Organizations Provide Help for Domestic Violence Victims and Abusers

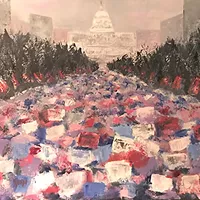

A city in need of sanctuary

By Ryan Pitkin @pitkin_ryanA text message Bea Coté recently received both inspired her and broke her heart.

She has experienced those emotions many times in the nearly 20 years she's worked in the domestic violence field. Coté is the founder and executive director of the Charlotte-based batterer intervention program IMPACT. When I caught up with her at a domestic violence conference in Uptown Charlotte on January 19, she was still thinking about the text she had received the previous night. It came from a woman named Dorothy, whose name has been changed to protect her. Coté met Dorothy four months ago, after Dorothy's husband nearly beat her to death using a Maglite flashlight.

Before the incident, in which Dorothy lapsed into a coma due to a traumatic brain injury, she had a good job at a local hospital. Since waking up, she has lived from one hotel room to the next, when she can get one, but has spent most of her time on the streets of Union County.

Dorothy's text, which we've edited for spelling and punctuation, gives a peek into the mind of a victim who refuses to give up:

"It's been hard for me to get anywhere, to do anything. Believe me, I'm more than ready to work and without a doubt know I can get work, it's the issue of staying warm and eating now," she typed to Coté. "This is why I say I'm at the complete end of my rope. I know what I am capable of. I right now, though, have to have genuine help; one chance ... Every trust and chance I have given people, I've been put further behind and further behind and right back to the beginning.

"I completely understand why the homeless stay homeless, and addicts stay addicts," Dorothy continued, "just like I understand why most women don't ever escape what I did and actually live a healthy, happy life after. But I have and I will, because I am hardheaded, lol. There's so many people I can help and so many I have come in contact with during this period that I have tried so desperately to help. I don't know how to help [myself] most days ... But I'm trying. I may not get anywhere, but I promise I will die trying to."

There are countless women like Dorothy in the greater Charlotte area — women who have lost it all due to domestic violence. And there are even more who are stuck in abusive relationships for fear of ending up on the streets if they were to leave.

In Mecklenburg County, only one shelter offers temporary housing for domestic violence victims and their children, and it remains full year-round.

Of all the services offered by the Charlotte-based domestic violence advocacy group Safe Alliance, including a victim assistance office and sexual trauma resource center, perhaps the most impactful has been the Clyde and Ethel Dickson Domestic Violence Shelter, opened five years ago this winter.

The shelter has 80 beds and houses 120 people, a large improvement over the 29 beds at the organization's former shelter.

Inside the shelter, the location of which is kept confidential to protect residents, a kitchen serves three hot meals a day to residents who live there for any amount of time, from a week to a year or even longer.

When Creative Loafing toured the shelter on a recent Sunday night, staff members at the entrance used cameras to identify anyone trying to enter the complex. Once inside, visitors have to identify themselves again to enter a gate, which gets them closer to a door. Once inside that door, visitors have to go through yet another door to enter a courtyard where kids run free and their parents can roam safely.

At around 6 p.m. at the shelter, kids chased each other down the hall after dinner, laughing. Down the hallway, rooms sat empty where residents would later meet for support groups, tutoring sessions and other types of meetings. A supply mart remained closed, but behind the door sat shelves stocked with diapers, menstrual items, school supplies and anything else residents might need from the free store that opens twice a week.

"We can never have enough baby wipes," said Tenille Banner, director of volunteer relations at Safe Alliance. "It kind of varies, depending on who's in shelter, what the main need is. We have a lot of children the same age at the shelter right now; lots of toddlers that are 1 to 2 years old. Some of them have been here for a few months, so at one point it was size-four diapers that we were constantly running out and couldn't keep enough of. Now they're up to size five."

That's an extremely important detail that affects the quality of life for a large chunk of the residents in the shelter, but it's just one of a countless list of responsibilities and specifics that Banner must be aware of day in and day out.

Banner began at Safe Alliance as a volunteer, then spent three and a half years on staff working with residents before moving into her current role recruiting volunteers and doing community outreach to raise awareness about domestic violence issues and the existence of Safe Alliance and the shelter.

She said recent events like the murder of Brittany White by her husband Jonathan Bennet, which Creative Loafing covered in part one of our series on domestic violence, have gotten people more interested in helping, but she hopes that level of engagement will remain as high as it is now.

"Times like this, when there's a story in the news, a high-profile incident, people want to know more so they start digging into it even more," Banner said. "But if you aren't the one affected personally and don't know someone close to you, it's very easy to forget that this is happening, but it is every day."

It's something that Banner can't forget, as she grimly pointed out while welcoming me to the shelter: Just because you're not seeing domestic violence on the news at any given time doesn't mean her workload has dropped off at all.

"We're so grateful to have this amazing space now," she said, with a smile, while opening one of the multiple gates leading to the residential hall. "But unfortunately, we're still always full."

Coté said she appreciates the work of those at the shelter, but she worries that not enough is being done around the city and surrounding counties for people like Dorothy.

"A lot of these victims don't go to shelters," Coté said. "Who is serving all these victims that don't go to shelters? There's a big, gaping hole."

At IMPACT, Coté works with abusers, many of whom are court-ordered to attend a batterer intervention program. Similar to the group sessions that staff members at the shelter mediate on a nightly basis with victims and children, Coté works for an hour and a half every week with each male abuser in her program, which lasts from 26 to 52 weeks.

In those groups, abusers discuss how their backgrounds play into their core beliefs and behavioral patterns, Coté said.

"What made them feel they were entitled to this behavior? We get them to recognize that there was a decision-making process in place, so then we give them the tools to replace that belief system and that entitlement with equality — with nonviolent, non-controlling behaviors," she said.

Coté has seen some of the more effective work done through IMPACT's legacy program, in which men who have gone through the program return and train to be facilitators. Their identification with other abusers works in much the way 12-step groups do, where alcoholics and addicts help each other stay clean and sober.

"There's nothing more helpful than having one of these legacy guys in the group," Coté said. "It's the thinking — they get it. They still have some of that thinking sometimes. So they're still doing their work, while helping the other guys along, and that's so much better than anything that I can do."

While Coté builds long-lasting relationships with some of the men who have passed through her program, she never loses sight of the people she does the work for — the victims. She contacts the victims of the abusers she works with, as long as they want to speak with her. That's how she met Dorothy.

"People don't understand. They say, 'You work with abusers,' and I say, 'Yeah, but it's because I'm working with their abusers,'" Coté said. "They call me, and they just want me to know either that he's not so bad, that he was once a loving guy, or they want me to know what a monster he is, because I'm working with him. So they want me to know these things, because my major job is to keep them safe."

Coté recently learned from one victim that a man had broken her finger while he was going through the program. Although he had already graduated from IMPACT by the time the victim told her, Coté reported the man and he is now facing charges related to the new assault and a violation of his probation.

Coté says many men do not finish the program, especially those who are not court-ordered to do so. That can be trying for her. However, she learned early in her career with the Mecklenburg County's Child Protective Services department that she won't make much progress dwelling on the negatives she encounters.

"I think I learned a long time ago that you've got to be appreciative and grateful of all the small, little, tiny successes," she said. "And that keeps me going."

For Banner, at Safe Alliance, a lifelong optimism has helped her continue her work in a field where so many victims fall back into the same cycles that they have suffered through in the past. She pointed out that it takes the average victim of domestic violence six to seven tries before they leave their abuser for good.

Until that happens, it's not Banner's job to pass judgment, she said.

"It can be trying at times, but that's with any profession," Banner said. "I can't speak for everyone, but me personally, I try to look on the bright side of things with a positive outlook, just really trying to understand our clients' perspective. In the time of getting an emergency protective order that lasts a few days, to having to go back to court again to make it a permanent one, they may have changed their mind and decided to give that person another chance. We just have to be understanding and supportive and be here for them if they decide later, 'OK, now I can't do this anymore.'"

What frustrates Banner is the victim-blaming she hears. People who haven't been in a similar situation often don't understand the psychological reasons why women don't leave abusive relationships, she said, and it hurts her to see people publicly shaming them for staying.

"There are lots of different reasons victims stay. So just understanding that cycle of abuse and how it works and how it traumatizes a person, that they have to rebuild their mindset and build themselves back up to know who they are again, that's important," Banner said. "We try to bring awareness to that, because victim-blaming is one of the biggest things we see — people putting it on them, that they could have just done a better job and got out."

An important part of Banner's job is to educate people, both young and old, about the cycle that victims of domestic violence can get stuck in, a cycle Creative Loafing will explore more deeply next week in the third installment of our series on domestic violence in the Charlotte area.

In the meantime, advocates like Coté and Banner will continue their work behind the scenes, whether or not the mainstream media continues to pay attention as recent high-profile incidents are replaced with other topics in the news cycle.

And true to form, Banner will remain optimistic.

"I see every day more and more people in the community reaching out," Banner said. "I see different groups that typically may not have been involved or as concerned about domestic violence wanting to learn and educate themselves more. I think the more we work to improve our legal system, that will make all the difference, as well, in people continuing to report more. We know one in four women are impacted by this and we know that's actually a greater number, because everybody's still not telling, but I'm definitely hopeful."

Speaking of...

-

Art With Heart Returns to its Roots

Feb 21, 2018 -

Advocates Work to End the Scourge of Domestic Violence in Charlotte

Jan 31, 2018 -

Crazy Times Require the Sanity of Women

Jan 24, 2018 - More »

Latest in News Feature

More by Ryan Pitkin

-

You're the Best... of Charlotte

Oct 27, 2018 -

Listen Up: Cuzo Key and FLLS Go 'Universal' on 'Local Vibes'

Oct 25, 2018 -

Listen Up: KANG is Back and Bla/Alt on 'Local Vibes'

Oct 18, 2018 - More »

Calendar

-

Cirque du Soleil: OVO @ Bojangles' Coliseum

Cirque du Soleil: OVO @ Bojangles' Coliseum -

Coveted Luxury Watches

-

TheDiscountCodes

-

Queen City R&B Festival & Day Party @ Blush CLT

-

R&B Music Bingo + Comedy Show @ Blush CLT