuez, this concerto breaks irrepressibly into double time midway through the slow movement, subsides celestially, and then romps home amid flourishes of brass.

Smiling string players left the stage after intermission to the somber wind players, who lovingly caressed Dvorak's Serenade in D Minor. Along with the Rodrigo, that made two treasurable musical discoveries for the evening. Fine beginning for CCA's 72nd season, appropriately dedicated to the late Herman Blumenthal.*

Speaking of Arts_performance.html

-

Sailing With Hamlet

Jul 20, 2005 -

Proud To Be Plump

Jul 6, 2005 -

Putting The Sell In Cellulite

Jun 29, 2005 - More »

Latest in Performing Arts

More by Perry Tannenbaum

Calendar

-

RuPaul's Drag Race Werq The World Tour 2025 @ Ovens Auditorium

RuPaul's Drag Race Werq The World Tour 2025 @ Ovens Auditorium -

Boulet Brothers Dragula: Season 666 Tour @ N.C. Music Factory

Boulet Brothers Dragula: Season 666 Tour @ N.C. Music Factory -

Jim Norton @ The Underground

Jim Norton @ The Underground -

Trap & Paint + Music Bingo @ Blush CLT

-

Trap & Paint (Hookah Edition) @ Blush CLT

-

The Mind of Matt Cosper

XOXO Steps Beyond the Threshold of Freaky Theater

-

Jezebel star has Bette Davis eyes, nothing else 3

Play follows custom of casting male in lead role

-

Marriage and Divorce, American Style

Charlotte Rep's invitation to Dinner